In the Weeds: The History of Botanical Illustration and the Work of Anna Atkins

When William Henry Harvey published A Manual of the British Algae: Containing Generic and Specific Descriptions of all the Known British Species of Sea-weeds, and of Confervae, both Marine and Fresh-water, it contained 229 pages of text and no pictures. In the book's introduction, Harvey noted he had wanted to include some form of illustration, but "my limited stay in Europe did not afford time to prepare them, and it does not now appear desirable to delay the publication ‘til they could be got ready."

Harvey’s dilemma was not unique. For centuries, writers, printers, and scientists grappled with how to efficiently and accurately illustrate their works. Then, in Renaissance Europe, the invention of the printing press spurred a proliferation of the printed word, and renewed interest in the sciences. Combined, these factors led to an increased need for accurate and efficiently reproducible images, and existing illustration methods fell short in a variety of ways.

The Challenges of Botanical Illustration

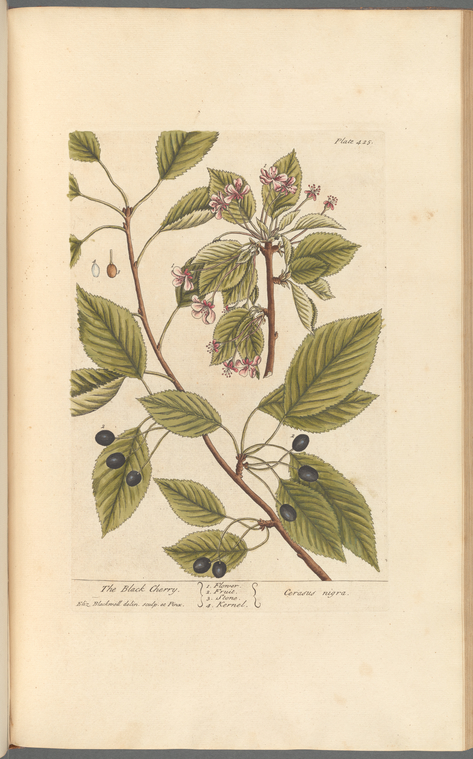

Hand-drawn illustrations posed a number of limitations. Drawings were expensive and time-consuming to produce, requiring the artist to complete hundreds or thousands of examples for each publication. Further, the hand of the artist and the eye of the scientist were not always in agreement, resulting in visually pleasing images with debatable scientific merit. For those focused on flora, this challenge was only compounded by the common practice of artists generating illustrations based on other artists’ interpretations rather than actual plant specimens, leading to repeated and sometimes emphasized inaccuracies.

Some sought to resolve this issue by using actual dried plant specimens as illustrations. The inclusion of an actual plant certainly had advantages: readers could observe texture, thickness, structural characteristics, and other physical aspects lost through two-dimensional illustration, and the specimens could even be observed under a microscope. However, collecting enough quality examples for each individual copy of a book was incredibly labor-intensive and time-consuming, replicating many of the issues present in other illustration methods. Dried specimens also became fragile and would break down or suffer damage over time, and could present preservation challenges.

Printing processes were more efficiently and reliably reproduced than manual drawings, but the method replicated many of the same complications. Printing ensured consistency among individual copies, but problems with accuracy remained as the plates and blocks were created from hand-drawn images. Producing hundreds or thousands of images was surely more efficient than drawing them all by hand, but the process still required an exorbitant amount of time and money, and many works went unpublished due to a lack of funding. Many publications attempted to reconcile this challenge by severely restricting the number of illustrations, with authors and publishers often selecting a mere handful out of hundreds or thousands of plants discussed in the text.

Nature printing, a technique in which an actual specimen is used to either create a plate for repeated printing, or to apply ink directly from the plant to the page, existed in Europe in some form at least as far back as the 15th century, and possibly earlier. Coating a plant with ink and pressing it to the page yielded images with detailed representations of veins, stems, and other textural details. Unfortunately, this process also had flaws: images lacked realistic, nuanced color and were flattened, disproportionately emphasizing and distorting certain features. And, like other methods, printing each image individually would have been a laborious process, and printing directly from plants would have required collecting (and destroying) many specimens.

![[Wild Fennel] by William Henry Fox Talbot, ca. 1841 [Wild Fennel] by William Henry Fox Talbot, ca. 1841](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/talbot_wild_fennel.jpg)

The Use of Photograms

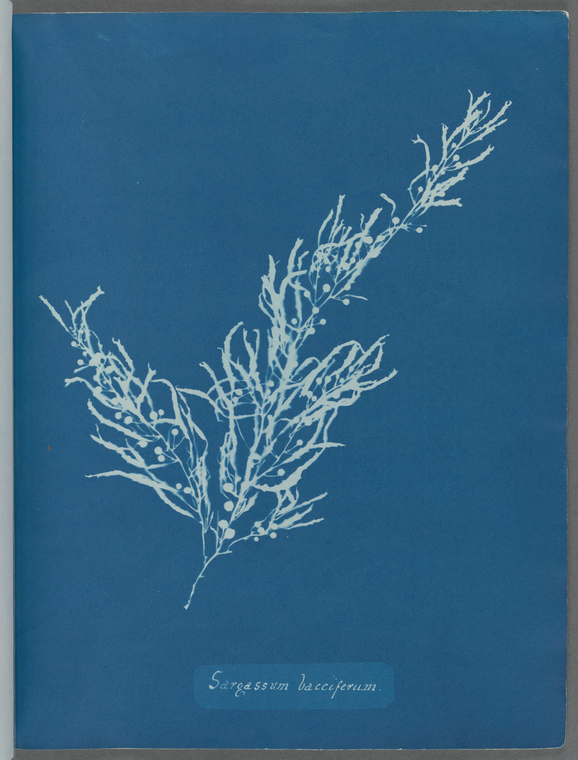

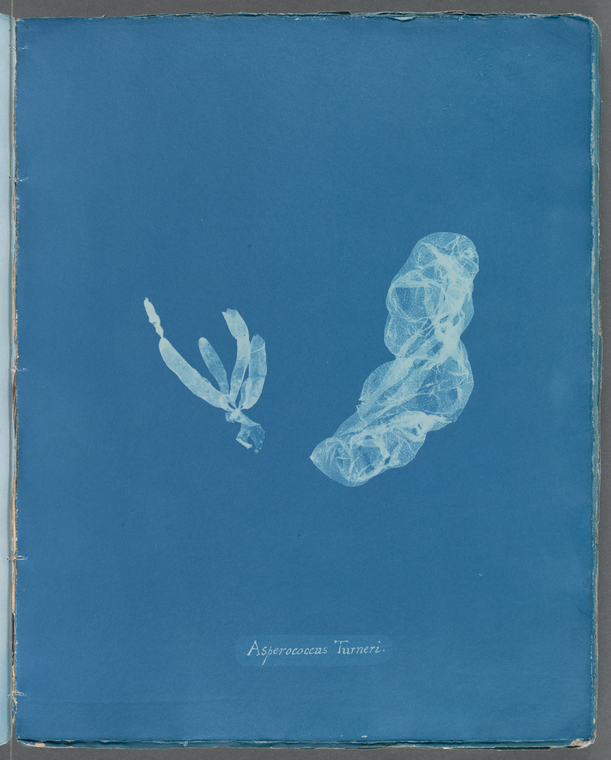

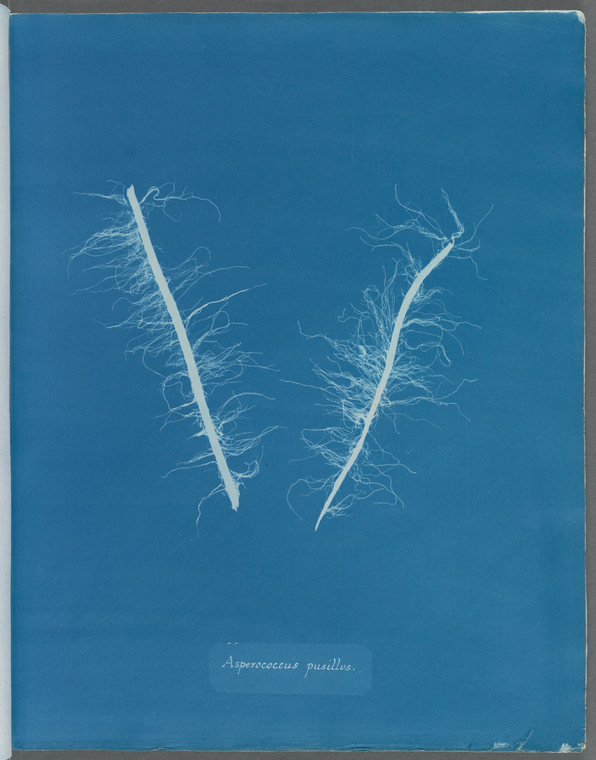

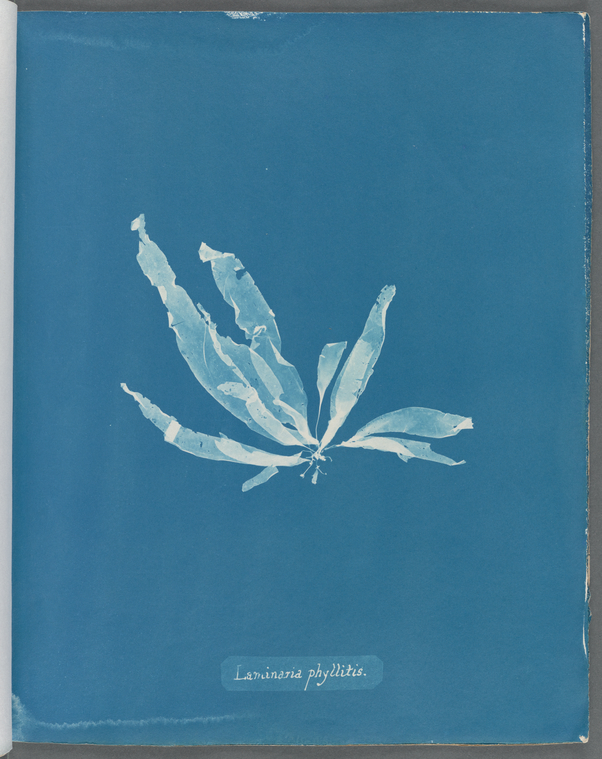

From the beginning, photograms and plants were a natural pairing. William Henry Fox Talbot’s earliest photosensitive papers required an object be placed on top to create a negative image. Being readily available, plants were an advantageous subject, and the cyanotype’s ability to feature variations in translucency and detail made it seem like a potential solution to the problems burdening botanical illustration.

Further, only one example of each plant was needed to create multiple plates, and the specimen would remain intact throughout production.

As groundbreaking as Anna Atkins’s Photographs of British Algae was, the cyanotype was not the great problem-solver. The cyanotype’s attractive blue color suited the subject of marine algae, but did not show color beyond its varying blue and off-white tones, and may have seemed an odd pairing for terrestrial plants. The process of producing each plate by hand—treating the paper, waiting for it to dry, creating the negative, and then fixing each image and waiting again for the sheets to dry—did little to reduce production time. Ultimately, the images are of debatable value to botanists in identifying plants and algae in the wild.

Although Atkins’s masterwork ultimately made virtually no impact on scientific illustration, Photographs of British Algae is a groundbreaking achievement in the context of bibliographic and photographic history. By producing thousands of cyanotype photograms by hand, and then painstakingly hand sewing them into parts, and then volumes, Atkins is known today for having produced the first photographically illustrated book—a legacy that resonates beyond one single discipline.

Discover more about Anna Atkins and her work in "Celebrating the Life & Legacy of Anna Atkins."

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.