A Dancer's Life, Shaped by Jerome Robbins by Ellen Bar

Ellen Bar trained at the School of American Ballet, joined New York City Ballet as a member of the Corps de Ballet in 1998 and was promoted to Soloist in 2006. While dancing, Ellen developed and produced the narrative dance film NY EXPORT: OPUS JAZZ, which premiered at the 2010 SXSW Film Festival and aired on the PBS series Great Performances.

In this blog post, Ellen recalls her first encounter with Jerome Robbins' work at age seven with her mother, a Soviet-era ballerina, and her changing relationship with his works as she becomes a professional dancer, then a filmmaker, and finally a mother herself.

When I was 7 years old, my mother took me to see New York City Ballet for the first time. It was an all-Robbins program: Dances at a Gathering and something else I can’t recall. It’s an odd choice for a child’s first ballet but, then again, the choice wasn’t about me. My mother is a former dancer from the Soviet Union and the evening was meant to be a rare treat for her. My parents had emigrated to the United States ten years prior, and they’d only recently begun to permit themselves small luxuries.

We sat in the fourth ring, where the dancers were distant and tiny. I remember examining the program, enjoying the simplicity of the character names—Brown, Pink, Yellow, after the color of their costumes—which made sense to my seven-year-old brain. I spent the first few minutes happily connecting the figures on the stage to the characters in the program, trying to remember from my Crayola box what color was "brick." Solo followed solo, duet followed duet, and it all began to look the same. Every now and then, someone did a long balance, or a dizzying amount of turns, and I perked up. But mostly it was just dance after dance after dance, set to a gentle piano score. I was bored. So instead of watching the stage, I watched my mother.

Like most former ballerinas, my mother was not easily impressed—she had been brought up in the proud Russian tradition, trained by Vaganova’s own students. At home, I was always treated to a running commentary of criticism when we watched ballet videos. But at the theater, she’d completely forgotten I was there, absorbed in what was happening on stage. She sat perfectly straight with that unmistakable dancer’s posture, leaning as far forward as she could without falling, literally on the edge of her seat. Every now and then she let out a rapturous sigh or a little laugh, clapping vigorously in between dances.

I was fascinated by her reaction and frustrated too—because whatever it was that was so remarkable to her was invisible to me. I knew that I was missing something, that this ballet contained some profound truth that I couldn’t grasp. I filed it away with all the other mysteries I planned to solve once I was grown up.

Eight years later, having followed in my mother’s footsteps, I was an advanced student at the School of American Ballet, living in the dormitories across the plaza from the New York State Theater. During the winter season, New York City Ballet performed every night for weeks on end. If there were any vacant seats, the house manager sometimes let in a few students. The house manager’s name was Mr. Kelley, and he was a forbidding-looking man, with colorless eyes and a brusque manner. Every night, the students would ask him about tickets, and every night he’d turn them away—"nothing for you," he’d say, waving us off.

The faint-of-heart would leave, but not me, and not my close circle of friends. We stayed and stayed, as the last bells rang, sometimes even after the orchestra had begun. We learned to play up our disappointment, to plead and beg and moan, and Mr Kelley’s cool facade would crack. "Alright," he’d say with a little bit of grudging respect, as he wrote us a pass for the last row of the orchestra. I remember how magical and powerful those passes felt, like keys to the kingdom, though they were just little white cards with the seat numbers hastily scribbled on.

This was how I saw Dances at a Gathering, I mean, really saw it, for the first time. The music and the choreography which had been white noise when I was younger suddenly emerged as a language I could understand. Not just a language, but poetry; satisfying on the surface for its rhythm and melody, but also rich with a deeper meaning. Like my mother all those years before, I sat on the edge of my seat, relishing the nuance of small gestures, the unexpected musicality, the way the movement personified joy. The dancers were there only for each other, a community united by a common passion. They were me and my friends, navigating art, friendship, rivalry, and love on a daily basis, our relationships continually forming, shifting, breaking. This is where my own love affair with the Robbins works began. For the rest of my time as a student, I made sure not to miss a single Robbins ballet—with Mr. Kelley’s help, of course.

During those student years, I often saw Jerry (I took the liberty of calling him that in my head) in the audience and I dreamt of telling him what his work meant to me. Time and again, I circled him, shark-like, at intermissions, but either the right moment never presented itself or I was too scared to seize it when it did. I doubt my compliment would have meant much—he’d received far more important ones than mine. Then again, no one understood the vulnerability of adolescence better than Jerry.

I joined New York City Ballet as a corps member in 1998, just two months before Jerome Robbins died. I got to know his ballets in a new way, from the inside out, by dancing them. When choreography feels right, when it embodies the music perfectly, when it becomes ingrained in your muscle memory, it brings you closer to the creator. Dancing Robbins’ ballets in the Company where he created them was enough of a gift for me. But Robbins would continue to give in ways I could never have predicted.

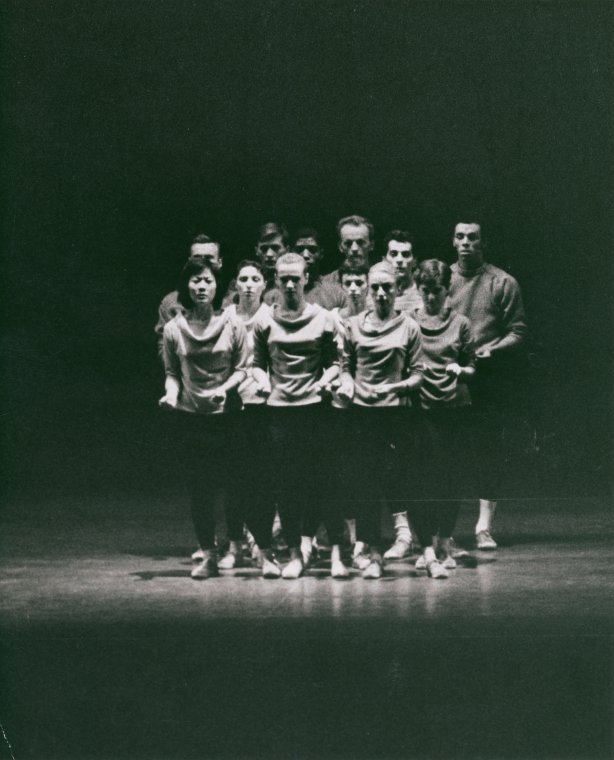

In 2005, I was part of the original cast of New York City Ballet’s revival of NY Export: Opus Jazz, which had not been performed in decades. I was just one of the ensemble, yet it was one of the most satisfying experiences of my dancing life. Just like Dances at a Gathering, I found my youthful struggles, my deep connection to my city, my complicated relationships with my friends inside the dance. And I saw something else too—I saw how this particular ballet, which in so many ways was a product of the late 1950s, could be updated for a new era without losing its essential nature.

Along with my fellow soloist and best friend, Sean Suozzi, I developed an idea to reimagine NY Export: Opus Jazz as a film, shot on location in present-day New York City, with scripted narrative scenes to weave the different movements together. During his life, Robbins rarely allowed anyone to alter his work in any way. To protect his legacy after his death, he left strict requirements about how his ballets should be rehearsed and performed. Naturally, the Robbins Rights Trust was wary when we approached them. But, inexperienced filmmakers that we were, we made clear that it was Robbins himself who had planted the seeds of our project. The fact that we could envision NY Export: Opus Jazz as a film was only possible because of what Robbins had done with West Side Story, shooting dance in a visceral, cinematic way at gritty, urban locations. And despite his own inexperience directing major motion pictures, he won an Oscar for his very first one. He showed us what was possible, even if it was improbable.

Five years later, with a lot of help, hard work, and more than a little luck, NY Export: Opus Jazz aired on PBS, bringing what was once a little-seen ballet to millions of people around the country. It went on to play film festivals and arthouse cinemas, and was broadcast on foreign television networks around the world. Together with the Robbins Trust, we created a curriculum to accompany the film, which has been used across the New York City public school system. Because of NY Export: Opus Jazz, I found a new career as a film producer after I retired from dancing. And I met my future husband, Jody Lee Lipes, who co-directed and shot the film.

Last month, we sat beside our three-year-old daughter at a children’s program at New York City Ballet. Like all the other doting parents, we watched her more than we watched the stage, finding joy in her joy, as she bounced in her seat to Fancy Free and West Side Story Suite. For now, she loves the sailor costumes and all that snapping but, someday, she will see so much more. When that day comes, I’ll tell her all about Jerome Robbins, and how he changed the shape of our lives, starting with Dances at a Gathering all those years ago.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.