Awakening of Humanity Within the Framework of Classicism by Adrian Danchig-Waring

The following post is written by Adrian Danchig-Waring, principal dancer for the New York City Ballet, and a 2017-2018 Jerome Robbins Dance Research Fellow. The concentration of his ongoing research is the purposeful connection between reading Jerome Robbins' personal papers, and how that intimate connection with Robbins can be applied when Adrian dances. Danchig-Waring has found this practice results in a richer performance. Adrian has created the phrase "awakening of humanity within the framework of classicism" to describe Robbins' choreographic philosophy. This phrase defines the adherence to ballet technique as the universal language among New York City Ballet dancers, while the expression of humanity in the works is a unique qualifier of Robbins' choreographic voice.

2018. This is the year I cross a threshold where more than half of my life has been spent dancing for the New York City Ballet. By this point, the fast-twitch fibers of my being are woven into the tapestry of this storied institution: the house where Balanchine’s gospel still echoes down the halls. My body has been molded by the principles of his singular technique. His trademark style—spatially voracious and musically enervated—has rewritten my nervous system. Balanchine’s masterworks constitute the primary responsibility of stewardship at our living museum. But for some time, I’ve been preoccupied by a secondary expression of his genius: namely, the foresight he had inviting Jerome Robbins to join the company as a dancer and choreographer, naming him Associate Artistic Director, and thus ushering in a period of parallel experimentation which pushed the boundaries not only of what ballet could be, but also what it could mean.

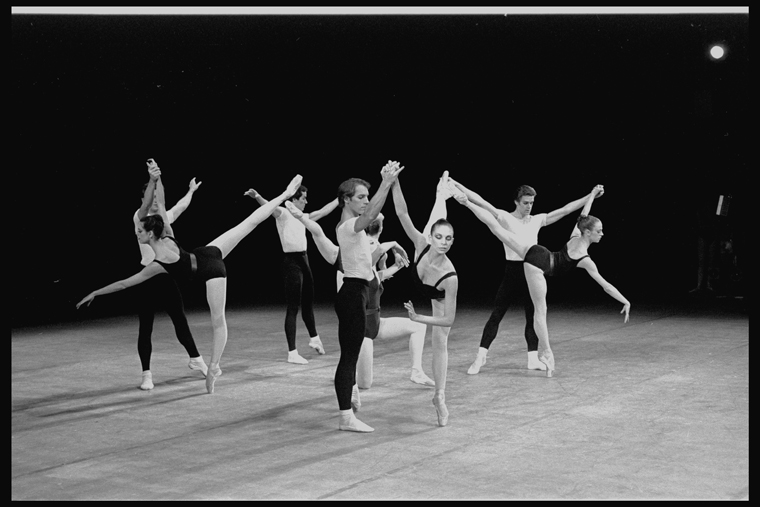

Balanchine’s most iconic works are what we call "Black and White Ballets," and they represent a radical, neoclassical reconsideration of balletic form. These works highlight the athleticism, physicality, and dramatic tensions intrinsic to ballet by stripping away the extrinsic ornamentation of costume and scenography. Balanchine put dancers onstage in simple, form-fitting practice clothes: black leotards and white tights for women and the inverse for men. These “Black and Whites” marked a significant departure from ballet’s long history of narrative construction and allowed dancing bodies to speak in a starkly visible and freshly voluble movement language. "You put a man and a girl onstage and you’ve got a story," Balanchine famously quipped. "A man and two girls; You’ve got plot." Jerome Robbins would later describe this as "the drama of space... because you deal with human beings and there’s always relationships… what interests you if there isn’t some sort of unconscious narrative." Neither artist rejected storytelling—they both worked extensively within narrative forms—but their sympathetic understanding and co-evolution of abstraction gave new impetus to ballet as a medium for communicating urgent modernist ideas.

It must be said that Robbins’ faith in the expressive impact of balletic abstraction only came into bloom alongside Balanchine’s already-cultivated garden. And though Robbins was clearly influenced by the older master, their parallel experimentation within the context of the New York City Ballet produced wildly divergent strains of neoclassical ballet.

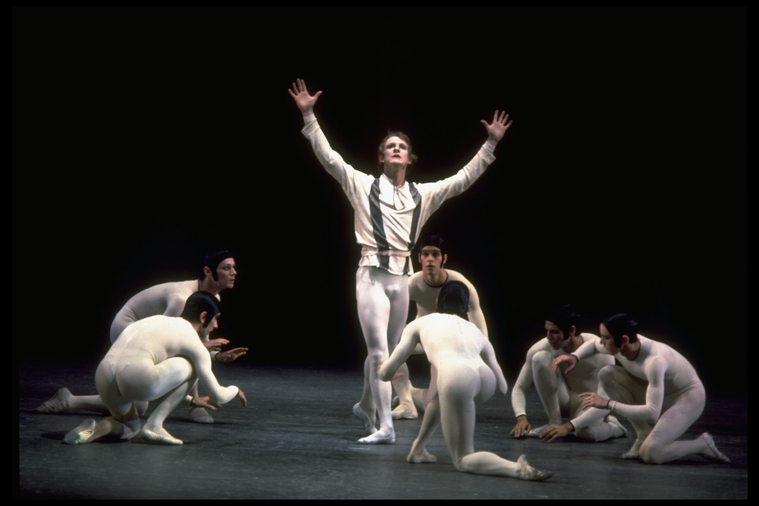

As a dancer, I feel that their respective works vibrate at different frequencies, and a significant aspect of that difference lies where, within the dancing body, they demand attention. If Balanchine’s works are responsible for shaping my technique and outward physicality, Robbins’ works have cultivated an equally demanding attention to my inner life. Robbins’ ballets get to the heart of something I call the awakening of humanity within the framework of classicism. They require me to be a real person as I occupy the stage space: to excavate my true self and breathe it naturally through the skin of the dance. This is not always a given in the world of ballet, but in a Robbins ballet it is both mandatory and essential. The outcome is that my colleagues and I are required to self-reflect, to analyze, to learn ourselves deeply, and to bring those more realized selves back to the work.

For dancers seeking points of access into the inner life of Robbins’ ballets, there are clues peppered throughout his oeuvre which either directly or obliquely reference aspects of specific times and places: folkloric steps from the old country, for example, or present-day vernacular dances like the lindy hop, the mambo, the cha-cha. He took everything that he saw around him and mined it for signifiers of universal humanity. Then he molded it, meticulously, around the armature of classical ballet. It wasn’t filigreed; it was plain and simple. Robbins' great gift, then, was in augmenting the classical ballet language with a newly modern sense of humanity, wit, and interiority. He described this as the "element of human experience which creeps into (the work) whether I want it to or not." This accounts for the sense of community dancers describe feeling while dancing his ballets. We are social animals, after all, and when our art mirrors our lives, it strikes upon something both real and true.

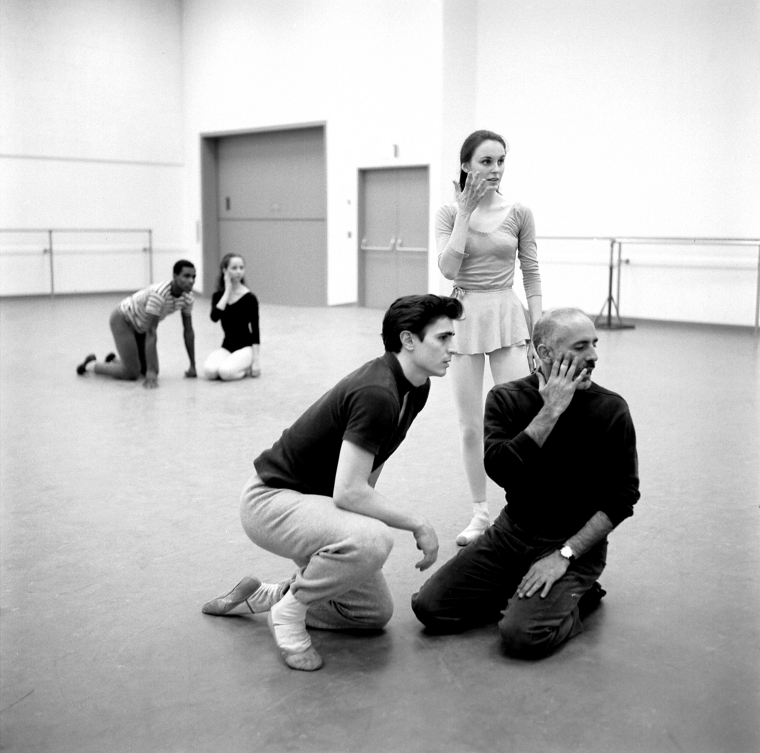

I’d like to note that growing up within a ballet company is, in many ways, parallel to being raised within a family or perhaps a small, proud village. There is a hierarchical system through which each generation of dancers emerges, fledgling, as apprentices. They must prove their worth as contributing members of the larger corps de ballet to gain societal acceptance. Some excel and climb to soloist and principal ranks, all the while navigating the challenges of deep interpersonal relationships amongst colleagues, forever magnified by the outsized presence and authoritarian power of a (generally) patriarchal figure (the Artistic Director) who manipulates career progressions, stagnations, and terminations. Yet, through all of this, there remains an inclusive sense of participation in a collective and continuing history.

It cannot be overstated how essential this familial structure is to the stewardship of the ballets we dance. The nature of our work is so grueling that we need to feel a bone-deep connection to the company in order to persevere within it, and thus preserve the ballets that made us what we are. The company furnishes its dancers with a pride of place, generating both a sense of belonging and the perpetual need to belong—a duality which requires fierce loyalty to your friends, lovers, colleagues, and "father" figure. So, it’s not surprising that we speak with a combination of loving intimacy and reverence when we talk about our founding choreographer "fathers." The reverence manifests in the ubiquity with which we call Balanchine "Mr. B," and the intimacy takes form when we call Robbins "Jerry." The use of these specific titles has been passed down from the previous generation of dancers, those who worked directly with the masters and now serve as ballet masters themselves. It’s indicative of a certain level of closeness that we only ever refer to the celebrated artist Jerome Robbins as "Jerry." And I believe the intimacy of this language emanates from the profound connection one feels to this maker when embodying his works.

Dancing a Robbins ballet feels like intimate contact with Jerry, in a way that feels more personal and directly relational than dancing in a Balanchine work. To learn, rehearse, and perform Robbins’ choreographies is to open a portal not just into his particular way of thinking, but also into his process of feeling, during a specific period of his creative life. In his words, "You absorb both your time past and you absorb the age you’re at, and the vision you have, and you absorb what’s happening around you." His ballets function as a conduit between the time of creation and the present moment, like a period of ritualized communion between choreographer and dancer. This particular feeling of closeness, or proximity to the source, has been a constant for me as I’ve learned, rehearsed, and performed some 19 different Robbins ballets over the course of my career (and many in multiple roles). And while all that choreographic information has surely influenced my dancing, it has also held up a mirror to my personal development and provided an anchor while I navigated the vicissitudes of young adult life. Wherever I was, whatever I was going through, I could always pour myself into the work, and the work would consistently reveal new depths.

As disparate as the ballets in Robbins’ canon may appear at first flush—differences magnified by musical variation, shifts in mood and atmosphere, explorations of narrative construction or abstraction—the way they reside in the dancing body is always a familiar return to Robbins' singular voice. There are certain dance sequences, spatial patterns, and movement phrases that recur from one work to the next. There are rhythmic time signatures, syncopations, and ways of hearing music that are consistent throughout his cannon. There is an emphatic attention paid to the focus of the eyes, to the use of actual sight, and the connections we make with each other through intentional eye contact. But underlying all of these social and structural through-lines is a faithful adherence to the principles of classical ballet.

Jerry carried a lifelong concern for the limitations of any singular technique, yet he came to believe ballet was the ideal medium through which his explorations of interiority could most effectively manifest as performative gesture. Though his early training came piecemeal from the "Disciples of the Gods of Modern Dance," a spectrum ranging from pseudo-Duncanesque scarf dancing to calcified Graham technique, Robbins slowly came to see that, as he said,

“Each (technique) is only a vocabulary—a language to use as a principal to express dancing. Certainly Balanchine and Graham in their respective areas love pure dance and create their works almost antiseptically thru (sic) pure movement. Each is also a grant of the theatrical when each wishes to use it—but the drama of theater is made thru the drama of a body moving thru space in metric and special orders."

Robbins prized classical ballet for its particular alchemy of metric, spatial, and—above all else—expressive order, and I believe the cornerstone of his genius was his fluency in, and masterful augmentation of, that tried-and-true language.

What Jerry articulated so succinctly stems from his recognition that the human body has finite capabilities. It is limited by its own biology and must abide the laws of physics. He argues that we cannot merely rely upon the inherent movement patterns, biomechanical habits, or intrinsic feeling of each individual’s body. Instead, we must learn to cultivate an extrinsic language, something initially foreign for every body. Only then is it possible to find the common vocabulary necessary to produce meaningful work. As he put it, "The ballet rules are functional. They educate the dancer in the use of his body and provide a common language between the dancer and choreographer."

This runs parallel to the way in which language makes communication not only possible, but also adaptable. Language, by necessity, reflects its ever changing environment. Linguistic evolution is therefore predicated upon having a common yet intrinsically flexible foundation. The fundamental question Jerry poses is that "We must ask ourselves if our techniques are helping us develop in the direction that gives us the greatest range of communicative expression. The big “Why” we must put to everything we are doing is not a theoretical one, it is a matter of artistic necessity." This mandate for tireless inquiry and constant analysis are the cornerstones of Jerry’s creative practice. Implicit to his choreography is a demand that dancers must do the work to bring themselves fully to the process in order to convincingly embody the "unconscious narratives" he generated. In other words, we have to show up.

The specificity of Jerry’s language—read as a clarity of choreographic intent—has awakened in me a newfound faith in ballet as a perfect and self-contained language system. This is particularly significant because we now live in a time where many of ballet’s historical structures (patriarchal, hierarchical, and racially homogeneous) do not reflect our shared reality or progressive values and, rightfully, are being questioned. I believe there is a pure form of ballet, independent from the burden of history, which can speak to our times. This is the technique which Jerry identified as a tool of broadest communicative expression. And, born of his conviction, I now have a growing confidence in the classical form’s adaptability amid the churning complexities of our contemporary world. It’s not that ballet should directly address current issues, political or otherwise. On the contrary, ballet tethers us back to the human body, and therefore builds upon something timeless, familiar, universal. The technique’s baseline neutrality allows it to serve as a sponge to the ebb and flow of an idealistic ever-shifting zeitgeist. Ballet shares this malleable quality with Robbins himself when he says "You absorb both your time past and… you absorb what’s happening around you." As with the maker, so too with the medium. They are similarly susceptible, responsive, and reflective of their given time and place.

At its highest good, ballet functions as a mirror to our changing society. There is good reason the art form has endured five tumultuous centuries of western history. We need not understand its potency in intellectual terms for it to work its magic. Jerry would remind us that "If you asked Mr. Balanchine, 'What does a flower mean?' he’ll say it’s beautiful. And he stops there." Robbins would insist that "It’s not necessary to analyze it and say it means something." He’d tell us that he is firmly against intellectual interpretations. And so, for the time being, I’ll avoid such interpretations allowing instead for my body to do the talking.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.