Drinking Whiskey in the Whiskey Rebellion: The Soldiers' Perspective

An overwhelming sense of déjà vu probably washed over the western Pennsylvania countryside in 1794. Less than twenty years after revolting against British tax policies that they deemed unfair, Pennsylvania farmers found themselves opposing another unwanted tax imposed by a distant central authority. In 1791, on the urging of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, the new national government passed an excise tax on distilled spirits. When the government moved to enforce the law, many small farmers who produced whiskey on the side rose up to oppose it. Before too long, Pennsylvania farmers stared down the barrels of guns held by their new countrymen.

The federal government won the day and suppressed the whiskey rebellion. Hamilton and his Federalist allies believed they had restored order. Discontented western farmers felt that tyranny triumphed and that their country had forsaken its Revolutionary principles. Both groups could agree that this conflict revealed the full power and reach of the new national government. The 13,000-man militia that Hamilton and George Washington amassed to put down the rebellion, though, probably found the government’s power wanting.

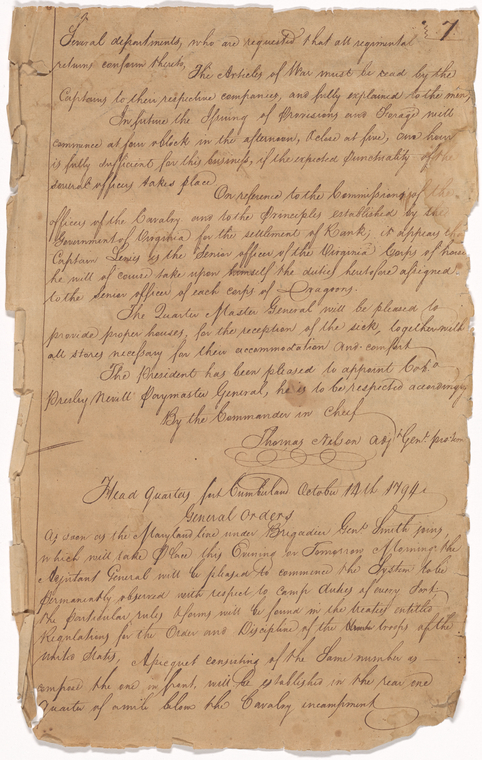

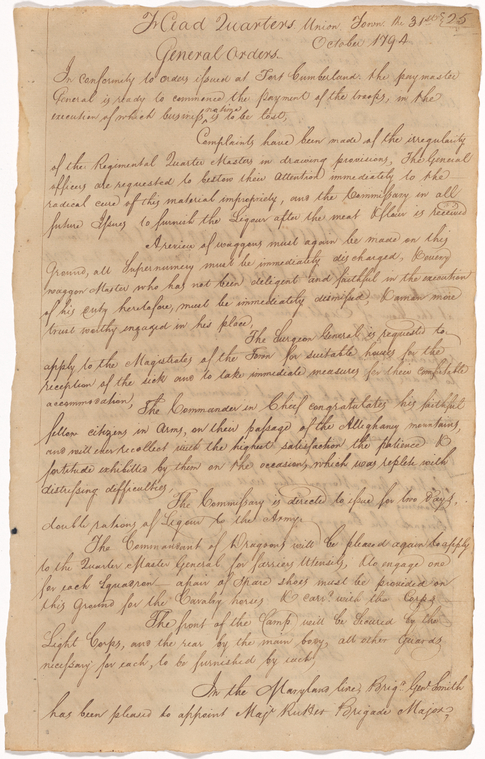

Included in NYPL’s recently-digitized Liebmann collection of American historical documents relating to spiritous liquors, is an orderly book that documents the experience of the Virginia militia called out during the Whiskey Rebellion. These soldiers did not have it so easy.

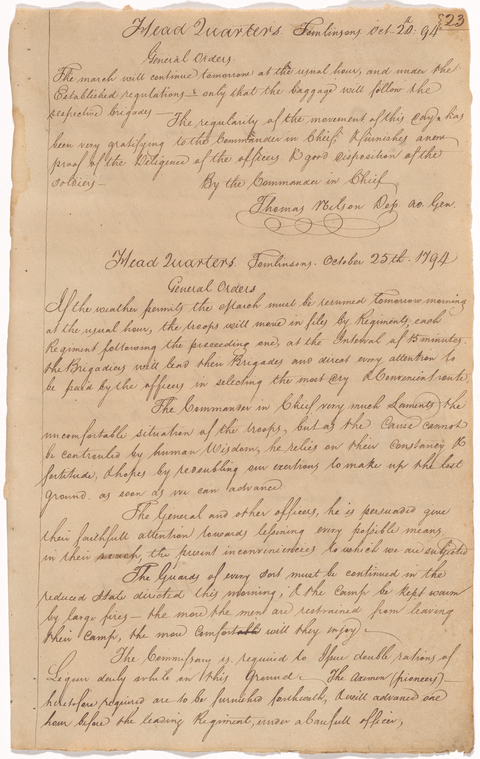

On October 25, 1794, “The Commander in Chief" expressed that he "very much laments the uncomfortable situation of the troops.” The Army found it difficult to supply consistently this massive force, especially as it moved further west and away from commercial centers along the eastern seaboard.

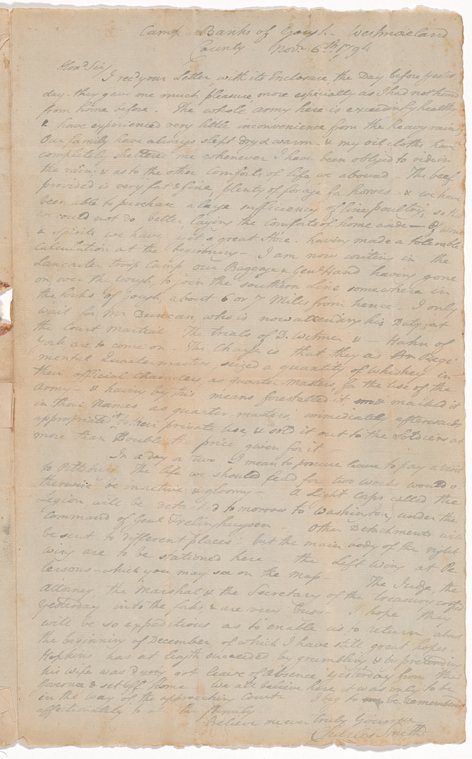

While the troops remained at the mercy of overburdened supply lines, many officers could afford to supplement their provisions. Charles Smith, for one, lived large. Writing to Jasper Yeates—Smith’s father-in-law, and a Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court who would eventually negotiate an end to the Rebellion—Smith noted that “as to the other comforts of life, we abound—The beef provided is very fat & fine, plenty of forage for horses & we have been able to purchase a large sufficiency of fine poultry; so that we could not do better, laying the comforts of home aside—Of wine & spirits we have yet a great store, having made a tolerable calculation a the beginning.” He wrote this from the “Lancaster troop camp.”

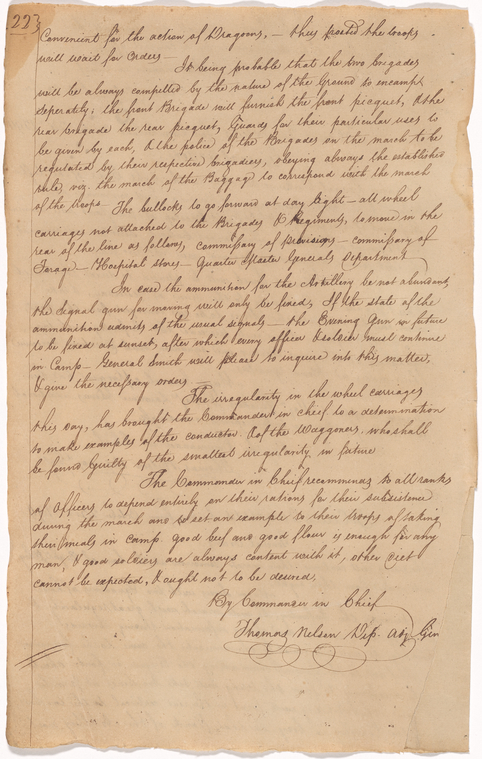

Class disparities could deepen enlisted men's discontent and threaten the Army’s unity. During one march, “The Commander in Chief recommend[ed] to all ranks of officers, to depend entirely on their rations for their subsistence during the march and to set an example to their troops of taking their meals in camp.” By urging the officers not to eat off menu, Washington probably hoped both to ease tensions within the Army and keep the troops from foraging.

Many troops were also probably somewhat skeptical of their mission. The 1791 excise tax hit rural people the hardest. Many farmers in the west distilled whiskey because it was the easiest way they could convert their surplus corn into a less perishable form, and therefore get it to market. Small distillers claimed that the tax severely cut into their already limited profits. Nor could they pass the tax on to consumers by baking it into the price, as most merchants did with imported goods. Western consumers would likely not pay, and large eastern distillers could undercut the price. Indeed, the law taxed small operations at an effectively higher rate than it did large distilleries run by merchants in the east. The tax was regressive, and it burdened people with whom many troops probably identified

Ironically, liquor was often the solution to dissent in the ranks. On a number of occasions, the troops received “double rations of liquor” to quell their dissent. Whiskey sustained the force sent to put down the whiskey rebellion.

The whole conflict was probably unnecessary. For the first three years of the new federal government’s existence (1789-1791), customs duties (taxes on imported goods) accounted for about 99.5% of federal tax revenues. Hamilton suggested the excise on distilled spirits to generate extra revenue that would help make up for an anticipated shortfall in funds to service the national debt. He also wanted to diversify the federal government’s revenue streams and excise taxes were a mainstay of European fiscal regimes. In England, excise taxes often accounted for upward of 40% of the central government’s revenue. But that was precisely the problem.

Excise taxes galled Americans because they smacked of English tyranny. Hamilton knew this. He had argued in Federalist 12 that the United States would and should survive chiefly on import duties. “In most parts of” the country, he wrote, “excises must be confined within a narrow compass.” This was because “excises, in their true signification, are too little in unison with the feelings of the people, to admit of great use being made of that mode of taxation; nor, indeed, in the States where almost the sole employment is agriculture.” For all the trouble, excise taxes added very little to federal coffers. Excluding proceeds from the sale of public lands, over 90% federal revenues before 1836 came from customs duties.

Hamilton and Washington’s great show of state power depended on the threat of military force. The experience of the troops in that military force suggests, though, that American state power rested on a shakier foundation than Hamilton, Washington, and their political allies might have wanted to admit.

Further Reading:

On the Whiskey Rebellion, see Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); and William Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion : George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels who Challenged America's Newfound Sovereignty (New York: Scribner, 2006). On American government finance and tax policies more generally, see Gautham Rao, National Duties : Custom Houses and the Making of the American State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); and Max M. Edling, A Hercules in the Cradle : War, Money, and the American State, 1783-1867 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present online for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.