Jerome Robbins at 100, and After, by Julia Foulkes

Julia Foulkes is the curator of the exhibit Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York, opening on September 26. Her book, A Place For Us, discusses the historic placement of the stage musical and film West Side Story in New York City during a time of urban renewal. It also frames the musical in the American and global landscape, transcending feelings of mistrust during the Cold War through its universal themes.

Jerome Robbins saved everything. Or so it seems. The Jerome Robbins Dance Division holds a voluminous amount of his correspondence, notes, contracts, bills, diaries, sketches, paintings, awards, photographs, and film footage that record an extraordinary life of expression and accomplishment. When invited to mount an exhibition in honor of the 100th anniversary of Robbins’ birth, on October 11, 1918, I was thrilled—and dismayed. Where to begin? What might help me choose items for display from so many possibilities?

A specific theme helped. The exhibition examines Robbins’ relationship with New York, his home and his muse. The city served as a laboratory for Robbins, where he observed people, buildings, traffic—how movement in space could carry meaning and beauty. His keen attentiveness to the world around him came through in acute staged portrayals of the city ranging from the Broadway and Hollywood hit West Side Story to the ballet Glass Pieces. Showcasing creative works with ties to New York was an obvious goal.

Beyond artworks to feature, though, I was eager to formulate principles that might also guide me in knitting together a long, prolific, and complicated life. I started with the assumption that although Robbins is a superstar in dance, many people might not know him at all. He died 20 years ago and choreographers are less likely to be remembered than composers or actors. Leonard Bernstein, for instance—also 100 this year—has far wider name recognition even though some of Bernstein’s greatest hits were created in collaboration with Robbins, such as Fancy Free and West Side Story. The challenge would be to introduce people to Robbins who might not know him and also show other sides to him for those who may have known him or his choreographic work well.

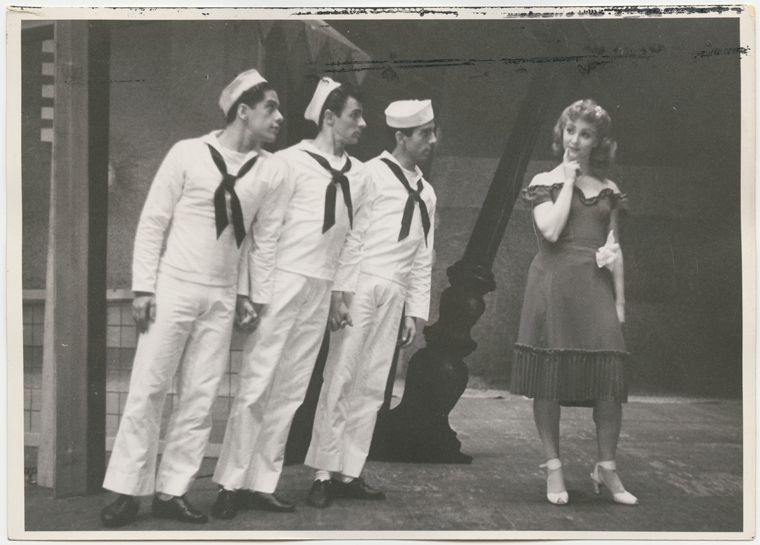

Which brought up another question: what does it mean to know someone only through his ballets, either by watching them or dancing in them? Increasingly, this is the primary way that we know Robbins. It seemed worthwhile, then, to try to show how these artworks emerged both from a particular person and a particular time and place. Fancy Free, Robbins’ break-out ballet of 1944, for example, came about because of his determination to choreograph an "American" ballet and his witnessing of the constant presence of sailors in the midst of World War II. So the exhibition gives a viewer a chance to see New York in the 1940s—primarily through photographs of where Robbins resided at particular moments in his life—and then trace how Robbins took the ubiquity of sailors around him to write an outline of a story, argue back-and-forth in letters with Bernstein about the music and Oliver Smith about the stage design, and dance in the ballet. The rare footage of Robbins dancing a solo in Fancy Free is then paired side-by-side with a later rendition of that same solo, danced by Christopher d’Amboise in 1981. We see the original and what made it—and then we see what changes and stays the same in how the ballet lives on. This is New York during World War II but also a story of camaraderie and competition among friends—one that has only become even more virtuosic as balletic technique has changed since the time it was created.

Finally, I saw the exhibition not just as an opportunity to praise Robbins—although there is much to praise—but to open up the city around us to his practice of turning living into creating. What might we create after observing how people spend their time in Central Park? (Footage of which is featured in the exhibition.) When a building that we lived in is razed for a new high rise, how might that experience become the setting for a story of young love? (West Side Story: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in the age of urban renewal.) What kind of movement and relations could be staged if inspired by the situation of all our friends living on the same block in the city, mingling social and artistic ambitions and anxieties? (See Interplay.)

Robbins was a consummate artist but he was also a tortured man, bedeviled by doubts and insecurities—these are on display in the exhibition as well. Even starting in his childhood, with an exacting mother, Robbins questioned his purpose, his abilities, and his place in the world. Being Jewish and sexually attracted to men only exacerbated these anxieties. While this constant questioning and pursuit of excellence may have fueled his ambition and talent, it also caused conflict with others.

It is hard to recommend him as a model to follow, given the pain he endured and inflicted. The point, then, is to focus not on just who he was and what he made—but on what he inspires. May we go out into the city around us with the same curiosity and attention and make something of it.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.