From Boston's Resistance to an American Revolution

The American Revolution is usually told as a very Boston-centric story. When Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, resistance was widespread, but Bostonians led the way in creating the Sons of Liberty. Textbooks often gloss over the next five years, until the story picks back up with “The Boston Massacre” in 1770. Despite the bloodshed, tensions seemed to calm for a while. That is, until Bostonians had a “Tea Party” in 1773. Outright warfare came only about a year-and-a-half later, in the outskirts of Boston, with the famous Battles of Lexington and Concord. By then, April of 1775, the Revolutionary War was underway, a conflict that pitted thirteen united colonies against the British Empire. But how, exactly, had resistance in Boston led to a national revolution?

That critical transformation took place in 1774, in a series of comparatively forgotten events that began in Boston, implicated much of Massachusetts and New England, and garnered support from a much wider swath of would-be Americans. First, there was the so-called “Powder Alarm.” In September of 1774, British troops under General Thomas Gage—the Royally appointed governor of Massachusetts—marched on an armory in Charlestown, just outside of Boston. They seized a stockpile of gunpowder and some other munitions. No shots were fired. Indeed, the British faced no opposition whatsoever.

The rumors New Englanders heard about the British operation, though, were much more dramatic. As news spread, this transformed into a bloodbath. Some heard rumors that a number of Massachussetts men had died defending the powder house, others that Bostonians had been shot down in the street, and others that the British shelled and even destroyed the city. New Englanders would eventually find out these reports were wrong. In the meanwhile, the “fake news” snapped colonists into action.

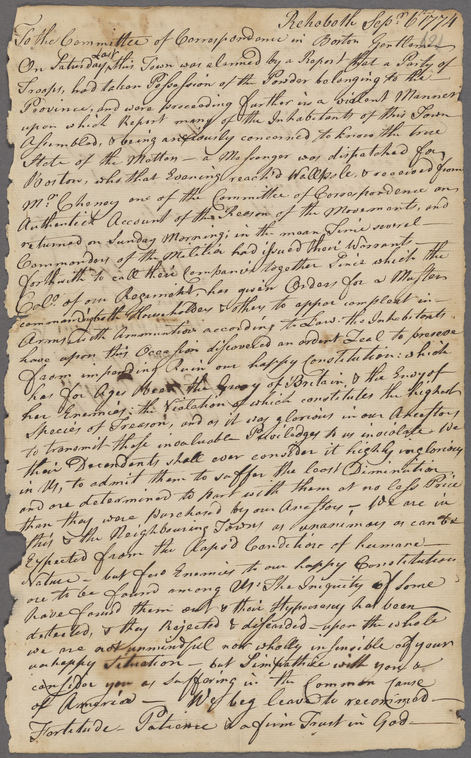

For example, the people of Rehoboth, Massachusetts—a town along the Rhode Island border, and about fifty miles south of Boston--received intelligence that not only had the British “taken Possession of the Powder,” but were also “proceeding further in a violent manner.” As the town gathered more information, “several Commanders of the militia had issued their Warrants forthwith to call their companies together” and prepared to march to Boston’s defense. This story repeated itself across Massachusetts and into neighboring Connecticut and Rhode Island. Over 4,600 militia members mustered in Worcester County, in Central Massachusetts, when they heard the false reports of British aggression.

New England mobilized for war a full seven months before Lexington and Concord. Only there was not yet a war to fight. A few weeks later came the “Suffolk Resolves.” The people of Boston and the rest of Suffolk County issued their nineteen-point list of grievances and resolutions, largely in reaction to the “Coercive Acts.” Passed by Parliament in response to the Tea Party, these laws closed the port of Boston to commerce, all-but-ended self-government in the Bay State, provided that British officials in Massachusetts could be tried outside of the colony in order to secure a “fair trial,” and finally required that colonists everywhere quarter—house—British troops.

The Resolves called for some well-worn methods of resistance, like boycotts of British goods. But they also broke new ground. The Resolves declared that a number of the Coercive Acts were“gross infractions of those rights to which we are justly entitled by the laws of nature, the British constitution, and the charter of the province.” As such, “no obedience is due from this province to either or any part of the acts above-mentioned, but that they be rejected as the attempts of a wicked administration to enslave America.” And Suffolk’s resistance made it clear they could defend themselves with force, if necessary, In effect, the Resolves declared that colonists had a right to decide for themselves what Parliamentary legislation was binding, and what was not. If “no taxation without representation” was a narrow construction of colonists’ ability to stand up to Parliament, the Suffolk Resolves were incredibly broad.

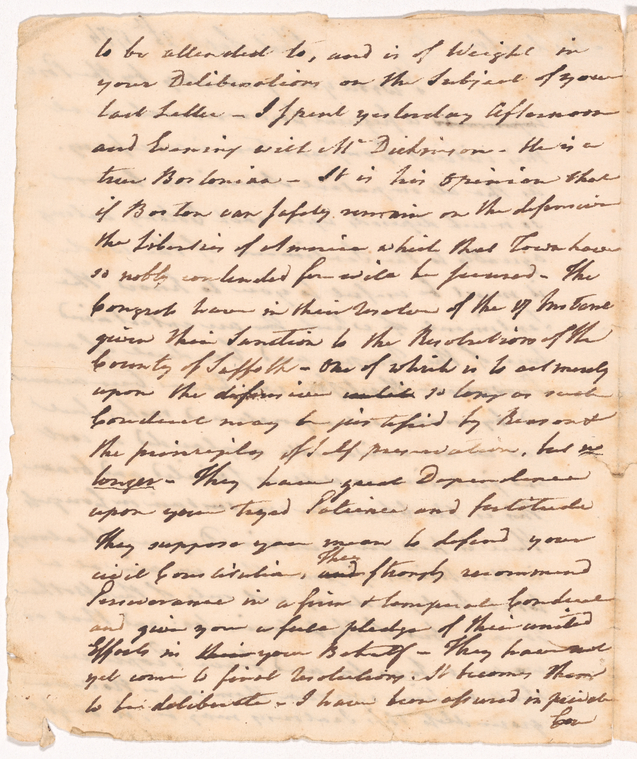

The shocking thing is that the Suffolk Resolves proved widely popular. Colonists saw them as reasonable given British actions over the preceding year. Writing from the Continental Congress, Samuel Adams told Dr. Joseph Warren—a Boston Revolutionary leader—that Congress gave “their sanction to the resolutions of the county of Suffolk.” Adams confirmed that he was “assured, in private conversation with individuals, that, if you should be driven to the necessity of acting in the defence of your lives or liberty, you would be justified by their constituents, and openly supported by all the means in their power.” In September of 1774, Bostonians declared the right to resist Parliamentary actions by force, New England proved it could mobilize for a revolutionary war if necessary, and Congress endorsed it all!

Some of this was not entirely unprecedented. Parts of Massachusetts had already effectively ended British rule earlier in the summer. Residents of Worcester County closed the courthouses, stymying attempts to enforce British law. But the Resolves gave voice to these grievances, couched them in rational political rhetoric, and were public enough to garner support.

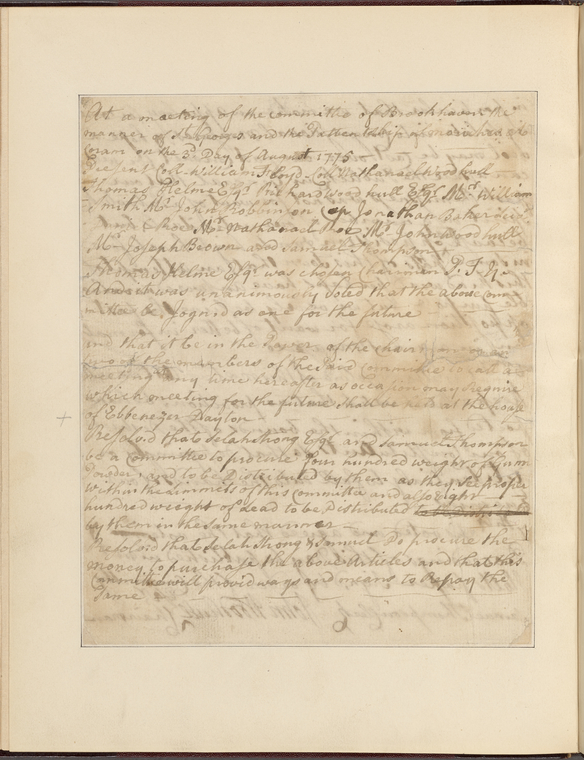

Outside of New England, similar arguments—that the Coercive Acts “are contrary to the Constitution and subversive of our legal rights as English Freemen and British subjects”—justified the ratcheting up of resistance in places like Brookhaven, New York (on Long Island). The Committee of Safety formed there committed to enforcing that the community would “adhere to the Resolutions of the Honorable Continental Congress,” which of course had endorsed the Suffolk Resolves. That Committee of Safety readied the community for war; during a subsequent meeting, the committee authorized members to procure gunpowder.

How a Boston rebellion became an American Revolution is a story too seldom told because it is one we take for granted. It’s a story that recently digitized materials held by The New York Public Library help us to tell.

Further Reading

For more on the critical events of 1774, see Ray Raphael, The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (New York: New Press, 2002); Richard D. Brown, Revolutionary Politics in Massachusetts: The Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Towns, 1772-1774 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970); T.H. Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (New York: Hill & Wang, 2010); John L. Brooke, The Heart of the Commonwealth: Politics and Society in Worcester County, Massachusetts, 1713-1861 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989). On the transition from resistance to Revolution more generally, see Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1972). On the Brookhaven Committee of Safety, see Christopher F. Minty, “'Of One Hart and One Mind': Local Institutions and Allegiance during the American Revolution," Early American Studies 15 (Winter 2017): 99-132.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present on-line for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.