The New York Public Library's "Ghosts" File

Genealogy librarians answer questions from patrons who seek to bring the dead back to life.

We are necrologians. We help people raid graves where the data of the departed is alive.

We also answer questions about the history of New York City, a place where zombies ride the subway, monsters build black and gold skyscrapers, and gargoyles outnumber rent-stabilized apartments.

The NYC clippings files collection in the Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History, and Genealogy includes a small file on the subject “Ghosts.”

And though librarians might be trusted by the public as fosterers of fact over fiction, to debunk the presence of ghosts using historical records might still involve a certain possession by the spirit world.

Spinster of Noho

The annual Candlelight Ghost Tour is held at the Merchant's House Museum at 29 East 4th Street. As recounted in a 2010 clipping from Chelsea Now, Gertrude Tredwell "was born, and died, in the house." Ms. Tredwell lived to the age of 92, and her father, Seabury, was a hardware merchant who in 1865 left ten thousand dollars each to seven of his eight children, out of which brood one son and four daughters lived in the house and never married. Each sibling predeceased Gertrude until she was the lone occupant, an octogenarian in the Jazz Age whose Greek Revival dwelling was still furnished as if Ulysses S. Grant was still President.

A nephew of Gertrude lived on the third floor until his death in 1930. She died in 1936. “The blinds were kept closed in the drawing room; the dining room was never used, and the dust of years accumulated” (NY Times, May 3, 1936).

Restoration workers claimed to have seen Gertrude standing in the doorway one year following her death. Tourists in the 1980s said that she answered the door when they buzzed the ringer.

In the Chelsea Now article, the reporter joins a “paranormal researcher” on a tour of the house, and claims he felt a tingling sensation on his right arm while standing in the rear parlor; the numbness might have been Gertrude communicating the experience of what it was like to watch the same neighborhood in New York City transform over ninety years into nothing she could recognize or would remember.

The Amity Lane Horror

A 1994 New York Post article "drops in on some haunted houses," with lore about the spirit of timber-legged Peter Stuyvesant rising from his grave in the churchyard of St. Mark's-in-the-Bowery, where today the old Director-General rubs shoulders with the ghosts of Joey Ramone, Kim's Video, Quentin Crisp, Tompkins Square Books, and Mars Bar, where the bathroom was truly a horror show.

A number of other locales in the article are today ghosts of a different city whose spirits return to haunt Manhattan in the form of organic gourmet food courts and bank-ad two-wheelers. Breezin’ Restaurant, on Mercer Street, owned by folkman suicide victim Phil Ochs; DaVinci’s Restaurant, where the ghost of an alcoholic Madison Avenue advertising executive used to leave empty martini glasses on the bar and scribble slogans on the walls; and Café Bizarre, “where the ghost of Aaron Burr used to prowl,” at 106 West Third Street, the building since demolished and replaced by D'Agostino Hall.

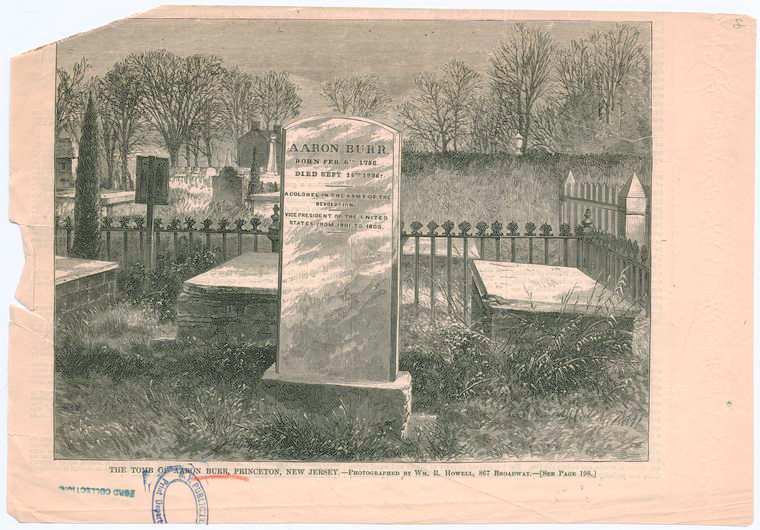

A handful of Manhattan city directories dating between 1790 and 1830 show addresses for Aaron Burr at 30 Partition (Fulton Street between Broadway and West Street), “Richmond Hill” (an mansion at Charlton and Varick Streets), 4 Broadway, 52 Broadway, 61 Vesey, 45 Cortlandt, 55 William, and at 221 Broadway while Vice President of the United States. Many of these were business addresses, and not places of occupancy.

There are no addresses listed for Amity Street, the old name for West Third.

A 1955 Manhattan Land Book shows 106 West 3rd Street in between MacDougal and Sullivan Streets. The traces of Amity Lane, a diagonal forefather of Amity Street that ran through the lots where 106 West Third was later located, are also shown. The proposal for landmark designation submitted to the city notes that Aaron Burr bought some of this land, in addition to property west of Sixth Avenue.

A Dutch land grant in 1644 that included the West 3rd Street block went to Paulo d'Angola, who arrived in New York enslaved in 1626 on the ship that transported the first black men to Manhattan Island, and who successfully petitioned the Dutch West India Company for manumission.

Southwest of this vicinity, Aaron Burr dwelled at Richmond Hill, “the mansion where Washington had lived in 1776, with grounds reaching to the Hudson, with ample farms, and a considerable extent of grove and farm.” In 1776, one of the housekeepers for Washington was Phoebe Fraunces, the daughter Sam Fraunces, proprietor of Fraunces Tavern. Phoebe advised the General that a spy for the British named Hickey planned to assassinate Washington by poisoning his favorite dish of black-eyed peas. Hickey was apprehended and executed.

The mansion was located at “the city block encompassed by King, Varick, Charlton, and MacDougal Streets," an area known in antediluvian NYC as "Zandtberg," or the Sand Hills.

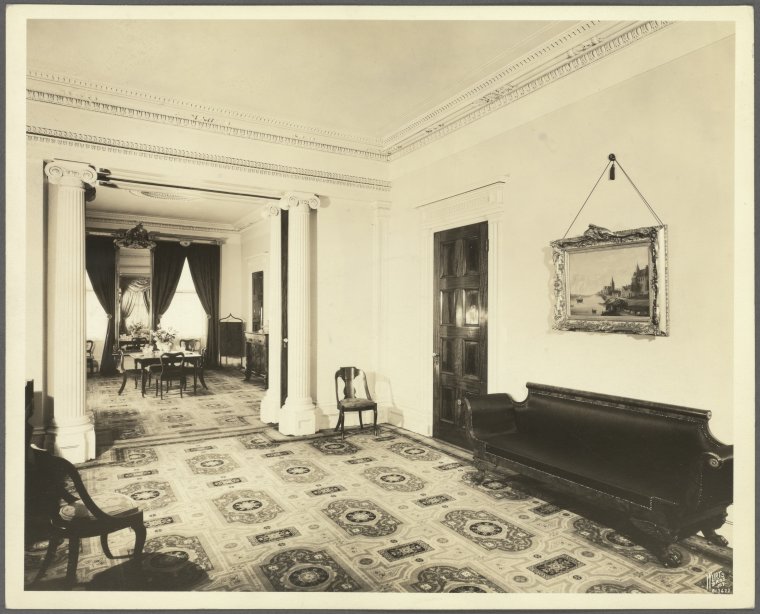

"Few houses in America,” writes a 1907 biographer of Theodosia Burr, the Colonel’s daughter, “have sheltered so many prominent men and women, or experienced more vicissitudes of fortune and use, than the one time home of Aaron Burr known as Richmond Hill."

Vice President Adams occupied the house in 1789, the year New York City was capital of the United States. Abigail Adams was awed by the vista from the high grounds and wrote her sister that "in front of the house the noble Hudson rolls his majestic waves, bearing upon his bosom innumerable small vessels, which are constantly forwarding the rich products of the neighboring soil to the busy hand of a more extensive commerce. Beyond the Hudson rises to our view the fertile country of the Jerseys, covered with a golden harvest, and pouring forth plenty like the cornucopia of Ceres."

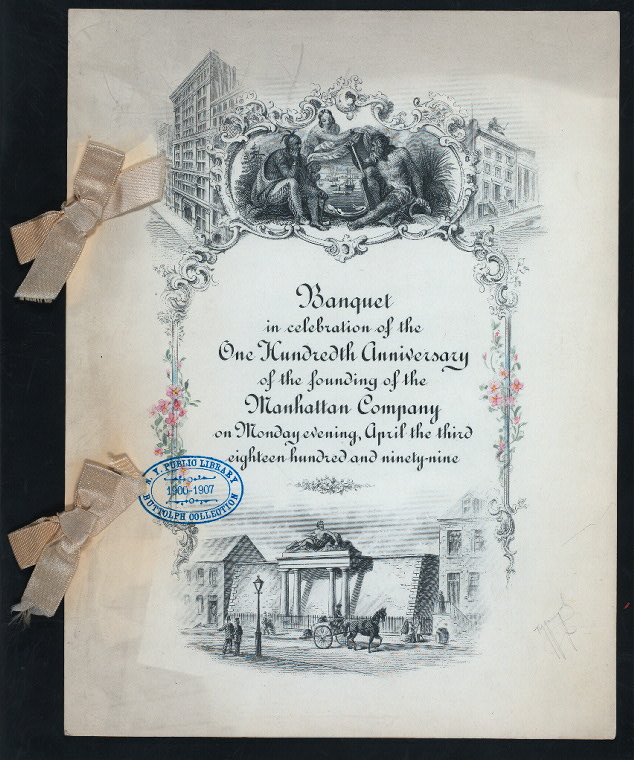

An 1803 land conveyance appears to show Aaron Burr accepting $47,000 from the Manhattan Company in exchange for numerous lots on the Richmond Hill property.

Burr formed the Manhattan Company in 1799 to provide the city a source of fresh water during a plague of yellow fever; it was soon obvious that through a sly use of wordplay in the charter, Burr used the water-works funds to found a bank, while the “black vomit” continued to depopulate the island.

The specter guide Ghosthunting in New York City describes 106 West Third as the site of a stable once owned by Aaron Burr, citing an 1995 article in the NY Times. This would seem an unlikely distance from the 160 acres of the Richmond Hill property, but the author claims that when John Jacob Astor bought Richmond Hill, at one dollar an acre, the real estate maven relocated the stable from its site near the mansion to the future Amity Street location. It is unclear where this information was derived.

It might be, that if the building was in fact haunted, the ghost was not Burr, who is buried in Princeton, New Jersey, but the shooter-of-Hamilton’s horse.

West Side Uxoricide

A 1992 clipping in the Manhattan Spirit recounts an 1891 spouse-killing at 32 West 40th Street.

Carlyle W. Harris was a medical student at the College of Physicians and Surgeons on West 59th Street. His family lived in South Jersey, where Harris spent much of his leisure time, “well known to the summer cottagers and hotel guests of both Asbury Park and Ocean Grove.”

Indeed, in 1889, the young and cocky Harris was arrested for operating a poker room and brothel called the Neptune Club, two blocks from the ocean.

That same year, he met eighteen year-old Helen Potts, an honors graduate from Asbury Park High School whose father was a noted Jersey railroad contractor. Harris frequently called on Helen at the apartment at 116 West 63rd Street where she stayed with her mother in Manhattan. While giving the appearance of an innocent courtship, the two made stealthy arrangements to secretly wed at City Hall using fake names. When the Alderman asked for the maiden name of his mother, Harris gave "Potts."

The real Mrs. Potts was not charmed by Harris. “The mother stood away from them; she could not bear to be near him," but "she noticed the way her daughter looked up at this man; the love that was in her eyes, and she could not make up her mind to separate them.”

Helen was pregnant, and in the second trimester Harris, the medical student, attempted to perform an abortion, twice, and failed. Sick, fearful, and in pain, Helen traveled alone to Scranton, PA, where her uncle, Dr. Treverton, completed the botched procedure and saved her life.

While Helen recovered from the torture inflicted upon her, Harris was in Canandaigua, New York, carrying on with a woman named Queenie Drew and using the alias Carl Graham.

Helen revealed the marriage to her mother; Harris balked at agreeing to a formal ceremony to legitimize and make public the union.

Instead, he convinced Helen to enroll in the Comstock School for Young Ladies, at 32 West 40th Street, where she resided through the new year and studied music and languages.

Helen complained of chronic migraines and Harris illegally obtained a prescription for capsules of quinine and morphine to treat the headaches.

In the middle of the night on January 31, 1890, Helen went into a stupor in her room at the Comstock School, and fell unconscious. Abject attempts to revive her were made, and the initial cause of death was labeled “morphine poisoning.”

Mrs. Potts did not make it known that her daughter was married, and Carlyle Harris was initially described as a friend.

It was soon discovered that twenty days before the death of Helen Potts, her husband attended a lecture at the College on “morphine poison, its effects, its proper uses, as well as its felonious uses.” The Assistant D.A. in the eventual murder case against Harris asked with a lawyerly flourish “whether or not this fact played any part in suggesting to the defendant the particular method he should employ in ridding himself of his girl-wife.”

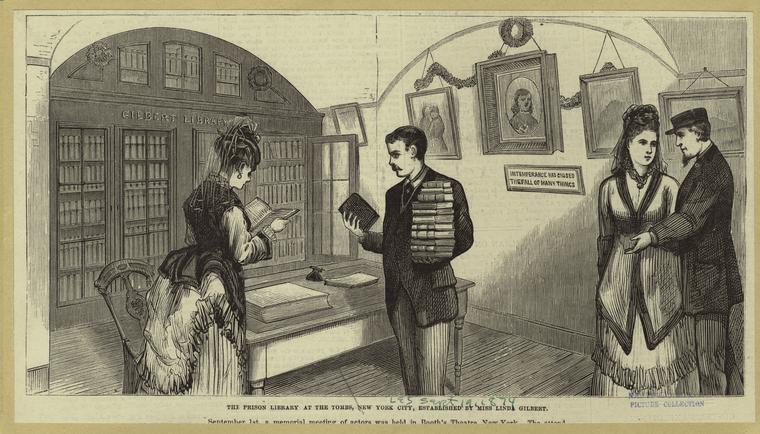

After the marriage was disclosed and an autopsy performed on the disinterred body of Helen, the guilt-protesting husband was arrested and spent ten months in the Tombs awaiting trial for Helen’s murder, which was covered heavily in Mauve Decade newspapers and took place in the Court of General Sessions. Records of this New York County court are held at the Municipal Archives.

It was determined that Harris had increased the morphine dosage in Helen’s pills to a lethal level. Witnesses claimed that when Harris was first told of the death of his secret bride, he incriminated himself by exclaiming, “Great God, what will become of me?”

His mother, Frances McCready Harris, fervently pled his innocence, and in quotes to the papers portrayed Helen as a conspiratorial morphine addict. Prosecutors made it clear that she was a victim of Harris’ predatory ice-veined brutality.

In 1893, Harris was electrocuted by the State of New York.

There was testimony in the trial that Harris had performed at least five abortions on former girlfriends, and had consummated two previous marriages. His method of conquest was to slip whiskey into a woman’s ginger ale in order to inebriate her to the point of submission to his advances. When date rape did not work, he employed matrimony, in order to sanctify the seduction, as in the case of Helen Potts. The child which Dr. Treverton had induced to be delivered was conceived in February, the month of the secret marriage.

At the time of the murder, Harris was living at the residence of his grandfather, Benjamin W. McCready, an esteemed New York City doctor, at 28 East 17th Street, which an 1868 Perris and Browne map shows was a six-story apartment house with an elevator. An 1893 NY Times article published on the eve of the execution mentions that Harris kept the marriage secret out of fear that his grandfather would otherwise disinherit him. He had no income and relied on old man McCready for habitation, and marriage might have qualified him as a male adult earner in the social Darwinism of the gaslight era.

Dr. McCready died in 1892, while the murder trial was still ongoing. The ninth term of the will firmly declares that "in no event shall my grandson Carlyle W. Harris receive either under this my last will and testament or under the power of appointment given hereinto either of my daughters any portion of my said estate." For Carlyle's mother, Frances Jane Harris, the will provided for all legal fees.

The obituary for McCready in the New York Tribune indicates that in his early years as a doctor he worked as “the physician at the Tombs,” where his grandson would later write a detailed memoir account of his daily incarceration, in addition to articles and poetry.

32 West 40th Street, the site of the death of Helen Potts, was a modest rowhouse that was replaced in 1907 by the construction of the Engineers Club, a mens fraternity like the Friars Club but instead of zinger-slingers and knockabout acts it admitted metallurgists and the president of the Spiral Weld Tube Company.

The Manhattan Spirit article in the “Ghosts” file claims that on the anniversary of the death of Helen Potts, the young woman cries out in the halls of the new building—a spirit as displaced as the Comstock School for Young Ladies by the Engineer’s Club for men—and “complains about her migraines, that nothing’s strong enough to cure them.”

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.