Company in the Archive

In a December 1, 2021 piece inThe New York Times about the new production of Company, Michael Paulson quotes Stephen Sondheim as saying “Marianne [Elliott] went and looked through all of George Furth’s early drafts to find out if something was useful, and she did.” Those drafts are preserved among his papers at The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, and it’s interesting to look back on them in light of the revised production.

As is well-documented in previous publications (including Harold Prince’s biography Sense of Occasion), Company began as a series of short plays by Furth without any plans to add songs. The plays were originally gathered under various titles, including “A Husband, A Wife, A Friend.”

This collection included a version of two scenes that appeared in Company: the Sarah and Harry scene (in which a man visits a couple who are both attempting to break unhealthy habits and who end up in a karate fight) and the Jenny and David scene (in which three friends smoke marijuana together).

A third scene, titled "Sally and Tim and Agnes and Gill," suggests the scene in the second act of Company in which Peter and Susan seem much happier as a divorced couple. In this early draft, one couple watches as another dances to music. The dance becomes increasingly erotic until the man carries the woman off stage. The woman who watched says to her partner, “They were right to get divorced.”

Finally, a scene titled “Peter and Georgia” ends with a conversation between two men who identify as straight discussing their occasional attraction to men and past homosexual experiences. Several lines from this scene were interpolated in the 1995 revival of the musical as a conversation between Peter and Bobby.

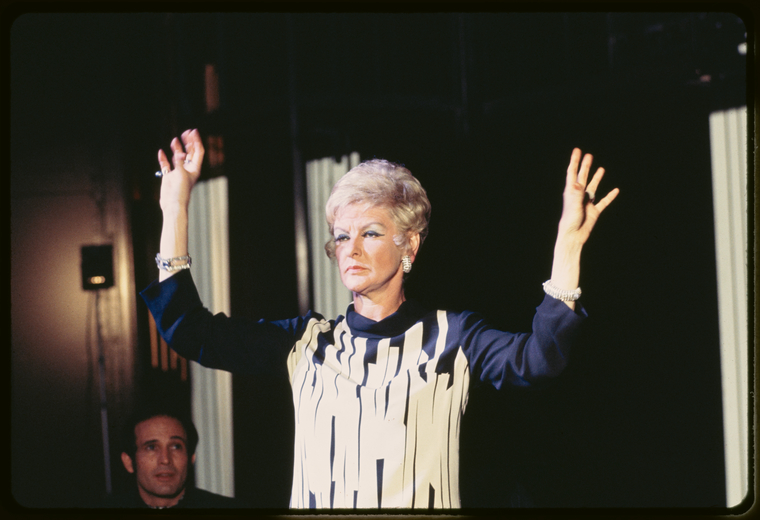

The most dramatic change in the new Broadway revival is, of course, the regendering of many of the characters, particularly Bobby/Bobbie. In Furth’s short plays, each character has the same gender as their successor in Company. However, Furth’s original idea was to have actor Kim Stanley play different female roles in each of the plays. Thus, the connecting tissue would not have been a single male character, but a single female performer. It would also have been something of a coup, as it would have marked the triumphant return of Stanley to the stage—she had not acted in a play since 1965, when she endured a particularly unfavorable response to her performance in The Three Sisters.

The production of Furth's short plays struggled to take off. Furth then shared his work with Stephen Sondheim, who in turn, shared it with Harold Prince. Furth recounts this story in a letter to his original producers, Porter VanZandt and Philip Mandelker. While he seems unsure about the prospect of adapting his plays into a musical, he does seem excited to implement his new idea: adding one consistent character to connect each play. (The “Gil” referred to in the letter is likely Gil Parker, Furth’s literary agent).

As Furth mentions, Kim Stanley had originally joined the project as the performer who would link the plays (albeit in different roles). In a letter of apology to Stanley, Furth tells her that he "owes [her] a play," but expresses excitement about the new direction the project has taken.

The project, of course, developed into one of the most critically acclaimed musicals of all time. And while Kim Stanley continued to work in film and television for decades afterward, she never appeared on stage again. If she could have peered into the future and watched the show at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, she may have been gratified to see a play not too far from George Furth’s original vision—and that there was room for a female lead after all.

Images used in this post from the Friedman-Abeles Collection have been preserved, cataloged, and digitized through the generosity of Nancy Abeles Marks and the Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.