Made at NYPL, Paperless Research

Frontier Feminist Miriam Michelson: An Interview with Lori Harrison-Kahan

The Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library holds the Century Company records, with the majority of the collection donated by the company in 1931. The Century Company published the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, widely regarded as the best general periodical of its time, performing a role as cultural arbiter during the 1880s and 1890s. Founded in New York City in 1881, the Century Company also published the children's magazine St. Nicholas, dictionaries, and books.

The Library chose to digitize the records in their entirety—correspondence with readers and contributors, administrative records, manuscripts, and proofs. Beginning in 2016, the collection was reassessed and described anew by archivist Amelia Carlin, photographed by the Library’s Digital Imaging Unit, and placed in the Library’s Digital Collections with the assistance of the Metadata Services Unit. The collection is now fully available for online research.

One such scholar taking advantage of this expanded access, Lori Harrison-Kahan is an associate professor of the practice of English at Boston College. She edits and introduces the collection The Superwoman and Other Writings by Miriam Michelson, which provides a look at the "girl reporter," magazine writer, and novelist through a compilation of her work in the early 20th century. Intertwined with Michelson’s work is the passage of suffrage in her home of California and then nationally, and the changing demographics of American citizens. In this conversation, Harrison-Kahan discusses her study of Michelson, and how the digitized Century Company records aided in her work.

To begin, who is Miriam Michelson, and what first drew you to her as a subject?

Harrison-Kahan: A bestselling novelist in the early 20th century, Miriam Michelson started her career as one of the first female journalists in San Francisco in the mid-1890s. Later, she leveraged her fame as a popular writer and celebrity reporter to become a suffrage activist. I was drawn to Michelson because of the way she used various forms of print culture—the daily newspaper, popular magazines like Century and The Saturday Evening Post, as well as novels—to make a case for gender equality and to empower women.

I was also intrigued by the fact that Michelson was famous in her own time, and yet has been overlooked in literary and historical scholarship. When I tell people my book is on Miriam Michelson, I get blank stares, even from scholars in my field. Hopefully, The Superwoman and Other Writings will change that and get people thinking about why she has been overlooked for so long.

Which do you find most interesting, Michelson’s newspaper writing or fiction writing?

Harrison-Kahan: I love the novella The Superwoman, which is why I chose it is as the title story of the collection. It is about a utopian society in which gender roles are reversed and women are in power. The story is quite funny at times, but it makes a powerful political point.

Overall, though, it is her journalism that I find endlessly fascinating, especially because she uses the first person and makes herself a character in the stories. We think about news reporting today in terms of objectivity, but that was not the case when Michelson wrote. Women journalists in particular became part of the news stories they were covering—it was news that a woman was reporting in the first place!

I’m also intrigued by the way her journalism has both historical and literary value. It’s interesting stylistically, but also offers a new lens on history. For example, when she covers the debate over the annexation of Hawaii in 1897, she makes a concerted effort to include the perspective of native Hawaiian women and show that they oppose being annexed by the United States. This was a viewpoint that is not always covered in high school American history courses.

It’s even more fascinating to put her journalism and fiction into conversation with each other, which was my goal in publishing this collection. The experience of reading The Superwoman and Other Writings is intended to be interactive, allowing readers to see how Michelson used her journalism as source material for her fiction, and how she borrowed techniques from fiction to make her journalism entertaining. In her journalism, she created a distinct voice and persona. Later, in her novel A Yellow Journalist, she created a fictional character based on herself, a "girl reporter" in the age of Hearst and Pulitzer.

You studied recently digitized Century Company records materials from NYPL. How was the experience of accessing them online rather than in a library?

Harrison-Kahan: I love spending time in libraries and archives, and working with original documents. But the travel involved to do on-site research can be a challenge since it requires funding and finding time amidst teaching to make trips to various locations. In the case of Michelson, most of her papers were not saved—in part because she was a single woman without direct descendants and because the work of women writers was often seen as unimportant for posterity. As a result, there was no single archive that I could visit to help me piece together her story. Instead, I found bits and pieces of archival material in libraries around the country, from California to Indiana to Massachusetts and, of course, New York.

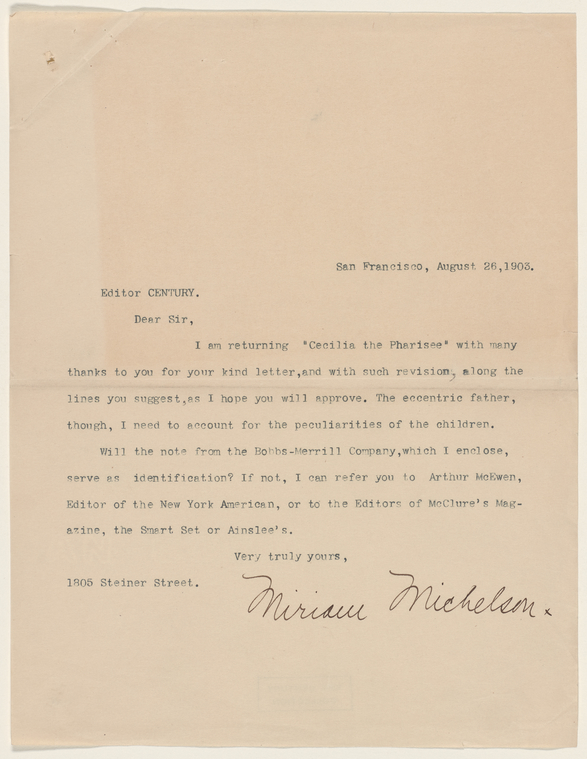

I knew that Michelson had published stories in the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine and that her second book, an autobiographical novel called The Madigans, was published by Century Company in 1904. The digitized letters were an incredible boon for my research.

I was sad not to have an excuse to visit The New York Public Library in person after having the pleasure of doing research there for my first book. But I am glad to have the digital option, which definitely made my research more efficient.

How did the Century Company records' editorial correspondence figure into your understanding of Michelson?

Harrison-Kahan: Most of Michelson’s correspondence with Century took place over a brief period of time, between 1903 and 1905. This was a crucial period in Michelson’s career as a writer because she was in the process of shifting from journalism to fiction. In 1904, the Bobbs-Merrill Company published her first book, In the Bishop’s Carriage, which evolved from a short story she published about a female thief in Ainslee’s the year before. The novel was a scandalous sensation and became the basis for a play and two films. The story’s heroine, Nance Olden, was an icon of modern femininity, a prototype for the 1920s flapper.

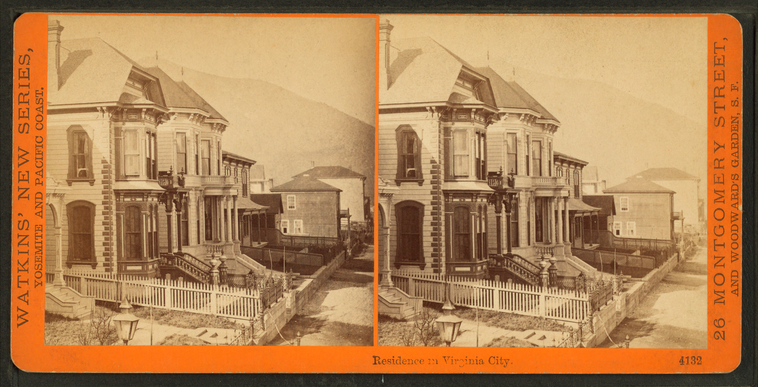

Michelson’s business with Century followed quickly on her success with her first novel. The magazine first published a series of short stories about a family of six sisters growing up in Virginia City, Nevada, Michelson’s hometown.

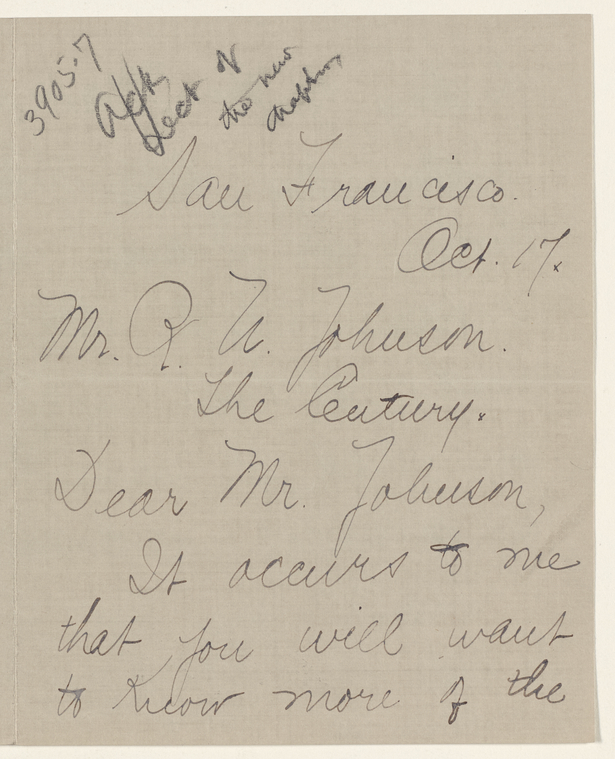

The stories were based on Michelson’s childhood adventures and were close to her heart as a result. This comes across in her letters. She is clearly having fun writing the stories—and wants her audience to have fun reading them, too. At the same time, she takes small details seriously.

In one case, a story contains a reference to a distinct Virginia City landmark, Bob Graves’s Castle, a mansion built in 1868 by engineer Robert Graves after he became a millionaire thanks to the mining boom. The editor suggested that Michelson refer to the residence as "the best house" instead of by the specific name, but Michelson objected. Her objection shows her fidelity to place and to the experience of childhood. She notes in the letter that a child growing up in a small town would naturally refer to a house "by its first name." Michelson never had children of her own and, at one point in a letter, refers to her characters, the Madigan girls, as her children. No wonder she lavished so much attention on seemingly small details!

Michelson’s correspondence with Century editors offers invaluable insight into her personality. Most writers, of course, have a different style on the published page than they do in correspondence. Michelson's style in journalism and fiction is often bold and sassy. In her correspondence, in contrast, she is sometimes self-deprecating.

For example, at one point, she thanks the editor for his "interest in my little Madigans," which is not simply a reference to the age of the characters; it also conveys her humility about her work. In letters with her editors at Bobbs-Merrill, Michelson sometimes expressed surprise at continuing to receive royalties for In the Bishop’s Carriage. She didn’t expect her work to be as popular as it was. She was pleased by her success but did not take it for granted.

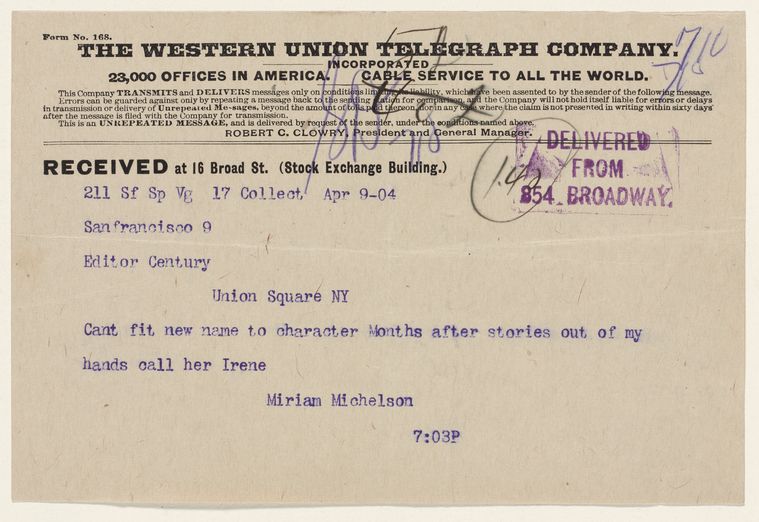

There is another seemingly small detail from the Century correspondence that struck me and told me so much about Michelson as a person and a writer. In The Madigans, she has the sisters refer to each other by their nicknames. The nicknames are meant to get across the characters’ personalities; they are tomboys and can’t be bothered with the propriety of formal, feminine names. Michelson gave the character of Irene the nickname "Split" in reference to her athletic ability. The editor objected, seeing it as "vulgar" and "suggestive." Michelson disagreed. Although the magazine changed Irene’s nickname to "Sprint" when the story was serialized, Michelson made sure to switch it back to "Split" for the book version. She wanted to maintain artistic authority over her own writing. In this sense, she is like her characters, who are strong women and know what they want, especially out of their careers.

What strikes me about the set is the difficulty of conducting business via post. The first documents are to prove Michelson's identity!

Harrison-Kahan: Yes, Michelson was living in San Francisco and the Century Company was based in New York, so it took some time for letters to cross the country. In addition to the letters, she also sent telegrams, which helped speed up the process.

For scholars doing historical research, there is a real advantage to the old-fashioned postal system. In contrast to electronic communication today, the correspondence creates such a rich, multi-layered historical record. For example, envelopes, stationery, and letterhead all provide important clues, including about where Michelson lived and traveled at various times. Plus, it’s always exciting to see an author’s signature and handwriting. Michelson’s handwriting was, thankfully, pretty good. I didn’t have to spend a lot of time puzzling out words, as I do with other writers’ handwritten correspondence.

It’s very interesting that Michelson had to prove her identity to the Century Company since, at the time she began her correspondence with them, she was already a celebrity reporter in San Francisco. But newspaper reporters had local followings, which is often still the case for journalists. Michelson may have turned to fiction because she was seeking a larger audience for her work; she could find a home for her fiction in popular, mass-circulation magazines like Century, which had a national subscription base.

There is another clue in the Century correspondence, which suggests a motivation for Michelson turning from journalism to fiction. In introducing herself to the Century editor, she says that she left journalism for fiction because she was "reformed." Newspaper work, especially in the era of sensational journalism, was not exactly seen as a respectable profession, especially for a woman. She was definitely a trailblazer.

What aspects of Michelson’s work will resonate with contemporary students or scholars?

Harrison-Kahan: As I was working on this book, her work, written over 100 years ago, suddenly became more relevant as the current feminist movement took new shape. She wrote about professional women, gender and power, and sexual harassment in the workplace long before #MeToo. And she did it in a breezy, engaging, often comic style that makes her writing entertaining to read.

One of the most exciting parts of working on this project was seeing how Michelson’s work resonated with students. I’ve taught Michelson’s work in my classes, and I had a number of undergraduate research assistants who helped me with the book. (Shout out and thank you to Marena Cole, Marianna Sorensen, Grace Denny, Karen Choi, Maggie McQuade, and Sophia Pandelidis.) I knew I was on to something important with Michelson when my research assistants told me how much they were enjoying going through reels and reels of old microfilm, and how thrilling it was to discover a new article by her, bleary eyes aside. Michelson’s work resonated with them for the same reasons it resonated with me. It feels surprisingly contemporary.

In the field of American literature, where there is increasing attention to periodical studies, scholars will be interested in the ways that Michelson mobilized print culture. At the current moment, the nation is observing the centennial of the 19th Amendment, and Michelson was a proponent of the suffrage cause, and active in California’s campaign to get women the vote. The collection has a lot to tell us about the way women made their voices heard in print, and the ways that journalism and fiction functioned as women’s primary means of democratic participation before 1920. It’s an apt time for this collection to appear. I’m hopeful that other scholars will undertake further research on Michelson and make use of the NYPL digital collections in the process.

In addition to the Century Company records, the Library holds the papers of editors Richard Watson Gilder and Robert Underwood Johnson. Contact manuscripts@nypl.org to coordinate access.

Has your work benefited from The New York Public Library collections? We’d like to hear about it! Submit news of your exhibition, book, thesis, article, art work—anything—to www.nypl.org/citationtracker

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.