Manhattan Mistabulation: The Story of the 1890 New York City Police Census

The 1890 Federal Census

The federal census conducted in 1890 was notable for at least two milestones in the history of the United States, and one consequential misfortune. Census results showed the open range of the wild west had been finally and fully canvassed, settled, identified, bought up, surveyed, or mapped. "Four centuries from the discovery of America…" wrote Frederick Jackson Turner, "the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history." The end of the frontier also marked a beginning in data technology, as the 1890 federal census was tabulated by an early form of the modern computer. According to the Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census, "for the first time in census history, the work of tabulating census results was carried out by automatic tabulating machinery."

Though plentiful statistical data was extracted from the 1890 census, the hundreds of thousands of pages of population schedules were damaged in a 1921 fire in the basement of the Commerce Building in Washington, D.C. The charred pages were salvaged and placed in storage. Then, as Prologue Magazine writes, "in December 1932… the Chief Clerk of the Bureau of Census sent the Librarian of Congress a list of papers no longer necessary for current business and scheduled for destruction... Item 22 on the list for Bureau of the Census read 'Schedules, Population ... 1890, Original.' The Librarian identified no records as permanent, the list was sent forward, and Congress authorized destruction on February 21, 1933."

Like the frontier, the 1890 census was gone for good. As a result, researchers of the gaslight era must turn to the handful of resources available as alternatives to the 1890 federal census—for example, New Jersey state censuses conducted in 1885 and 1895, or U.S. city directories published in 1890. For New York City, and Manhattan in particular, researchers can check the 1890 census conducted by the New York City Police Department. Though it featured fewer columns of data than its federal counterpart, the 1890 police census remains a highly useful resource in NYC genealogical pursuits.

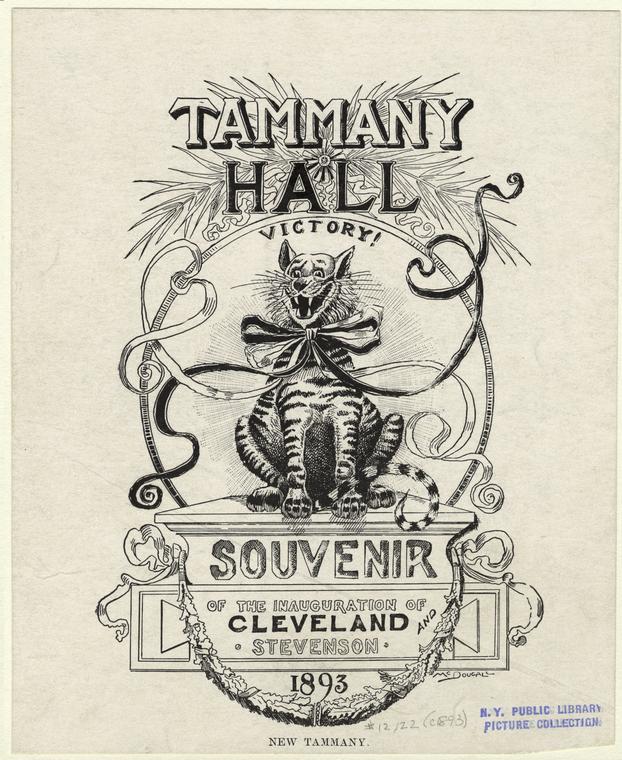

New York's Finest in 1890 did not carry out a local enumeration just so that, 125 years later, genealogists in the Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History, and Genealogy at NYPL could locate their great-great grandmother living on Cannon Street. The origins of the 1890 police census involve the history of disputed U.S. census returns, Tammany Hall politics, and the rabid brinksmanship of congressional reapportionment.

Apportionment

The U.S. federal census is a government effort to count, or "enumerate," every inhabitant of the 50 states and Puerto Rico, and features detailed accompanying household data. Census results were—and still are, in preparation for the 2020 census—important to every municipality in the United States that receives money from the federal government, while the chief purpose of federal population statistics is to apportion representation in Congress and state legislatures.

For an example of the wide-ranging and highly consequential political effects of congressional apportionment, consider the dominance of slave-owning U.S. states before the Civil War. The enslaved population of the U.S. was about four million by 1860, and each of these individuals was forbidden to vote. Nonetheless, enslaved household members were tallied for congressional apportionment as three-fifths a human being. This calculation, concocted by the authors of the Constitution, was then used to support the population numbers required by states to apportion seats in Congress.

As a result, slave states gained an average of 20 more congressmen after each decennial census than they would have had using only the free population for apportionment, in addition to 30 more electoral votes. The entire enslaved population of Virginia surpassed the number of free African Americans in the entire United States in 1860. The enslaved populations of Mississippi and South Carolina outnumbered the free population of each of those states by tens of thousands. These population results—enslaved and free—were tallied by the federal census.

These antebellum census numbers deliberately exploit the misrepresentation of the actual population; the more typical pattern in the history of the federal census follows a legacy of misrepresentation by undercounting the population.

The very first census was conducted in 1790 under the direction of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who was suspicious of the accuracy of the initial returns. Taken by 650 federal marshals over 18 months, the census numbers showed a population count of 3.9 million, while Jefferson estimated that "making very small allowance for omissions which we know to have been very great, we are certainly above 4 millions, probably about 4,100,000."

One of the biggest civic fits thrown in response to U.S. census returns occurred in 1890, when Democratic Mayor Hugh Grant disputed the population numbers received for the Big Apple. Parsing results published in September by Superintendent of the Census Robert Porter, Mayor Grant roused constituents into a state of disbelief that 12 Manhattan wards had inexplicably decreased in population by over 40,000 since 1880.

Compounding the statistical dissonance, the total population fell short of NYC Health Department estimates by at least 84,000 people. The numbers might have implied a heavy spike in the death rate, but Mayor Grant declared "I do not believe that New York is the unhealthy place that these figures make it out to be."

Reenumeration

Local politics in the 1890s was dominated by district leaders aligned with Tammany Hall, the "machine" of local Democrats whose engines were fueled by political favors, and whose cogs and wheels were greased by graft and bribery. As described in Tigers of Tammany:

"At the bottom of the Tammany power structure is the voter who depends on the party to care for his needs. He, in turn, confers power on the party through his obedience at the polls. The block captain knows the individual voter and his problems and gives him his personal attention. In the name of the party, he asks only for allegiance in the form of a vote. The block captain is subordinate to the Election District captain who administers a larger unit and maintains control by apportioning favors that are passed to him from the next higher level, the Assembly District leader. The leaders of the Assembly Districts… comprise the Executive Committee which selects the County Leader. But once the supreme Boss is chosen, he assumes absolute authority over those who have chosen him."

The NYC Board of Aldermen, dominated by Tammany members, warned that "grave injustice is done to the city in many respects, and especially in substantial injury and wrong likely to occur through the deprivation of just Congressional representation by an apportionment based on such defective census."

The Board resolved to apply "to the President of the United States, the Secretary of the Interior and the Superintendent of the United States Census to order a recount of the population of the City of New York in order that the inaccuracies of the enumeration which has been had may be corrected." A second enumeration would not have been unprecedented: two enumerations had occurred in 1870 when New York City officials threw a tantrum over weak population returns, and the second showed a two percent increase of New Yorkers.

The 1890 Police Census

Meanwhile, Mayor Grant approved the deployment of the New York Police Department to conduct its own enumeration of the 24 Assembly Districts of New York City, which included sections of the Bronx from Kingsbridge to the South Bronx, west of the Bronx River. The Manhattan police census, conducted in October, counted 1,710,715 inhabitants—about 200,000 more than the federal count of 1,515,301.

Some of the population increase was likely due to New Yorkers originally out-of-town in the hot month of June or, who in some way, either missed or avoided enumeration. But it was also alleged that cops routinely counted men at home and then again at their workplace, and counted out-of-towners visiting the city. In addition, given the reputation of Tammany Hall politicking, it was no stretch that district leaders were said to have promised favors to enumerators in return for padding the census count.

City newspapers took sides on the issue. The New York Times ran an editorial referring to the federal census as "so untrustworthy as to be almost completely worthless," while, down the block on Nassau Street, the New York Tribune countered snidely that the police census was a "partisan enumeration," and that Mayor Grant was simply giving voice to the cigar-and-beefsteak stratagems of Tammany Hall Democrats, to expand their power in newly created political districts.

When early returns for the police census showed substantial increases over the federal count, the Tribune explained "that is the reason why you see so many smiling Tammany heads of departments around City Hall nowadays." The Tribune was against a recount and editorialized in support of the federal census returns. "Not an atom of proof has been offered to show that the enumeration of the population of the United States as a whole has not been honestly made in accordance with the law."

The Times published articles that demonstrated the civic necessity of a recount, like data cited by the president of the New York City Board of Health in support of reenumeration, and the Building Bureau noting the increase in Manhattan construction as evidence of a population spike.

The Tribune did not disagree the population may have been undercounted but reasoned that, in June, when the federal census was taken, many people would have left the sweltering and unsanitary city, versus October, when the police census was taken, and the city was naturally more populated. The discrepancy in numbers was also derived from newly arrived immigrants between June and October, estimated to be 125,000; that year, an average of 38,000 residence-seekers arrived at U.S. ports per month, with increased numbers in the summer months when maritime traffic was heavier, and a majority of incoming passengers landed at the port of New York.

No Recount

Once the police census returns were added up, Mayor Grant avowed "it would be a neglect of my duty were I to fail again to protest against the treatment of New York by the Federal authorities and the State Legislature." The police census showed a gain of 200,000 people in the city’s population; however that "representation has thus far been denied" by the federal government. Grant conceded "I have no power to do more than has been done to redress this grievous wrong."

In December 1890, Congress passed an Apportionment Bill, which increased the members of the House to 356 beginning March 3, 1893. Before the final vote was taken, arguments were made over the permission of a recount in New York City. Republicans, outnumbering Democrats, all voted against a recount and all Democrats but one voted in favor. The sole donkey siding with the elephants was George Tillman of South Carolina, an ex-Confederate soldier who espoused increasing the House to 600 members, providing greater representation to citizens of the south and west, and returning the income tax to American law.

The Times referred to the NYC recount refusal as an "injustice." But ultimately, after all the snarky op-ed pieces by Park Row newsmen and splenetic speechifying by Tammany heelers, and for all the paranoia about the loss of seats in the House, the results of the 1890 federal census effected no gains or losses in Congress for the state of New York.

The federal enumeration of 1,515,301 would be used as the official number for congressional apportionment, with the police census results failing to spur the Department of Interior to initiate a second enumeration. "A partisan census is an impossibility," wrote Superintendent Porter, because it is "not the work of one man" but "the united labor of not far short of 60,000 men and women." Porter ridiculed the sophomoric conspiracy theories of the "reckless demagogues" of Tammany Hall, "who judge the actions of others from the standpoint of their own moral capacity and mental incapacity."

Porter was aware of the inherent margins of error, since "we are all liable to pitch our key too high in talking of the marvelous progress of the nation." But his revulsion at party shenanigans made him even more steadfast in sticking to his original numbers.

In typical fashion, New York City flaunted its gargantuan ego with hypersensitivity. "A person might be led to believe," wrote the Tribune, "if he read only one or two Tammany newspapers, that the whole country is in a ferment over the census returns in the city of New York."

Echoes of such "ferment" still resound in New York City's response to federal census results. This year, when the Census Bureau estimated NYC had dropped in population by 40,000 since 2017, Mayor DeBlasio countered that "what we see with our own eyes appears to be the real truth—that our population has been steadily growing."

Using a more local idiom, Mayor Bloomberg addressed the likely inaccuracies for Queens in the 2010 enumeration: "borough-wide, the Census Bureau determined that the population of Queens increased by only 1,300 people during the past decade. That's an increase of just one-tenth of one percent. Could that really be possible? As they say in Brooklyn: Fuhgeddaboudit."

Postscript: 1898

The partisan bickering and biased pontifications about control of the state legislature may appear, from some angles, as simply political arrogance and type-A patriarchal greed. This is not an unfair judgment nor inaccurate. However, the 1890 police census inspired the state legislature to finally conduct a new state census in 1892, incurring more accusations of fraudulent enumerations puppeteered by Tammany Democrats. The backlash put Republicans—the upstate party—back into power, where they would remain to dominate both the Assembly and State Senate well into the 20th century.

Between 1892, when Democrats controlled the New York State governorship and legislature, and 1897, when Republican Governor Frank Black signed the Greater New York Charter—which consolidated the city of Brooklyn and the township of Queens with Manhattan, Staten Island, and a part of the Bronx to form the city of New York—the identity of the city shifted as it had not since Evacuation Day in 1783, when the British Army was driven from the island, and NYC commenced to freely evolve over the decades of the Early Republic.

Consolidation, which would have been a much more glacial process under boss politics of local Democrats, created what Mike Wallace and Edwin G. Burrows describe in Gotham as a city "over three million strong, over three hundred square miles, larger than Paris, gaining on London," and "ready to face the twentieth century." It was the end of the 1890s, and a "colossus had been born."

For tips on using the 1890 New York City police census for research, see our Guide to Researching the 1890 NYC Police Census. If you have any research questions, be sure to reach out to the Milstein Division at history@nypl.org.

Bibliography

- Margo Anderson. Who Counts? The Politics of Census-Taking in Contemporary America

- Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham (New York, 1999)

- Encyclopedia of the Antebellum South

- Encyclopedia of New York State, "Legislature"

- Encyclopedia of the U.S. Census

- “The Eleventh Census,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (Nov 15, 1890)

- August 29, 1791, "Letter to William Short," The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 22

- Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States (1860)

- J. McPherson, “Southern Comfort,” New York Review of Books, April 12, 2001

- “Census Increases Still Booming,” New York Herald (October 9, 1890)

- “That Unreliable Census,” New York Times (September 18, 1890)

- “For the New Census,” New York Times (September 21, 1890)

- “The New Census,” New York Times (September 23, 1890)

- “The New Apportionment,” New York Times (December 18, 1890)

- “To Recount New Yorkers,” New York Tribune (September 16, 1890)

- “The Partisan Enumeration,” New York Tribune (October 15, 1890)

- “New York City’s Census,” New York Tribune (November 29, 1890)

- Proceedings of the Board of Aldermen, Volume 199, September 2, 1890

- Proceedings of the Board of Aldermen, Volume 201 (January 5, 1891 – March 31, 1891)

- Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History

- Department of Homeland Security, 2017 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.