Teaching American History With NYPL Digital Collections: Childhood in America

Everything has a history, even (or, especially!) the most personal and seemingly timeless parts of our lives. Teaching students about the history of childhood—a phase of life that they may be in the midst of or have recently experienced—allows them to think critically about their own lives and their place in history. Understanding that they, as young people, are historical actors and that their lives are worthy of scholarly analysis can be a profoundly empowering experience.

Happily, The New York Public Library has all of the resources instructors need to teach students about the history of childhood in America: primary sources, historical monographs, online tools, and much more.

In this guide, as in past ones, I’ve put together a curated group of documentary resources that can be tailored to many different levels and classrooms, from middle and high school social studies classes to undergraduate and graduate courses. Individual documents from NYPL’s Digital Collections provide excellent materials that can be used to excite the imaginations of students and teach them document analysis. More advanced students can pursue independent research projects using many of NYPL’s e-resources, as well as digitized materials available via NYPL’s archives and manuscripts portal. Along the way, I’ll also share tried-and-true teaching resources from other institutions.

The History of Childhood in America: The Basics

Think for a moment about common and often-unquestioned ideas about childhood today. Children are meant to be nurtured and beloved. Children thrive in environments of play and discovery. Parents are responsible for caring for and molding children into adults. Children are vulnerable and innocent, in need of protection from the vicissitudes of the world.

This vision of childhood is not an eternal one, but instead sprung from the particular historical moment we live in now.

If we look back over the centuries, childhood has served strikingly different social roles and has reflected often contradictory cultural values. From the perspective of 17th-century Puritans, children were not innocents but vessels of sin. In the 19th century, the youngest members of families were essential and hardworking laborers. Ideas about education, parenting, and play have all emerged as a result of changing social and political beliefs at different moments in history.

For an excellent overview on these changing historical understandings of childhood, one that offers both rich detail and synthetic narrative, teachers should start with Steve Mintz’s beautifully written Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood, available as an e-book with a valid NYPL library card (Patrons can log in and search for the book using the title). This monograph also works as a reading for undergraduate and graduate students. High school teachers could assign Mintz’s introduction.

The below proposed exercises address both experiences and representations of children in different eras of American history. An important note for instructors teaching content-heavy surveys, including high school and undergraduate courses: the history of childhood does not have to be an additional or standalone lesson in an already-crowded US history syllabus. The topic can be incorporated into many other units in American history, from the Progressive Era to studies of modern media.

Teaching Topic #1: Depictions of Working Children

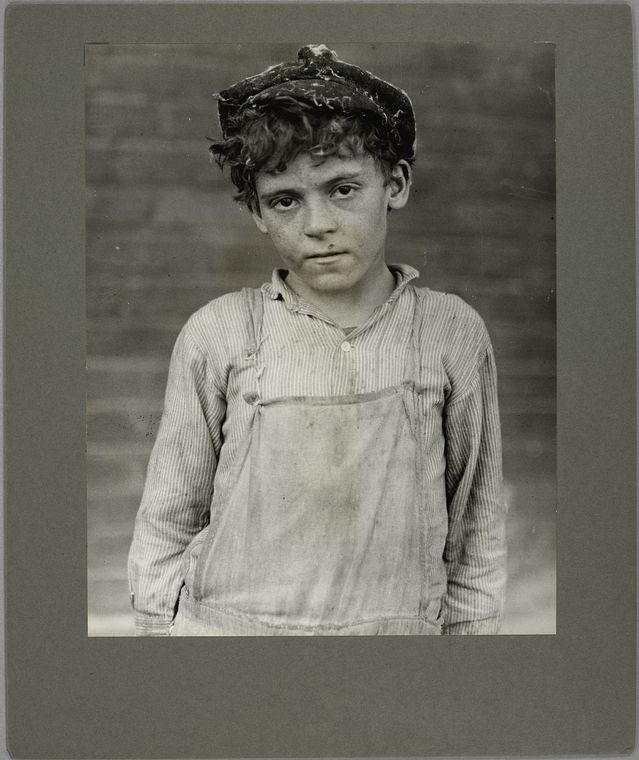

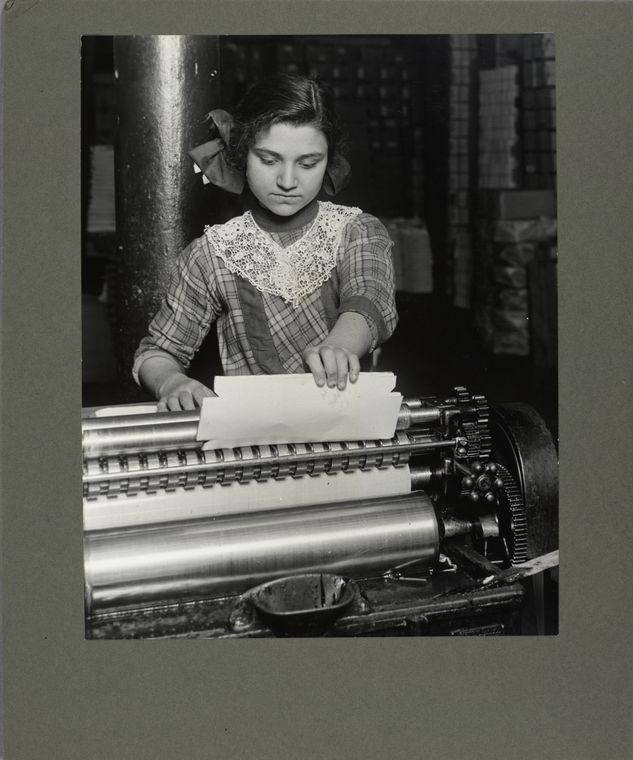

Sometimes, it can be jarring for students to learn that for most of American history, children were a significant part of the economy and workforce, and that they often labored in grueling and dangerous conditions, especially during the height of the country’s industrial development. During the Progressive era, reformers began to push for the regulation and elimination of child labor, documenting young workers’ lives and experiences. Many of those images are available on The New York Public Library’s Digital Collections.

Before diving into primary source analysis, teachers may want to provide students with essential context about child labor. Consider assigning this engaging American Social History Project podcast episode,which brings together historians and activists and ties the historical issues of child labor to conditions today.

Next, instructors and students can explore a series of images of children at work, taken by Progressive-era photographer and activist Lewis Wickes Hine. (The Zinn Education Project, one of my favorite teaching resources, has an excellent guide that provides teaching models and context on Hines and his work.)

NYPL’s Digital Collections include hundreds of photographs by Hine, many of which depict children laborers. Instructors may choose to pick a small collection of complimentary or contrasting images, such as these:

I chose these images because they depict children of different genders, ages, and geographical regions (but not different races; Hines rarely photographed African American children). Ask students to consider both the content of the images and the perspective that Hine has imbued. Your prompts might include the following:

- From these images, what can we learn about the kind of work children did in the early 20th century?

- What observations can you make about the environments in which these children are photographed?

- Compare how these children are portrayed. What similarities and differences can you notice?

- What does Hine want the viewer to think about these children and the work they do? Who do you think Hine’s intended audience was?

- Using the images and the titles of the photographs, what observations can you make about the race or ethnicity of these children? Hine rarely photographed African American children. Can you make any conjectures about why?

Instructors looking to extend this lesson can craft a follow-up assignment using additional NYPL e-resources. For example, ask students to use Proquest American Periodicals, accessible with your NYPL library card, to locate articles about child labor during the same years Hines took these photographs. Can students find articles or opinion pieces that articulate different sides of the child labor debate?

Teaching Topic #2: African American Children’s Literature

One of the most challenging—and potentially groundbreaking—aspects of teaching the history of childhood is crafting lessons that push students to interrogate the powerful but unexamined influences that shape our understandings of race, class, and gender. A great example of this is children’s literature. In parables about good and evil, right and wrong, innocence and corruption, children’s books have historically prioritized narratives about white children, referenced sometimes shocking racial and ethnic stereotypes, and left unquestioned the racial and gender hierarchies that have defined American society over the centuries.

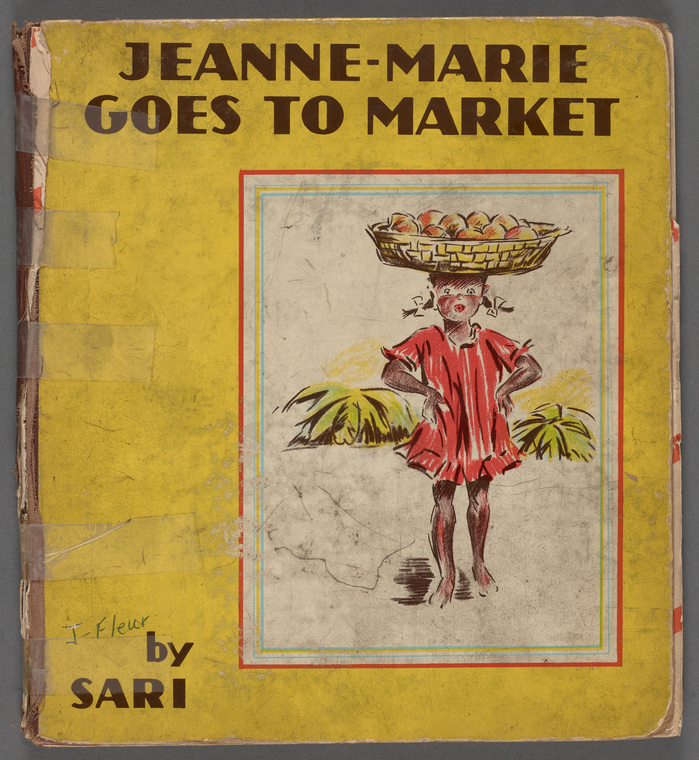

Racism in historical children’s literature is sometimes overt, using racial epithets and reducing nonwhite characters to caricature . Sometimes that racism is more subtle, hidden under the surface in beloved classics like A Cat in the Hat (check out this talk by author Phillip Nel unpacking the meanings of Seuss’s most famous character).

While understanding the racism embedded in children’s literature is essential, this lesson focuses on historical interventions in the canon of children’s literature made by pioneering African American authors, scholars, and professionals.

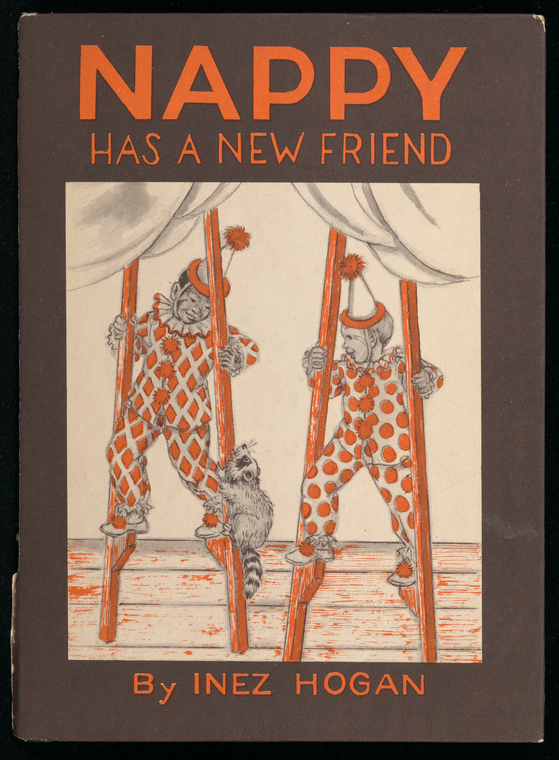

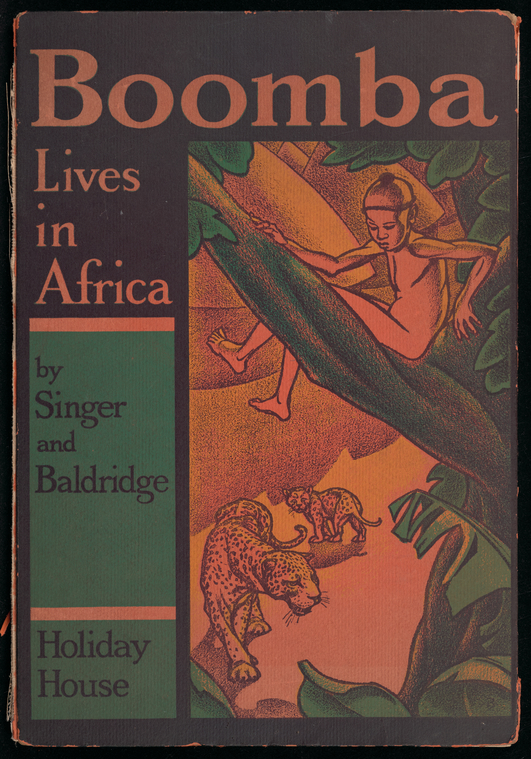

NYPL’s Digital Collections include a rich collection of children’s books that reflect the black experience in America and beyond. Compiled by longtime NYPL librarian Augusta Baker, these books sought to provide accurate and multilayered depictions of the lives of black children during a time when racism in children’s literature went unquestioned.

At NYPL, Baker devoted her career to building collections of anti-racist children's books, promoting children's literature, and working closely with authors from Madeleine L’Engle to Ezra Jack Keats. For context on Baker's important work, students can read the short introduction to her seminal bibliography, The Black Experience in Children’s Books, available via NYPL Digital Collections.

To provide students a framework for analyzing the children’s books in the Baker collection, consider assigning Chapter Two, “Scriptive Things,” from Robin Bernstein’s Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights, available as an e-book with your NYPL library card.

Now it’s time to dig into the children’s books in the Baker collection. Instructors in more advanced courses can ask students to explore the collection themselves and select two books to analyze using Bernstein’s framework. For students with less experience with independent research, teachers should select a book or two and do a page-by-page analysis as a group exercise.

I like the idea of focusing on books with slightly different messages, interventions, or intended age groups. For example, books like Laugh With Larry or Nappy Has a New Friend offer depictions of interracial friendships without comment on the protagonists’ races. Other books like Boomba Lives in Africa focus on black children and offer narratives about Africa that aren't imbued with racist colonial stereotypes. Still others like Julie’s Heritage are intended for a tween or teen audience and tackle more complex issues of race, class, and social acceptance.

Teachers looking to expand this analysis exercise into a broader project can ask students to research how these books were received by mainstream publications. Students can select a book from the Baker collection and use Proquest American Periodicals or Newspapers.com to locate contemporary reviews of these books.

Teaching Topic #3: Analyzing Parenting Advice

As experiences and depictions of childhood have transformed drastically over time, so has advice on how to raise children. In the 20th century, newspaper advice columns became essential places to disseminate new ideas on how to properly parent.

While in the 19th century, most child rearing advice focused on mothering, in the 20th century, modern culture ushered in a new interest in the role of fathers in the lives of their offspring. A key figure in this new vision of fatherhood was a writer and educator named Angelo Patri. Patri authored a popular syndicated advice column called “Our Children,” which offered accessible guidance about child psychology for an audience of millions. Patri emphasized the essential role that hands-on fathers played in the development of their children, and featured many letters from fathers seeking counsel. Readable and easy to search and access, his columns are great primary sources for teaching.

For context and analysis on Patri’s approach to fatherhood, check out Ralph LaRossa’s The Modernization of Fatherhood: A Social and Political History, which includes a chapter on Patri and his impact on collective understandings of fatherhood.

Teachers and students can access Patri’s columns using NYPL’s digital newspaper collections, including Newspapers.com, America’s Historical Newspapers from Readex, and Proquest Historical Newspapers. Depending on the grade level and research proficiency of the class, teachers can ask students to locate and analyze a small group of columns on their own (hint: search "Our Children" AND Patri AND father), or they can select columns ahead of time and provide them to students. Newspapers.com has a Clipping tool that allows instructors to create PDFs of articles for simple dissemination.

We’d love to hear how teachers adapted these lessons and employed NYPL collections in their classrooms! Please comment on this post with stories and other ideas.

More Teaching American History with NYPL Digital Collections:

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.