Masks Are the New Mittens

The recent spate of online instructions for make-it-yourself masks are part of an honorable American tradition: in times of crisis, private citizens—especially women—have always been quick to step up and supply front-line responders with what the government can’t, or won’t, provide.

A remarkably similar case in point occurred during the Civil War. When government-issued gloves proved insufficient—in type and number—to keep the soldiers’ fingers warm, newspapers and journals published instructions and patterns for mittens that were eagerly followed by female knitters across the divided country.

Just as at present, the effectiveness of these individual efforts varied, and it became clear to many that a more coordinated approach was needed, especially to distribute all of the individually-produced supplies. To meet this need, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States, formed the Women's Central Association of Relief (“WCAR”) in New York City in April, 1861. Local chapters of the WCAR sprang up around the country, systematically collecting and distributing life-saving supplies such as bandages, blankets, food, clothing and medical supplies—as well as, of course, mittens.

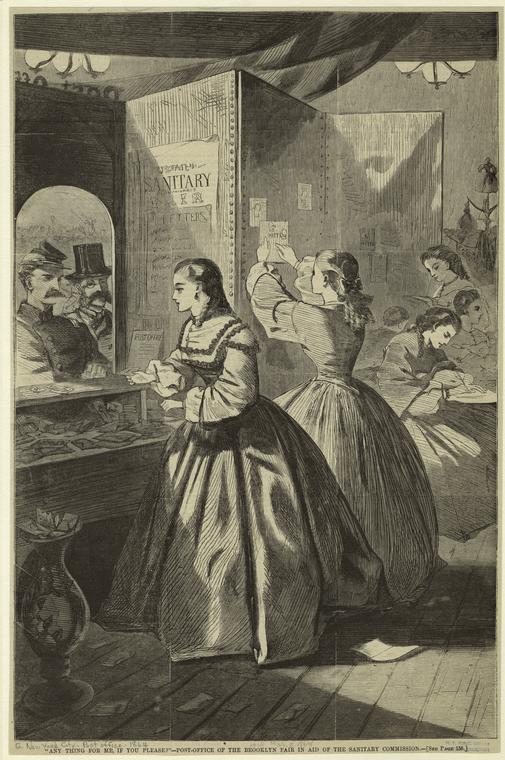

From this nucleus, the United States Sanitary Commission came into being. This too-often-overlooked organization was created as a private relief agency through federal legislation signed on June 18, 1861. Although headed by men—including executive secretary Frederick Law Olmstead—its work was performed primarily by unpaid volunteer women. In addition to making mittens, socks and other needed supplies themselves, women volunteers held bazaars and organized Sanitary Fairs to raise money for additional medical equipment (including what passed for Personal Protective Equipment at the time) and countless other supplies and services. It’s estimated that the U.S. Sanitary Commission raised $5 million in cash and $15,000,000 worth of supplies during the Civil War.

Could your female ancestors have been a part of this volunteer force? To explore this possibility, consult our new guide How to Find Your Suffragette Ancestors, freely available to all at home. It includes information and resources relating to women's aid societies during the Civil War, including the U.S. Sanitary Commission (see specifically the pages Mapping the Suffrage Movement and How to Learn More). Although not directly tied to the suffrage movement, the aid soceities organized by women helped pave their way to a broader role in post-Civil War society, and instilled in many women volunteers the confidence and experience to move outside the domestic realm.

One of the U.S. Sanitary Commission’s primary objectives was the prevention of diseases among soldiers—a goal that resonates deeply as we try to support each other during our own health crisis. When the Library building re-opens, researchers will once again be able to access the U.S. Sanitary Commision records, held by NYPL's Archives and Manuscript Division.

In the meantime, make sure you wear your masks—and when you do, remember that they reflect a long tradition of private efforts to protect the public’s health.

Sources and Further Reading

- Giesberg, Judith Ann (2000). Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women's Politics in Transition, Boston : Northeastern University Press.

- Scott, Ann Firor (1991). Natural Allies: Women's Associations in American History, Urbana: University of Illinois Press

- How can we best help our camps and hospitals? Statement and correspondence pub. by order of the Woman's Central Association of Relief, New York. New York : Wm. C. Bryant & Co., printers, 1863 (available online through HathiTrust)

- Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women: Autobiographical Sketches by Elizabeth Blackwell, Hastings : K. Barry, 1895 (London : Spottiswoode and Co.) (available online through HathiTrust)

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.