Short-Term Research Fellows

Adapting and Commodifying Slavic Folklore in Russia and the West

Guest post by Jill Martiniuk who received her Ph.D. and M.A. in Slavic Languages and Literatures from the University of Virginia. As a Short-Term Research Fellow at the New York Public Library, she conducted research for her latest project on the adaptation and appropriation of Slavic folklore in contemporary young adult and popular literature in the West.

There has been an interest in reimagining and reinterpreting Slavic folklore in the Western young adult and popular literature markets for the past decade. From Catherynne M. Valente’s 2011 novel Deathless, which sets the tale of Marya Morevna in an imagined St. Petersburg during the Stalinist era, to Leigh Bardugo’s popular Shadow and Bone book series (2012-2021) turned Netflix show, these Western writers have relied on popular Slavic folklore motifs and characters to create fantasy worlds that have intrigued modern audiences. Some of these contemporary works have attracted a large fanbase online with websites and forums where readers try to make connections between the world of the novels and Russia.

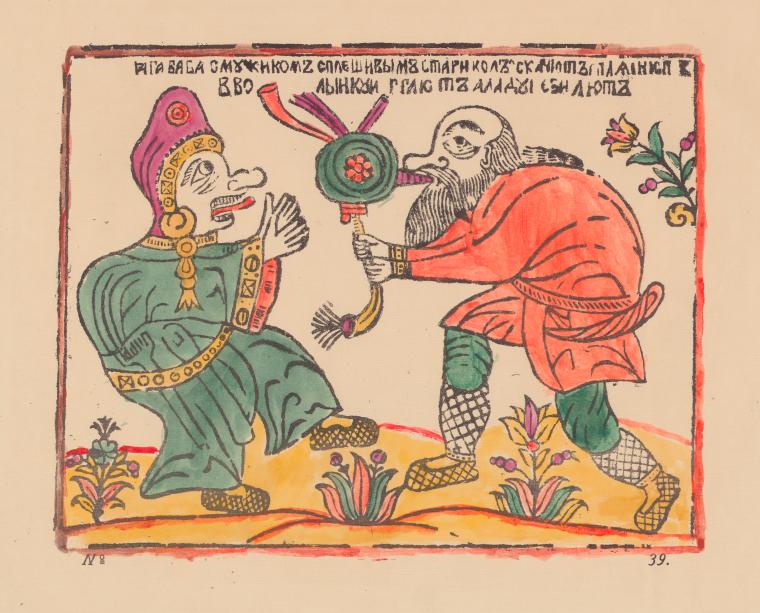

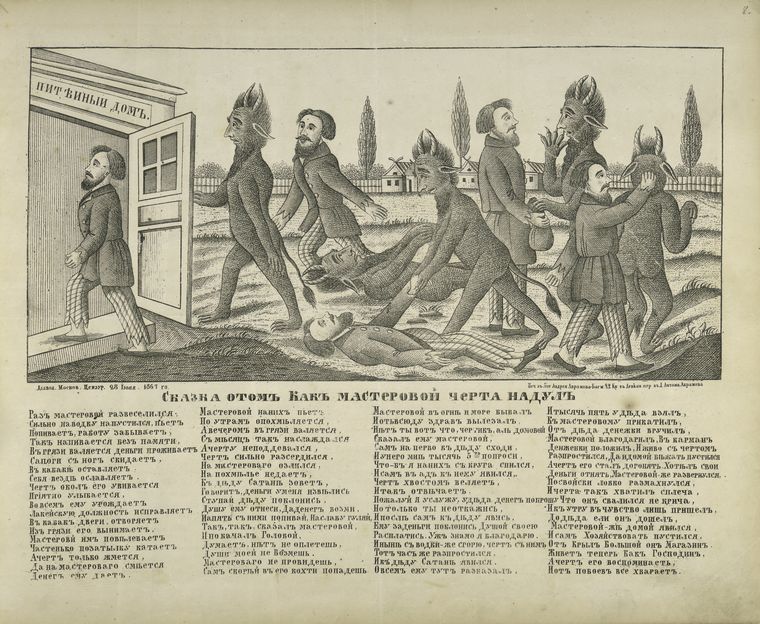

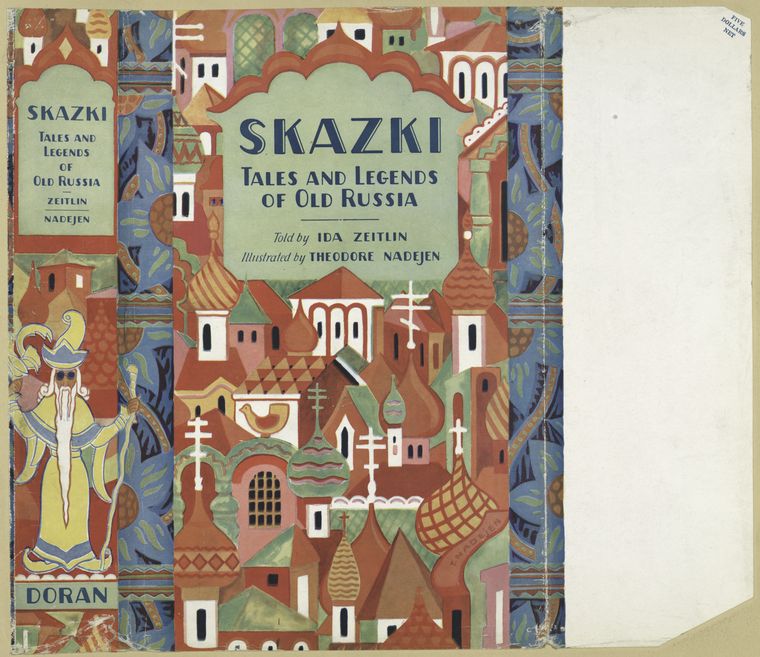

Yet to Russian speakers and Slavists, these works' folkloric characters and symbols don't quite resemble their predecessors. However, the fascination with Slavic folklore and co-opting it for another purpose is not new. The New York Public Library’s extensive collection of translations of Slavic folk and fairy tales shows a longstanding fascination with the genre in Russia and the West that the current young adult and popular markets are expanding upon.

Russian folklore has been a genre that has fascinated both academic and popular audiences for over a century. After hearing a particularly moving bylina, the folklorist and ethnographer Pavel Nikolayevich Rybnikov (1831-1885) wrote in his notes ("Zametka sobiratelia" in Pesni sobrannye P. N. Rybnikovym), “I was awakened by strange sounds: before that, I had heard many songs and spiritual verses, but I had not heard a tune like this one. Lively, whimsical, and merry, sometimes it got quicker. Sometimes it broke off. Its style was reminiscent of something ancient, forgotten by our generation. For a long time, I didn’t want to wake up and listen carefully to the individual words of the song: I was glad to remain the power of a completely new impression.” Rybnikov collected byliny from across Russia and published a four-volume collection of them. In the early 20th century, formalists like V.Ia. Propp’s Morfologiia skazki (The Morphology of Folktales) (1928) and A.P. Skaftymov’s Poetika i genezis bylin (Poetics and Genesis of Byliny) (1924) examined the structure to understand their form and function. Studying folklore became a way to take the songs and stories from their original community and popularize and then commodify them with a different audience through collections, translations, and studies.

Although the golden age of collecting and studying folklore came to an end by the late 1920s, the Soviet government, thanks in no small part to the efforts of the writer Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), saw that folklore could be a “significant factor in the formation of the socialist culture” because of its themes and focus on heroic labor. Rather than relying on the old songs and stories, Soviet officials decided to take the structure and themes of byliny and modernize them to create heroic epics about workers. This new genre was dubbed noviny, and like their predecessor, reflected a heroic ethos and showed characteristics associated with greatness and strength. The form used familiar themes and devices in folklore but served a new ideological agenda. Some byliny singers, like Marfa Semyonovna Kryukova (1876-1954), who came up with the term novina, transitioned from singing the traditional folk songs to the noviny. They toured the Soviet Union singing the pseudo-folkloric songs about laborers and workers and received support from the state. Although the noviny enjoyed popularity for some time, ultimately, they had no lasting power and fell away during the Zhdanov period. However, they show how folklore can be commodified within the confines of the country of its creation and how it can be repackaged and repurposed as a genre.

The recent popularity of young adult and contemporary novels set a folkloric version of Russia (or imagined land heavily influenced by Russia) extends the appropriation and repackaging of Russian folklore. In these modern works, familiar characters take on modern traits and new identities just as they did in the noviny. In Valente’s Deathless, Baba Yaga is now Chairman Yaga, a gruff party member who trades in favors and secrets, while in Katherine Arden's The Winternight Trilogy, Morozko, the frost king, has become a brooding romantic lead. The success of these books, their subsequent turns into duologies and trilogies, as well as offers of movie and streaming deals, shows another way that Russian folklore has been commodified.

Both noviny and the current Western trend of adapting Slavic folklore for a typically younger and more modern audience show folklore as something that can be assigned value and profited from by an outside audience. In the Soviet Union, folklore served an ideological purpose. Its familiar structure and themes could be repurposed and modernized to advance the goals of the new state.

Exploring how byliny and other forms of folk culture have been co-opted and reimagined within Russia and beyond its borders gives us more context to understand why modern and Western audiences have done the same. The NYPL’s Slavic collection offers Slavists and folklorists the opportunity to see all the ways that folklore has been adapted and appropriated.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.