The Specter of Foreign Influence in Early American Politics

In his farewell address, George Washington famously cautioned Americans against both “the baneful effects of the spirit of party,” or partisanship, and the “insidious wiles of foreign influence,” which Washington decried as “the most baneful foes of republican government.” Washington was not trying to predict future problems. Beginning even before Washington’s presidency, the intertwining of global trade and diplomacy shaped domestic politics and partisanship in the United States in ways that many Americans found alarming. Washington could do little to halt this tendency.

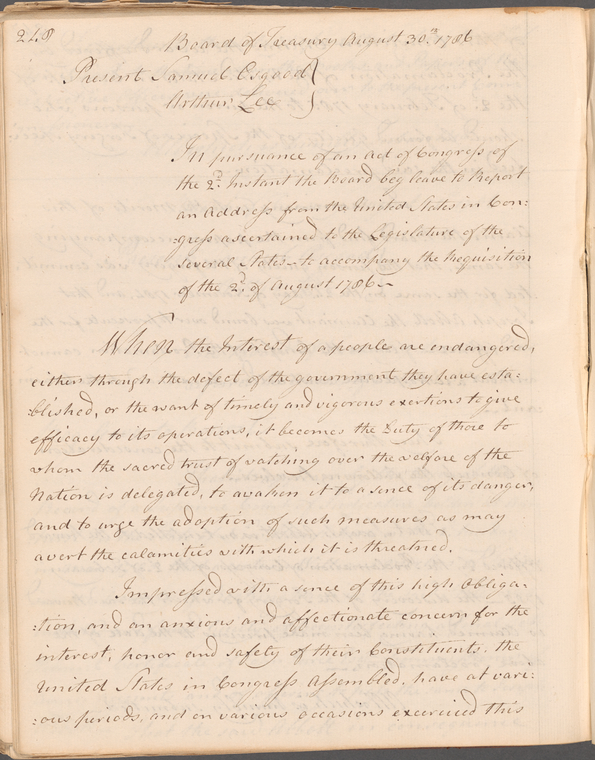

Before Alexander Hamilton served as the first Secretary of the Treasury, before even there was a Treasury department or a Constitution for that matter, the United States Congress created a Board of Treasury to manage the nation’s finances. In a 1786 report to the state legislatures, the Board sounded the alarm about the United States’ financial situation. The nation had racked up debts to European creditors in order to pay for the Revolutionary War, but did not have the revenue to pay it off. Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress could only request funds from the states, which retained the power to tax. The Board of Treasury believed it was their “duty ... to awaken it to a sense of its danger and to urge the adoption of such measures as may avert the calamities with which it is threatened.” Despite the looming threat of angry European creditors, the states proved unable to agree on reforms to the national financial system.

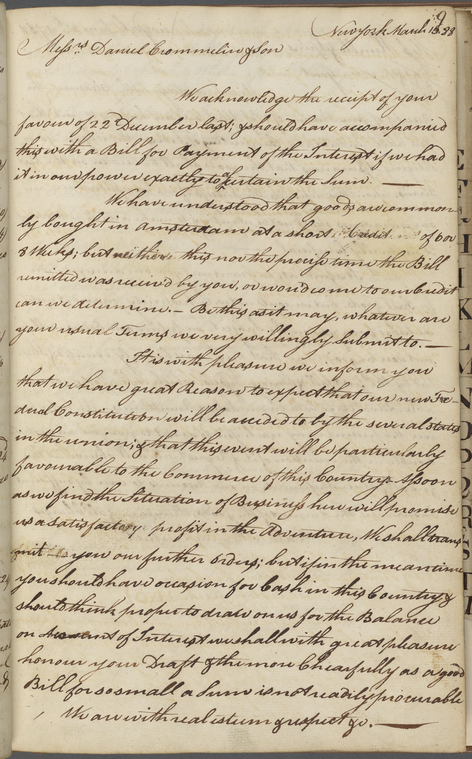

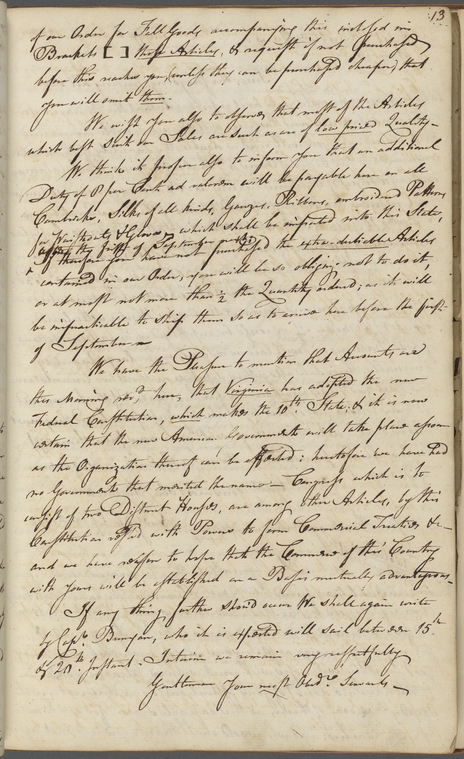

But the United States Constitution, drafted a year later, aimed in part to address just these sorts of concerns about the United States’ financial relationship with Europe. For one thing, it gave Congress the power to lay and collect taxes, a significant transfer of authority from the states to the national government. If we are to believe certain merchants, by strengthening the central government in this way, the Constitution also might have altered the future of American involvement in global trade, and the United States’ relationships with European nations. People like the New York merchant Lewis Ogden both followed the debate over ratification and kept their European trading partners apprised of the situation. Writing to business associates in London, Ogden opined that the new governing charter “will be particularly favourable to the commerce of this country.”

A few months later, shortly after Virginia became the tenth state to ratify the constitution in July 1788, Ogden informed his colleagues that it was “now certain the new American government will take place.” This left him optimistic that “the Commerce of this country with yours on a Basis mutually advantageous.” American entanglements abroad influenced both the framing and the ratification of the Constitution.

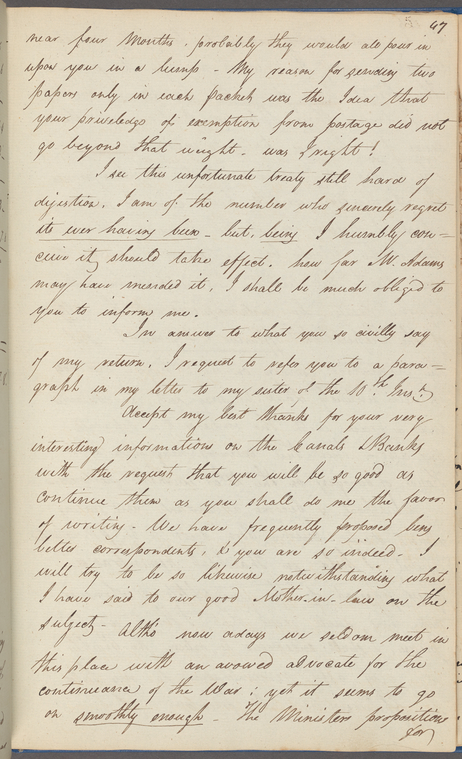

Foreign commerce continued to shape American domestic politics. In 1795, the United States and Great Britain signed a commercial treaty known as the Jay Treaty (named for John Jay, the American negotiator). Negotiated and adopted in the midst of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Treaty was a flashpoint in the United States’ increasingly vitriolic partisan politics, which pitted pro-British Federalists against Jeffersonian Republicans, sympathetic to France’s revolutionary struggle. Writing from Liverpool, the American merchant and Consul (in this period, consuls were not professional bureaucrats), James Maury noted that “I see this unfortunate treaty still hard of digestion” back home. In fact, he shared many Americans’ disdain for the treaty; he “severely regret[ted] its ever having been.” Maury, nevertheless, “humbly conceive[d] it should take effect.” The world simply looked different from his perch in England than in his home state of Virginia, where opposition ran rampant.

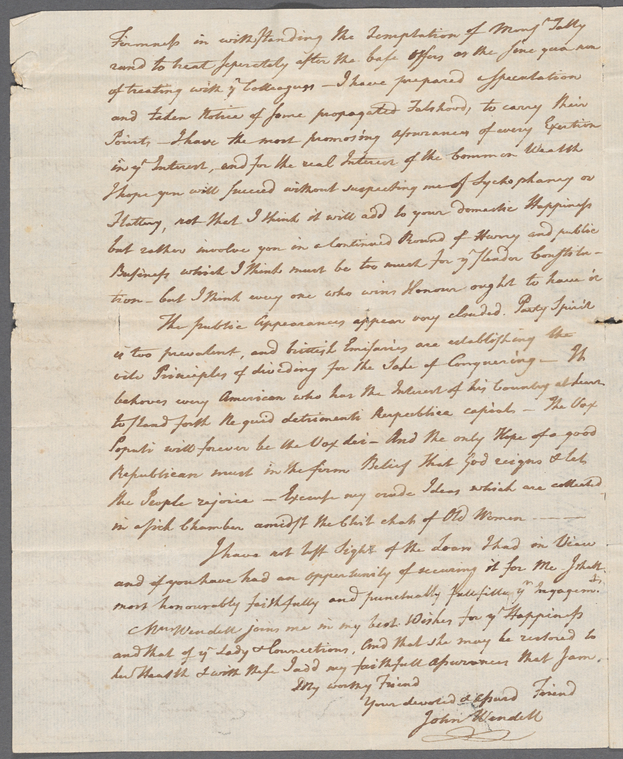

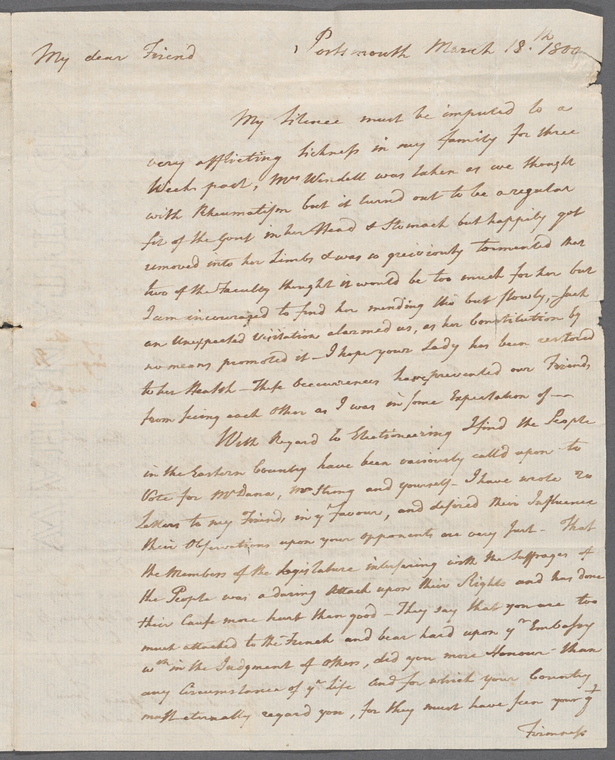

Foreign affairs affected local elections as well. Elbridge Gerry—the namesake of gerrymandering—had served on an ill-fated diplomatic mission to France in 1797. When it became clear that France had no intention of negotiating, Gerry’s co-envoys left, but he stayed behind. This haunted Gerry during his failed run for the Massachusetts governorship in 1800. One friend informed Gerry that his opponents “say that you are too much attached to the French.” He sensed something more nefarious afoot. “Party spirit is too persistent,” Gerry’s friend proclaimed. He went so far as to suggest that “british emissaries are establishing the vile principles of dividing for the sake of conquering.” Hyperbolic as this rhetoric appears, that it seemed possible that British officials might attempt to influence a Massachusetts gubernatorial election, meant that Washington’s fears were close to being realized.

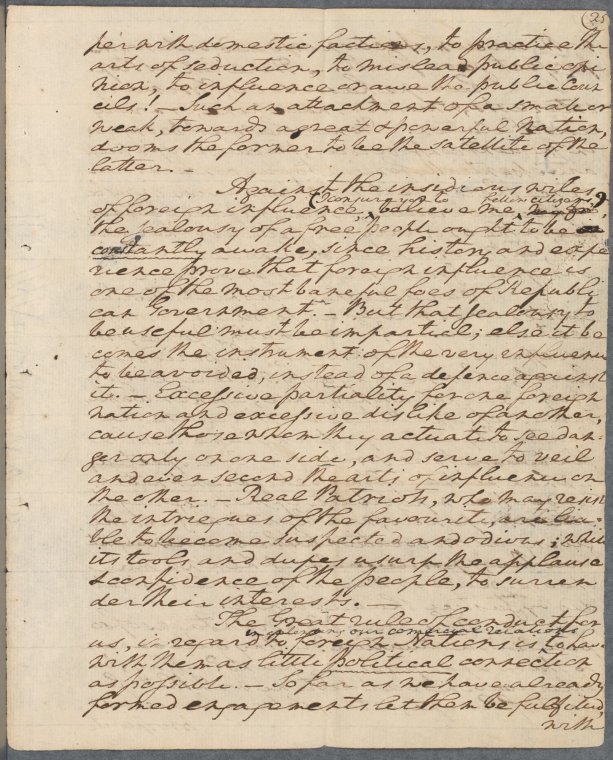

Washington not only thought partisanship and foreign influence were “baneful,” but that the two were interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Partisanship, he wrote, “opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions.” Twenty years after the heady summer of 1776, independence seemed, somehow, still precarious. Perhaps because Washington raised concerns about these “baneful” tendencies, fears about how foreign intrigues might influence domestic politics outlive him. Indeed, this remains a stubbornly potent rhetorical trope in American political culture.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present online for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.