Which Witch Is Which? The Other Salem/McCarthy Parable

For my last blog post before retirement, I am pleased to feature the research and analysis of Emma Winter Zeig, volunteer and former intern, on one of the songs discovered for "Laughter, Agita and Rage": Political Cabaret in Isaiah Sheffer's New York. The archival collections let us discover and match up lyrics with piano and piano-vocal scores, which we were able to date and annotate using the paper and electronic references resources, such as indexed newspaper and periodical data bases.

October is one of the few times of the year when users of the phrase “witch-hunt” are actually referring to a search for witches. Usually, witch-hunts are reserved for decidedly non-supernatural people or ideas. Many Americans learn about the idea of a modern witch-hunt at the same time as they learn the story of Salem, America’s most famous literal witch-hunt, by reading Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. However, Miller was not the only one to see the similarities between the 20th and 17th century witch-hunts. While researching the exhibit "Laughter, Agita, and Rage”: Political Cabaret in Isaiah Sheffer’s New York, currently at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, I reviewed some of the political songs in the Jay Gorney Scores, including one called “Riding the Broom.” The piano-vocal score for “Riding the Broom” is on view, along with other examples of political songwriting by both of its authors: the composer Jay Gorney and the lyricist Lewis Allan. Written in 1947, a whole six years before The Crucible, “Riding the Broom” contrasts America’s witch-hunt for Communists with its witch-hunt for witches. What it lacks in John Proctor, it more than makes up for in J. Parnell Thomas.

Saying that “Riding the Broom” is unpublished makes it sound better known than it actually is. A Google search for “Riding the Broom” and the name of either songwriter will elicit exactly two results, both archival records from nypl.org referring to the artifact currently on display. Though the song was little known, I did not find it by accident. Jay Gorney and Lewis Allan were both politically outspoken in their songs, so I knew that Gorney’s collection would contain material useful to the exhibit. In this respect the library finding aid was particularly helpful to me, since it allowed me to see that many of Gorney’s “Historic and Progressive” songs were grouped in one sub-series. Jay Gorney often used progressive social issues in his writing; his most famous composition, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” expressed the unease that society could not take care of the people who put in the work to build it, but “Riding the Broom” may have been closer to home. Gorney wasn’t called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) until 1953, but by 1947 the FBI was already investigating him. This was one of the other reasons that I was specifically interested in Gorney and in “Riding the Broom.” I had been looking to expand the McCarthy Era coverage of “Laughter, Agita, and Rage” and, knowing Gorney’s history, the title of “Riding the Broom” and that everything else in its sub-series was either during or close to the McCarthy Era, I suspected that the song would be a good prospect for exhibition even before I first saw it. After his hearing with HUAC Gorney was blacklisted, but his son remembered that, at least in the beginning, it was hard to break Gorney’s faith in the people’s goodwill and the power of theater. He mounted an updated revival of his 1930s show Meet the People where he wrote new political parody songs that satirized HUAC, including one called “Are You Now Or Have You Ever Been?” His son Daniel remembered Gorney explaining “When the American people learn the truth, they will not put up with what’s going on. They will do the right thing.” Though public opinion did turn on HUAC, Gorney never reached the heights of his pre-hearing career.

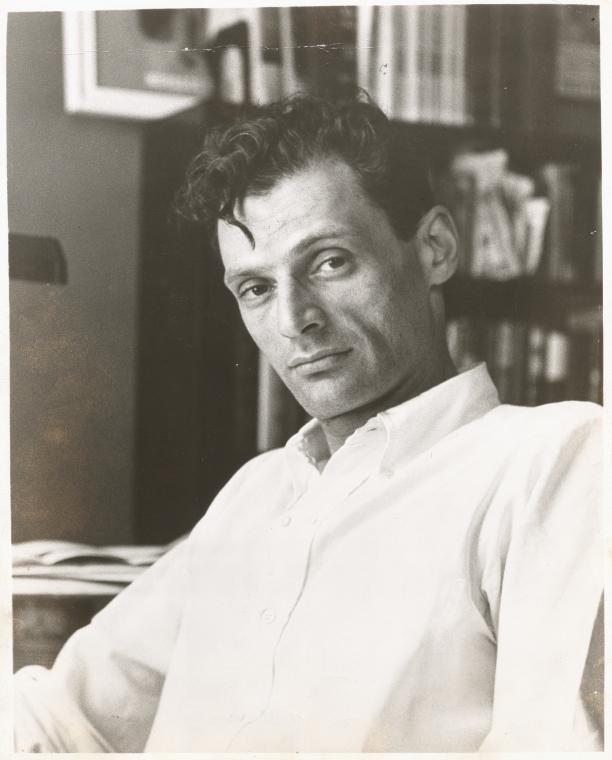

Lewis Allan had a long career and was credited on such famous songs as “The House I Live In"and "Strange Fruit”. It would be hard, however, to sum up Allan’s personal life, since he did not have one. Lewis Allan was a pseudonym created by an English teacher named Abel Meeropol. Left-leaning politically, Meeropol wrote songs that championed causes such as the rights of workers and the struggle against Franco in Spain. Often he brought humor to his criticisms of society, such as with his anti-appeasement tune “The Chamberlain Crawl,” which included the phrase: “Oh you start out in British style/ But you end up with a ‘Heil.’” “Riding the Broom” fits into Meeropol’s larger pattern of songs with a political message and a humorous bent, but the subject was ever more person because though he was not blacklisted, he was investigated by the Rapp-Coudert Committee (a committee questioning leftist tendencies among teachers) in 1940. He could have had even more of a motivation to write about this subject in 1947 because of mounting pressure on Communists in Hollywood at that time. Allan had just gotten recognition for Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “The House I Live In,” but hopes for a major career in films were cut short by suspicions about his political beliefs. The United States’ investigation of Communism also had implications for Meeropol’s personal life after he wrote “Riding the Broom,” since in the 1950s, he and his wife adopted Robert and Michael, the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

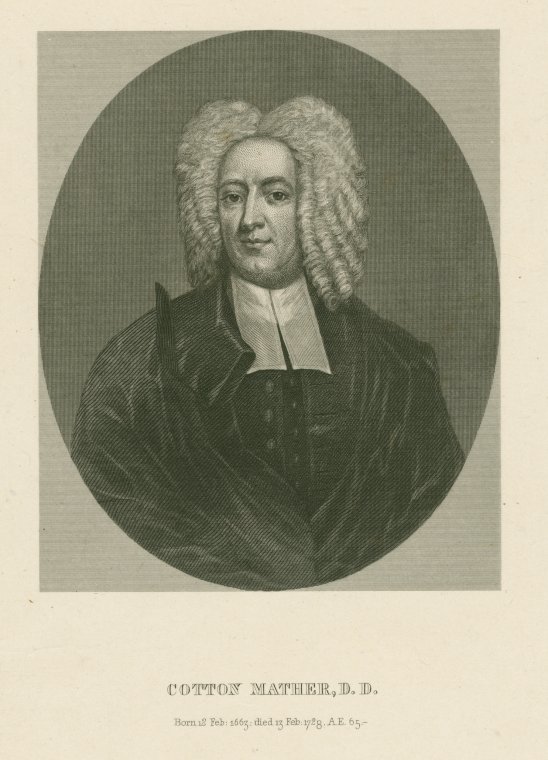

Once I had found “Riding the Broom,” I was struck by its political argument, as well as the spritely and humorous tone with which it was delivered. I did research on the song’s background using electronic resources like ProQuest, available through nypl.org, and showed the artifact to exhibit’s curator, Barbara Cohen-Stratyner. We both agreed that it would be an excellent candidate for “Laughter, Agita, and Rage.” That said, I understood why the song has stayed in the shadows for all of these years. Though it makes a strident argument that the 1950s restrictions on political thought were hearkening back to a more conservative time, it could have been difficult for the song to reach a wide audience because of its structure. Broadly speaking, the first verse takes place in Puritan New England, and the second and third verses in modern times. However, half of the first verse is an impersonal narrator speaking in the third person, and the other half is an imagined quote from Cotton Mather in the second person. The song then segues into the chorus, which is no longer Mather speaking, but is still in the second person. The second verse is entirely the narrator’s voice, but is half in the first person and half in the second person. The third verse is entirely in the first person, but that is because it is supposed to be in the character of J. Parnell Thomas, chairman of HUAC, a fact that is not indicated in the song, but rather by a note in the sheet music. While these frequent changes in character and verbal style might have been relatively easy to convey in a performance setting, where multiple performers or other visual cues could be used, the structure of the song would hamper its ability to be a hit on the radio.

“Riding the Broom” makes use of the same metaphor as The Crucible, but to a very different effect. Meeropol and Gorney saw the Salem Witch Trials through their own personal lens—not Miller’s lesson in hysteria, but a lesson in the perils of a repressive society. “Riding the Broom” opens with a picture of life in 17th century Salem: “It was sinful to go bowling tho’ smiling faces might be seen that yearned to dance on the village green. No one dared to go May-Poling. Or their heads would soon be rolling.” It is worth noting both that no one was beheaded during the Salem Witch Trials, and that none of the accused’s supposed crimes were bowling-related, but it tells the listener a lot about Meeropol that the great crime he assigns to the Puritans is stifling freedom of expression (this is not an unfair charge, but is not usually the first complaint about a time when people were being executed based on “spectral evidence”). Like Miller, Meeropol was motivated by what he saw happening in the 20th century. Miller watched former friends name names and wrote about the conflicting and dubious motivations of the judges, accusers, and the accused in the 17th century. Meeropol saw artists being punished for their beliefs and for what they wrote, and imagined Cotton Mather telling an audience “You’re going to hell ‘cause you’re starting to think.” When Meeropol brings his song into the 20th century, he makes his point about freedom of speech even more explicit by citing the First Amendment, saying “The witching hour is here again and couples meet…all a-flutter all a-tremble. Is it legal to assemble?” Meeropol looked back at Puritan New England and saw a society where expression was demonized, not one where citizens were assembling to accuse their neighbors of consorting with demons, so that is what he wrote.

Meeropol’s world is free of The Crucible's hysteria; in its place is the cool certainty of a domineering government. In “Riding the Broom” there are no accusers in Salem, and no one names names in HUAC. Instead, there are authority figures who hand down unquestioning and immediate judgment. In the first verse, the narrator explains “If someone questioned…Cotton Mather would reply: ‘The Devil’s got you deep inside you’ve given Old Satan a chance to hide.” In other words, the supposed witches in the Salem of “Riding the Broom” would reveal themselves to their accuser. It is the same case in J. Parnell Thomas’s verse, with Thomas singing, “I know sub-ver-sives by their look…You’ve dared to think and think out loud you’re causing a riot by getting a crowd.” Thomas identifies his “subversives” as people who “think out loud,” “caus[e] a riot,” and “[get] a crowd,” all very public behaviors. He also states that he knows them “by their look,” which is an internal process inside his own mind. This implies that the Thomas of the song has no informants and is questioning people he either believes to have Communist tendencies because of his own preconceptions of what a Communist looks like, or because those people have identified themselves to him in some way. Thomas’s assertion that he can identify Communists on sight also implies a degree of certainty that would be out of place in The Crucible, where some of the judges seem more concerned with making the trials seem justified than making sure justice is served.

Meeropol’s attitude in the song makes complete sense. Meeropol’s son Robert remembered a story about a meeting that Meeropol attended where he was given Communist literature, but, though he agreed with the cause, he did not really feel like reading the dense books. He said “I know who our friends are. I know who our enemies are. Isn’t that enough?” In 1947, when much of the more shocking testimony was still to come, it is easy to think that Meeropol could continue to make such a clear delineation between friend and enemy, and conclude that it was more likely for the government to assign guilt to the most public figures than for supposed friends to turn on each other.

Sources

Gorney, Daniel. “Commie Kiddie-Porn Days Gone By,” Cinema Journal 44 no. 1 (2005): 90-96.

Kovaleff Baker, Nancy. “Abel Meeropol (a.k.a. Lewis Allan): political commentator and social conscience,” American Music 20, no. 1 (2002): 25.

Newstead, David Michael, “Strange Fruit and Abel Meeropol.” Philosophy of Shaving, August 22, 2016, https://philosophyofshaving.wordpress.com/2016/08/22/strange-fruit-and-abel-meeropol/.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.