Biblio File

A Banned Book in the Spencer Collection

Banned Books Week 2017 is this week (September 24th–30th). With that in mind, I would like to introduce a beautiful book, once banned, now residing in the Library’s Spencer Collection. It is a work of no particular bibliographical significance: an isolated volume (volume 2, the correspondence) from a ten-volume set of the works of St. Augustine.

The editor of the collected edition was the great Renaissance humanist Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, and the collection was published originally in Basel in 1528–1529. No fewer than ten reprint editions were published over the next half century, among them one in Venice in 1550–1552, from which the Spencer volume was taken. A digitized version of another copy is here.

The Venetian publisher is known today only by his shop sign, an allegorical representation of Hope. “All’insegna della Speranza” or “Ad signum Spei” (“At the sign of Hope”) is how he is identified on the title pages of the works he published, accompanied by his publisher’s mark: a small illustration of Lady Hope, with a motto from the book of Psalms, “Beatus uir cuius est Dominus spes eius & non respexit in uanitates, & insanias falsas,” or in the Douay-Rheims translation of the Vulgate, “Blessed is the man whose trust is in the name of the Lord; and who hath not had regard to vanities, and lying follies” (the Latin has “spes,” or hope, where the English has “trust”).

The Venetian edition is quite rare, at least outside of Italy; I could only locate a handful of copies elsewhere in Europe and in America. I speculate that part of the reason for this is the fact that Erasmus was persona non grata to the church officials of the Counterreformation who were, just at this era, determining the nature and extent of the enemies lists that were to become notorious, in various versions, under the name Index librorum prohibitorum, or “Banned Books List.” The earliest papal version of the Index (1559), published under the auspices of Pope Paul IV, actually singled out Erasmus in its listing of those writers whose entire oeuvre was banned: “Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus, with all of his commentaries, annotations, scholia, dialogues, letters, evaluations, translations, books, and writings, even if they contain nothing against religion, or about religion.” (See the illustration. I don’t think the pictorial “D” is meant to be our man Desiderius, but except for the beard, it bears a certain resemblance.)

By the terms of a decree of the Inquisition preceding the Index proper, all Christians were forbidden to copy, publish, print, buy, sell, lend, borrow, give, receive, or possess any of the books or writings listed in the Index; anyone who disobeyed was subject to excommunication and an array of penalties including suspicion of heresy and the forfeiture of all offices and dignities, which were nevermore to be restored. Anyone who was in possession of such books or writings when he learned of the decree was ordered to hand them over forthwith to the local bishop or the representatives of the Inquisition, or else. The usual fate of the confiscated volumes was to be publicly burned.

The Index was considered excessively harsh, even by some Catholics, and soon after publication, the Pope was persuaded to soften it somewhat. Some copies of the 1559 edition, including NYPL’s, contain an appended paragraph beginning “De libris orthodoxorum patrum ...” This allowed people to own works of the Church Fathers (and other authors not on the Index) who had suffered the misfortune to have been edited by heretics, but only if written permission from the Inquisition were obtained, and that would only be granted if previously the names, annotations, scholia, evaluations, arguments, summaries and all other traces of the thought and activity of those authors whose works were banned in the Index in their entirety had been erased or so thoroughly stricken through that they could not be deciphered.

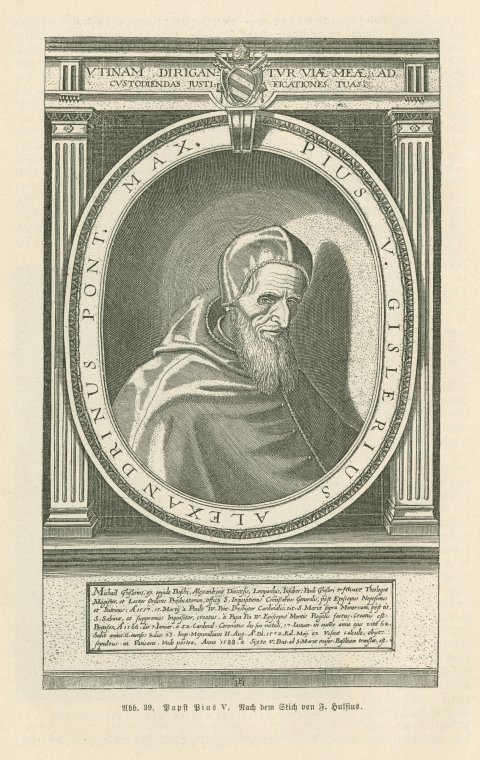

One of the most important of the church officials involved in creating and enforcing the Index was the Grand Inquisitor, Cardinal Michele Ghislieri; he has been called the soul of the project to extirpate heresy from Catholic lands. In 1566, Cardinal Ghislieri was elected Pope, taking the name Pius V. And that brings us back to the Spencer volume of St. Augustine’s correspondence. It is preserved in a lavish Roman Renaissance binding of luxurious red morocco, replete with gilt tooling, with floral and armorial ornaments painted on and impressed into the gilt edges of the pages, and with two leather and brass clasps and eight gilt bosses on the boards. The binder may have been Niccolò Franzese, a Roman binder employed by the Vatican library at the time.

The ornamentation proclaims and explicitly spells out who the mighty prince was who commissioned this masterpiece of the binder’s art to house the letters of a saint: Pius V, P[ontifex] O[ptimus] M[aximus]; the Ghislieri arms are crowned with the crossed keys and the triple crown of the successors of St. Peter.

When we open the volume, two revelations reverberate across the centuries. The first is that this copy of a banned work, formerly owned by one of the Banners-in-Chief, has indeed been duly censored: Erasmus’s preface to the reader on the title page verso, his only textual presence in the book, was once covered by a pasteover, the residue from which has damaged the page in question.

In addition, the words “Des. Erasmus Roterodamus” have been heavily lined through in ink.

After this treatment, I am sure the man who commissioned the binding found no difficulty in obtaining permission from the Inquisition to possess the book.

The second revelation is a more subtle grace note of irony. Aside from two small historiated initials, the only ornamentation present in this austere edition, as it came from the press, is the publisher’s device on the title page illustrating “Ad signum Spei.” In an exquisite cut barely 55 x 44 mm, it portrays a female figure turning to the sun of Hope, as she rejects worldly goods.

Prominent in the mishmash of objects she consigns with her left hand to the trash heap of "vanities and lying follies" is the papal crown.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.