Connected Choreography? Nijinsky's "Faune" & Robbins's "Faun"

Jerome Robbins, world renowned choreographer of ballets, and choreographer of theater, movies, and television, would have been 100 years old in 2018. Join us this year as we celebrate the life and work of Jerome Robbins with discussions, performances, staged readings, children's programs, and an exhibition opening in September.

This month, we will begin a monthly series in which writers, researchers, friends, and colleagues of Robbins will contribute a blog on a topic of their choosing. Our first blogger is chief dance critic for The New York Times, Alastair Macaulay, with a preview of his fellowship project that will be presented in more detail at the Robbins Symposium on January 26, 2018:

The Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts has been part of my life since my first morning in the city. (That was January 1979. In those days, the name was the Dance Collection, not Division.) Much of my dance education has occurred—is still occurring—there.

Since 2012, the Division has been generous in letting me organize a series of seminars on individual ballets, each recorded for its archives: “The Sleeping Beauty” (two afternoons, 2012), “Swan Lake” (three afternoons, 2013), Balanchine’s “Serenade” (three afternoons, 2015), and “Giselle” (three afternoons, 2016). I hope the Library has profited; I know I have. There are few achievements in which I take greater pride, though in each case I have been more student than expert.

In return (this was cheerfully stipulated in 2012 by Jan Schmidt, the then-curator of the Dance Division), the Library has asked me to present or co-present an evening event, including some of its rare films and illustrations, as the fruit of each seminar. So I, with colleagues (Robert Greskovic and the late David Vaughan), have presented evenings on “The Sleeping Beauty” (2013), “Swan Lake” (2014), “Serenade” (2016); and in 2015 I also presented an event of rare or unique films of the Royal Ballet. (Though various delays have held up the “Giselle” event, we certainly hope it will happen.)

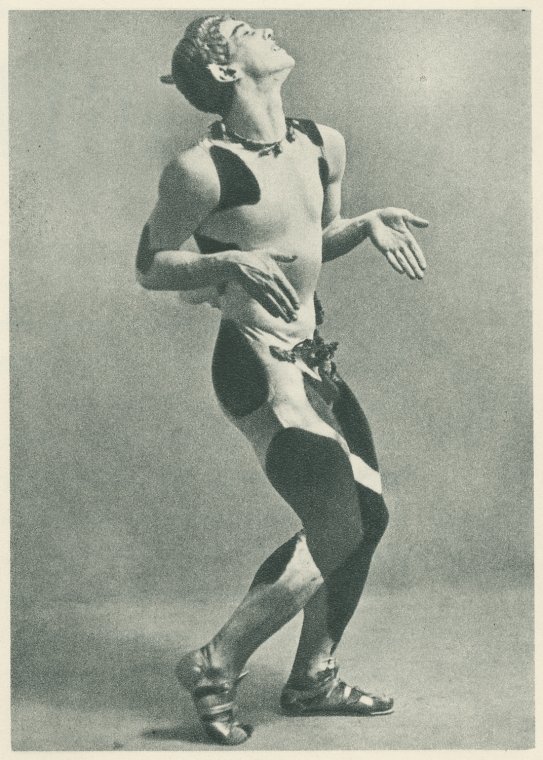

My 2017 project has been to investigate the connections between Vaslav Nijinsky’s “L’Après-midi d’un Faune” (created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1912) and one on Jerome Robbins’s “Afternoon of a Faun” (1953, made for New York City Ballet, with a set and lighting by Jean Rosenthal). A child can see the differences between these two classics. Nijinsky’s is set in the ancient world, with designs by Leon Bakst; the movement is two-dimensional, like a bas-relief in motion. Robbins’s occurs in a ballet studio, designed and lit by Jean Rosenthal: the dancers not only move three-dimensionally but also refer to the unseen fourth wall as if it were the studio mirror.

So what are the connections? Most obviously, they’re both set to the same musical masterpiece, Debussy’s “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune” (1894), a score that seems to resist dance in its lack of dance meter. There are also other links… Yet, before proceeding further, I needed to organize seminars on each ballet.

So, thanks to Curator Linda Murray at the Dance Division, the centrepieces of my research have been two invitation-only events in the Library’s seminar room: one on the Nijinsky “Faune” (May 15, 2017), one on the Robbins (August 28, 2017). I had no special expertise on either work, but I knew a number of those who do. I knew that people differ on how each ballet should be performed, on how each used that Debussy score, and on the nature of the drama within each one; and I knew whom to invite and what questions to ask. I’m also not bad at collating historic footage and images of choreography from the Library’s vast collection. As in previous years, Producer Daisy Pommer of the Dance Division’s original documentation department and her colleagues made the logistics of showing films and photographs seamless.

These seminars were not open to the public; I felt it was important that each speaker should feel as relaxed as possible, without the added stress of public presentation. But each was filmed—excellently—by Francois Bernadi for the Library. Future scholars of either ballet will learn volumes from each, as I have.

Each seminar began with the assembled company looking at old films and photographs. This established something of each work’s performance history, but also to stimulate discussion. What followed pooled a very considerable amount of wisdom from different sources.

“Who knows dancing who only dancing knows?” The motto is the critic Arlene Croce’s; I try to be true to it. Both seminars included the Princeton musicologist Simon Morrison (at short notice he could not attend the Nijinsky one, but sent words which I read on his behalf). Joan Acocella, dance scholar and contributor to The New Yorker, combined both her expertise on Nijinsky and her knowledge of psychological and sexual terminology to the Nijinsky session; Lynn Garafola, professor emerita of dance at Barnard College, spoke of Diaghilev and Nijinsky in context of Russian and French theatre, while Deborah Jowitt, critic and Robbins biographer, introduced, among much else, the issue that Robbins made “Faun” precisely when he was answering questions—with perpetually damaging consequences—to the House Committee for Un-American Activities about his knowledge of communism and American communists. Speakers at the Nijinsky event included the art scholars Juliet Bellow (speaking about Nijinsky and Rodin) and Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen (about Bakst) and the musicologists Rachana Vajjhala and Daniel Callahan (acute on points of Nijinsky’s choreographic musicality). At the Nijinsky one, Mindy Aloff, dance scholar and professor at Hunter College, spoke about Edwin Denby’s essays on Nijinsky photographs and on “Faune”; at the Robbins one, she spoke about Jean Rosenthal. Nancy Reynolds, Director of Research for the George Balanchine Foundation, spoke about Lincoln Kirstein’s advocacy of Nijinsky’s choreography at the former and contributed memories of the original cast at the latter, as did dance critic Nancy Goldner. Ann Hutchinson Guest, the preeminent authority on dance notation, spoke of deciphering Nijinsky’s own notation for “Faune” and of the revelations it contained of both choreographic musicality and dramatic action.

I remember times past when dancers and academics moved in opposite paths, and when dancers felt shy of speaking analytically in the presence of others, even about the subjects they knew better than anyone else. So it was marvellous in both seminars to hear the contributions of dancers and ex-dancers. Michael Novak, a member of the Paul Taylor Dance Company who danced the title role of Nijinsky’s ballet in a Columbia/Barnard co-production in 2009, spoke of having to learn how make stillness register in dance terms in Nijinsky’s choreography; like Steven Melendez and Elena Zahlman (both of New York Theatre Ballet), he also spoke of how important it was, having mastered the details of the movement, then to find the motivation for each situation and indeed each movement.

On Robbins, the contribution of the dancers was yet more central—some before the seminar began. Afshin Mofid, who at one point in the 1980s was the sole interpreter of the male role at New York City Ballet (partnering Maria Calegari, Suzanne Farrell, Darci Kistler, and Kyra Nichols), knowing he could not attend and prompted by questions from me, sent me a superb 1500-word piece of his memories. Likewise, Calegari wrote me almost as much. These two, with their marvelous attention to detail and to overall qualities, set the tone. Mofid: “[Robbins] would go back to Nijinsky sometimes but then would fast-forward to present time and the three-way relationship of Faun, the girl, and the mirror. It was at times like method acting, where you have to have a motivation behind each line of the dialogue. Since there were no ballet steps for the boy in his version, each move had to have a purpose and a thought behind it or it would be totally void of meaning and intention.”

And Calegari wrote: “‘Narcissism,’ though people have used it about ‘Faun,’ is such a strong word; I feel it diminishes the beauty of the ballet. The mirror is a challenging aspect of ballet and how you use it and see yourself. It’s quite beautiful the way in ‘Faun’ they show the audience how they work with it—and how clever: the dancers go in and out of just dancing with each other and then as a way to break the building tension they look back at the mirror. They reach to each other, but still looking at the mirror, as they cannot quite just be together alone without it.”

The August 28 Robbins “Faun” seminar included five dancers who had been coached in “Faun” by Robbins between 1961 and 1989: Kay Mazzo, Ib Andersen, Jean-Pierre Frohlich, Robert LaFosse, Jeffrey Edwards, as well as a post-Robbins interpreter, Sterling Hyltin. They quickly established two points of importance. First: Robbins thought of almost all his dance works more as plays than ballets, and encouraged his dancers to find and develop their own motivation; he would allow them to change small points in the choreography as long they were true to their own vision and to the ballet’s overall mood. (La Fosse: “I was a choreographer, and I’d run out of ideas. The whole ballet was my dream.” The opening solo was to do with the testing of new ideas.) Second: the best-known film of “Faun,” with Le Clercq and Jacques d’Amboise in 1955, was made without Robbins’s consent or approval, and is furthest from what he wanted. (In it, D’Amboise is more knowingly assertive than any other interpreter of the lead role, while Le Clercq adjusts her performance—also recorded on a 1953 silent film with Francisco Moncion—and makes it far less innocent and artless.)

Much more was said. And I will say more at the Robbins Symposium on January 26, 2018, I hope to say more. This has been just by way of “preview of forthcoming attractions.”

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.