Biblio File

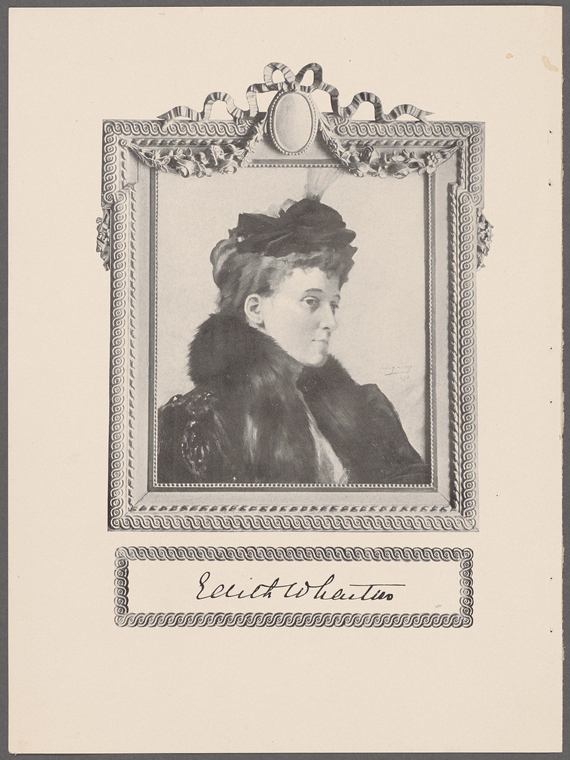

In Defense of Edith Wharton

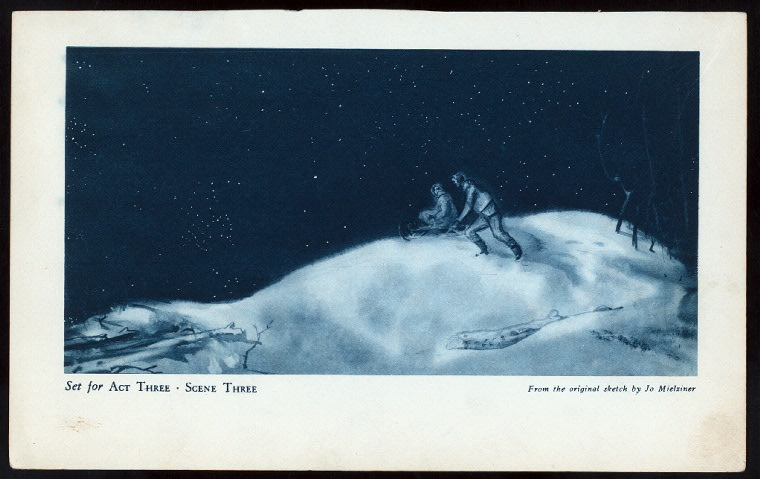

"He seemed a part of the mute melancholy landscape, an incarnation of its frozen woe, with all that was warm and sentient in him fast bound below the surface."

—the preface of Ethan Frome (1911)

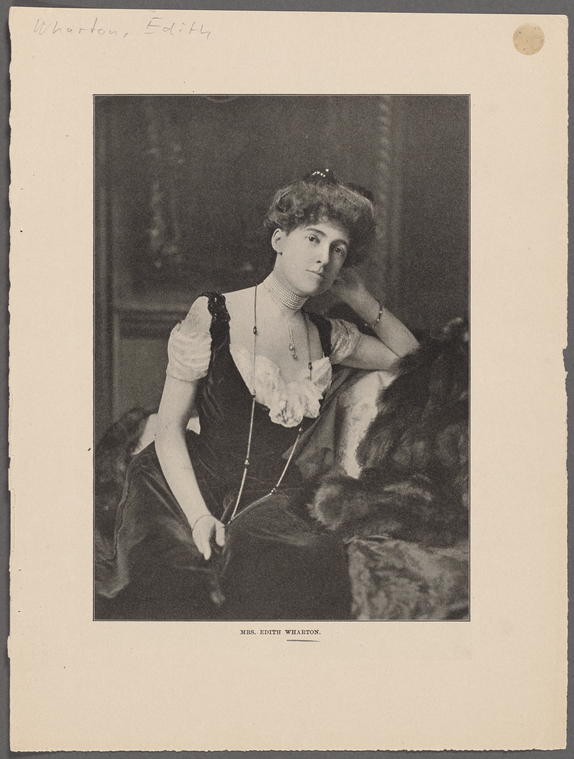

January 24 marks the birthday of a great American writer, Edith Wharton. Writing during the late 19th century into the early 20th century, Wharton is best known by the adaptations of her work — and there have been many.

The most recent, and likely the most well known, are The Age of Innocence, Ethan Frome, and The House of Mirth. Collectively, they star some of Hollywood's biggest stars over time, and one can't help but wonder what brought about a resurgence of interest in Wharton's work in the latter part of the 20th century, almost 100 years after she began writing. To explore that question, we must look at more than just the text, but also at the woman who created such lasting works about life among the wealthy in New York City.

Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones in a townhouse in New York in 1862. Her family was conservative and part of the wealthy society of old New York. Born into a life that expected little more of women than to pursue domestic interests, Edith had bold intellectual desires, but they were not encouraged.

Instead, she received the minimal education necessary — privately tutored, of course — and was pushed to fulfill the societal expectations for a woman of her status, which involved traveling to Europe and living life as a member of the upper class.

During these travels, she befriended writer Henry James, a fateful meeting with the man who would become a good friend and mentor. Encouraged by that relationship but unable to openly pursue her interests, Edith was still an avid reader; in her teens, she began writing poetry and short fiction. Some of the work she produced during that time appeared in well known publications such as Harper's and Atlantic. She even published her first short novel at the age of fifteen under the name David Olivieri, and she would continue writing off and on into her twenties.

After a few failed engagements, Edith was encouraged to marry an older man named Edward Wharton in 1885. A banker, Edward and Edith had little in common other than their respective positions in society. (Literature Resource Center)

Despite having grown up in the same social atmosphere as she'd married into, Edith was unhappy with the life of a society wife traveling, which focused on attending parties and other frivolous activities. Events such as the Light Guard Ball (pictured above) were a common occcurence in late 19th-century New York.

After years of unhappiness, she suffered a nervous breakdown in 1894 and was sent to a sanatorium to recover. Encouraged by doctors to write as a means of improving her condition, she began writing professionally soon after her stay.

By 1907, she lived in Paris full-time with her husband — and shortly after moving, she began a wildly passionate affair with journalist Morton Fullerton. This inspired some of her writing during this time. While the affair didn't last, neither did her marriage. After her husband suffered several breakdowns of his own, and after years of unhappiness, they divorced in 1913.

Wharton saw little reason to return to the United States and only did so sporadically over the last 25 years of her life. She did return to recieve an honorary degree from Yale University in 1923, and she became the first woman to do so. Throughout her life she continued to write and do charitable work in Europe. She died in France and was buried in Versailles. (Biography in Context, Chambers Biographical Dictionary)

I must admit, my initial experience with Edith Wharton was not by choice. I was running a book club at my library branch and would always add at least two classics on the list we would read for the following year. I was familiar with Wharton mostly due to passing knowledge of the film The Age of Innocence, which I had never seen (and would not see until after I read the book).

I'm sometimes reluctant to read a book that is considered a "classic". The truth is, for every brilliant classic, there are quite a few that are hard to read or relate to — and the word is often tossed around in reference to virtually any title written within a certain timeframe, not just those that have earned it. But my first experience with Edith Wharton's writing convinced me that she is one of those rare writers whose work falls firmly into this category.

In The Writing of Fiction, Wharton described the focus of her novels as the conflict between the desire of the individual and the authority of social convention. Wharton constantly revisits this theme, especially in some of her most popular novels. The House of Mirth (1905) is the story of the gradual worldly decline of a society beauty named Lily Bart. She seeks wealth, security, and admiration in various groups of New York society, and, because of a mixture of Fate and her shortcomings (vanity and snobbery among them), is cast out by every class, ending her days in a miserable room, having failed to succeed even as a humble seamstress.

Ethan Frome (1911) explores the sad life of a taciturn yet sensitive man who has lived in a small New England farming town all his life. He marries his cousin Zeena for reasons of expedience, and the loneliness and difficulty of life in the backwoods turns the already unsympathetic character into a bitter hypochondirac. A hired girl enters the picture and turns Ethan's small world upside down. Their brief and chaste, though passionate, romance ultimately leads to tragedy. (Literature Online)

A bit more light-hearted, although no less tragic, The Custom of the Country (1913) provides one of literature's most unlikeable characters in Undine Spragg. Undine is a social upstart from the Midwest who marries New York aristocrat Ralph Marvell, in the hope of social glory. Finding her husband too quiet and not rich enough for her extravagant taste, she seeks excitement with the super-wealthy, divorcing Marvell to pursue a millionaire. This behavior continues throughout the novel, with Undine leaving and pursuing men she believes will help her rise above her station. She has a son whom she often ignores or uses as a bargaining chip against his father. The story is ultimately a dark comedy of manners.

Wharton's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Age of Innocence (1920), is considered by many to be her finest work. Not quite as cynical as some of her other novels, the story concerns the love of New York gentleman Newland Archer for two women — "innocent" all-American May Welland and her cousin, exotic Ellen Olenska, returned from Europe after a failed marriage. Archer is engaged to May but falls in love with Ellen, having first supported "decency" by imploring Ellen not to create scandal by divorcing. By the end of the book, he begs her to release herself, marry him, and proudly eschew the social restrictions placed on them. Ellen and Archer eventually battle against their passion (though they gain no credit; society assumes they have been lovers), she returns to Europe and Archer marries May. (Literature Online)

I enjoy Edith Wharton's writing so much because of its authenticity. Whenever I read one of her stories, I feel as if I have entered another world — except it's one that really existed. It's fun reading about social mores in a different time period while knowing how things play out in modern New York, and finding simple things like the descriptions of parts of New York City that I know well, but at the time were entirely different or didn't even exist.

For example: The New York Public Library's flagship location on 42nd Street and 5th Avenue wasn't completed until 1911, a decade after Wharton's first full novel. I remember some descriptions in The Age of Innoncence of characters living in upper Manhattan and how those areas were practically wilderness, only just being built up at that time, so the rich would often build mansions there because of the space. There's something to be said for experiencing history as it was happening. For Edith, this was her world. She knew it inside and out and was able to create engaging stories centered on this life, which she seemed to both loathe and be fascinated by.

That juxtaposition certainly had a hand in her story telling. Reading and writing stories was something she had been doing since a young age so it seems her critical eye was turned, likely fairly early, to those around her. In doing so it would have meant she was also keenly aware of her role among the elite. Her stories are often about outsiders, whether it's a woman trying to join the wealthy and find a better place in society or people who can't pursue the lives they want because they're bound by the restrictions of their positions.

As an outsider herself, Wharton was all too familiar with having ones path layed out for them whether they wanted to follow it or not. Yet we know she didn't shy away from certain aspects that her family's wealth afforded her, including a world-class education, extensive travel, and a lavish lifestyle. Her position as an insider/outsider gave her a unique perspective to offer readers in a manner that was engaging and accessible.

In celebrating Edith Wharton's life, I wholeheartedly recommend reading her work. Much of it still has a vibrancy in its depictions and story-telling. Her writing, while rooted in a time long gone, survives because it is simply very well done. You don't have to be a New Yorker to enjoy it, and you don't have to be a history buff — you just need to appreciate good writing with a bit of angst mixed in.

---

Have trouble reading standard print? Many of these titles are available in formats for patrons with print disabilities.

Staff picks are chosen by NYPL staff members and are not intended to be comprehensive lists. We'd love to hear your ideas too, so leave a comment and tell us what you’d recommend. And check out our Staff Picks browse tool for more recommendations!

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.