A Brief Passage in U.S. Immigration History

Population Movements

Political trends prove that a not insignificant number of people in the United States believe that an “American” is one who finds tradition and bloodline in a single indigenous ethnicity bound to a longstanding, native region. But even the flightiest peep into the slimmest textbook on U.S. history demonstrates otherwise, and one will perceive that America, like most inhabited places on the planet, and moreso, is the result of the happenstance of population movements. To alienate those people once called "aliens" is alien to the inalienable right of foreign-born citizenship-seekers.

Tribes of Delaware Indians who once inhabited Brotherton Reservation in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, soon removed to regions in the Midwest; British convicts auctioned off in the colonies of New England; southern Italians to Argentina before 1888, the year an economic crisis redirected immigrants from the Mezzogiorno to Brazil and the States; Oklahoma "sooners" stampeding into Indian Territory in 1889, when Congress, under the Homestead Act, opened lands north of Texas which had formerly been settled by displaced Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole tribes; African-Americans in Florida who gained freedom after the Civil War but decamped for Northern states after the election of 1876, when Republicans withdrew federal protections in former slave states; or New York Irish families who left Hudson Street on the West Side of Manhattan to make the epic journey across the Hudson River and resettle in Hudson County, New Jersey; these are examples of population movements, some major and some minor.

Between 1565, when Spanish settlers founded St. Augustine in Florida, understood as the oldest continuously settled city in the United States, and 1815, at the end of the War of 1812, the second war between America and Great Britain, the majority of the roughly one million migrants to what would become the United States were from the British Isles, Germany, and Africa. Africans were the largest ethnic group, with an estimated 360,000 crossing as slaves in this time period, where one in five slaves died during passage. Roughly 325,000 Europeans arrived as indentured servants seeking eventual free status, or as convicts expelled by the British government. These numbers are ballpark figures, and reflect a study of 1790 census data published in the William and Mary Quarterly in 1984, and an analysis by genealogists in The Source (2006).

The first U.S. census was taken by 650 federal marshals in 1790, and enumerated the population at 3.9 million, which is about equal to the borough of Manhattan plus Queens. The majority of people were U.S. born. Tribal nations were not included in the U.S. census until 1880, because Native Americans were not legally citizens of the U.S., unobliged to pay taxes and withheld the right to vote.

By 1783, at the end of the Revolutionary War, some colonists could trace a family history in America back five to seven generations, with roots in a handful of different countries. From 1790 to 1815, about 5,000 immigrants arrived in the U.S. each year.

Passenger Lists

Familiarity with the history of immigration in the U.S. can provide context for immigration resources used in genealogy research, and as an aid for locating records, knowing whether or not records might exist, where they might be, and what sort of information they might yield. U.S. immigration laws have changed numerous times, continue to change, and are sometimes prevented from changing; these processes alter the types of records accorded to evolving procedures. Changing policies also reflect the shift in contemporary political and social attitudes about newcomers settling in America, which often collide like super-velocity beams in a particle accelerator.

There are numerous records that might trace or prove the details and facts of population movements, that map demographics, place individuals at a certain date, or provide statistical data. One of the most heavily used resources of this type are ship passenger lists. Passenger lists, also called ship manifests, show all the passengers on a vessel traveling to or from the United States, and depending on the year, will provide a varying amount of genealogical data about the passenger, as well as information about the ship. Passenger lists are the chief source of information for researchers of immigrants to the United States between 1820 and the 1950s.

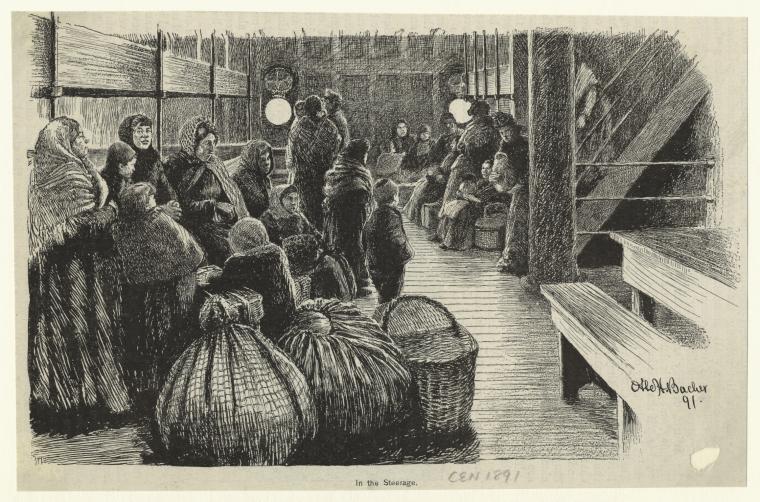

Most records of transatlantic passengers in the colonial period are lost, or were never kept in the first place. Immigration and citizenship laws were decided by each individual colony. Passenger list records are accessible today because of federal laws seeking to monitor incoming residence-seekers in the United States, which laws were first instituted in 1820 with the Steerage Act, a benchmark immigration law that required ship captains to keep official passenger lists of vessels sailing to American ports. The lists would be periodically furnished to the Secretary of State. It was the first law to regulate passenger vessels and monitor individuals arriving in the country. But it was marginally enforced. The avarice of ship captains often resulted in overcrowding and debased conditions on the ship, and in 1840, Congress passed a series of laws to regulate tonnage-to-passenger ratios in order to control the number of people allowed on board.

The Steerage Act served as the boilerplate for future immigration laws related to ships and vessels. The act was named after the area in the ship designed for cargo but loaded with people who could not afford cabin class. In this manner, the ship, which had originally departed the U.S. with goods like cotton or lumber to trade in overseas ports, would capitalize on the empty space for the return trip home.

A copy of the passenger list was handed to state processing officials at the port of entry and filed with the Collector of Customs. Officially known as “Customs Passenger Lists” (1820-c.1891), the forms were not standardized, but generally included the ship’s name, ship’s master or captain, port of embarkation, date and port of arrival, and the name, age, sex, occupation, and nationality of the passenger. In addition, any deaths that occurred at sea were noted in the pages following the lists.

Naturalization Papers

The next most useful resources in U.S. immigration research are naturalization papers. Naturalization is the process one is required to undergo to become a citizen of the United States. A naturalization often consists of a series of official documents that include valuable genealogical information.

Naturalization is a two-step procedure. Generally, a Declaration of Intention (or First Papers) was made after two years of residency in the U.S. Second or Final Papers, in the form of a Petition, were filed after an additional three years residency. Filed in court and signed off by a judge, an oath of allegiance was taken, a certificate of citizenship issued, and the individual officially transpatriated as an American.

In colonial America, citizenship was mandated by the individual colonies. Under British rule, newcoming white males often took an oath of allegiance in order to legally exercise the right to own property. From March 26, 1790, when Congress passed the first Naturalization Act, to September 26, 1906, when the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization was founded, a naturalization could take place in a number of local courts, and sometimes at the federal level.

The early laws required an initial two years residency. This was extended to five years, for qualified applicants who were “free white persons of good moral character.” In 1798, during a period of intense paranoia of foreign influence, especially French, the Alien and Sedition Acts were passed, stretching the residency requirement to 14 years. The Acts reflected a feud between Anglophile Federalists and Jeffersonian, Francophile Democratic-Republicans. The Act was little enforced except for the totalitarian Sedition laws, which resulted in the imprisonment of numerous publishers, editors and writers who voiced or printed anti-Federalist sentiment in public forums.

In 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment protected, with some qualifications, “all persons born in the United States” as citizens; African-Americans could naturalize after 1870, while Native American naturalization was restricted in 1887.

In the nineteenth century, many immigrants could live viably as an American without becoming a citizen; harassment and prejudice might have been common, but not the threat of deportation. For example, between 1890 and 1930, the U.S. census shows that 26 percent of aliens were never naturalized. After 1906, all naturalizations were processed at the federal level.

All racial restrictions were lifted in the 1952 Immigration and Naturalization Act, and since 1992, the naturalization process is no longer handled or filed in courts.

Castle Garden (1855-1890)

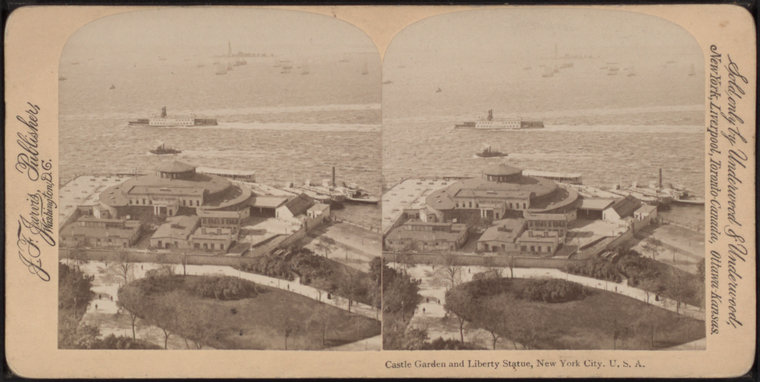

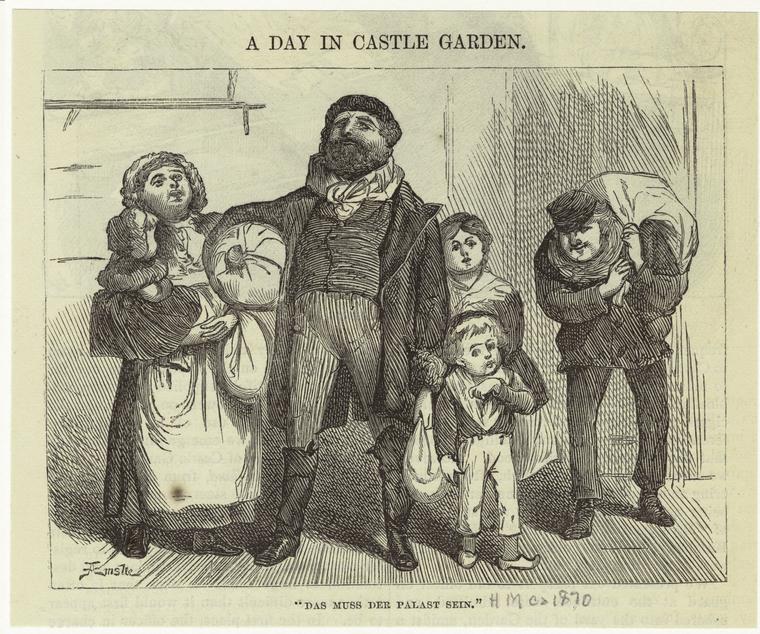

The first immigration center in the U.S. was known as Castle Garden, a former fort during the War of 1812 that was converted into as an amusement hall and public resort in the 1820s, at the southwest edge of Battery Park. A point of maritime disembarkation as well as a major New York City tourist attraction and public event space, the grounds were then leased by New York City to the State’s Board of Commissioners of Emigration.

The experience of the immigrant, or “alien,” arriving at Castle Garden began at the Quarantine Station, six miles south of Manhattan in New York Bay, where healthy passengers were separated from the sick.

At the Emigrant Landing Depot, Customs agents collected fees and the NYPD inspected luggage before the immigrant entered Castle Garden and proceeded to the Registering Department. Here, an agent recorded names, nationality, former residence, and intended destination. Like all the records related to Castle Garden, these records are lost.

Before the establishment of Castle Garden, an industry of abuse and exploitation thrived at the port areas where immigrants disembarked. No protection had existed for newcomers, who were often greeted by thieves, con artists, hoodwinkers, and thugs. Tickets would be sold for transport that did not exist, luggage was stolen, and human traffickers posed as good samaritans. When Castle Garden opened, the government provided authorized railroad agents to vend transportation; a supervised baggage delivery service to transport luggage; a reliable currency exchange to buck criminally high rates; an Information Department that put newcomers in touch with waiting friends or family and any waiting letters or funds; licensed and approved boarding house keepers who solicited immigrants with no housing; and a Labor Exchange to offer sound, temporary employment.

Ellis Island (1892-1954)

Formerly known as Oyster Island, where Delaware tribes collected shellfish in New York Bay, Ellis Island was the first federal immigration processing station in America. Originally a cavernous three-story building made of wood, the building burned down in 1897 and reopened in a brick and iron structure three years later. An average of 10,000 people were processed each day, and one time, at its peak in 1907, the center bulged with 21,000 individuals in a single day.

Revised immigration laws in 1924 introduced the requirement of first obtaining a visa at the U.S. Embassy located in the country of origin, which process drastically reduced the staff and traffic at the immigration stations at U.S. ports. Passengers continued to disembark at Ellis Island after its processing station closed, after a total number of immigrants estimated at twelve million. The building shut in 1954 and was put under the auspices of the National Park Service in 1965. Occupied by Native American and African American activists as a locale to assemble and demonstrate in the 1970s, it was not opened to the visiting public as an historic site until 1990. Besides Liberty Island, it is the only terrestrial border between New York City and New Jersey, where one can walk from one realm to the other without crossing a bridge.

U.S. Immigration History

Between 1820-1840, seventy percent of immigrants were German, Irish, or English. Immigration from Germany in particular spiked between 1847 and 1855, with a combination of political upheaval, crop failures, and an increasing scarcity of land unfit to accommodate the rising population.

Irish immigration to the U.S. from Ulster County spiked in the early 1770s on the eve of the Revolutionary War. Irish passengers to America in the years of the early republic was the result of a handful of economic factors, like high taxes, currency manipulation, skyrocketing farm rents, and low crop prices. Though this era pre-dated the Steerage Act, indexes of Irish arrivals in America have been published that draw from passenger lists which appeared in Irish newspapers, notably The Shamrock, or Hibernian Chronicle.

The next major Irish wave was the result of the infamous potato famine, which appeared by dubious origins as a splotchy white fungus in 1845, and continued to ruin the normally high yielding potato crop which a many farmers relied on for livelihood. The famine continued through 1848, while the farm economy of Ireland depended very little, if at all, on other or alternative crops. In 1845, the population of the country was about 8.5 million. In 1851, because of starvation, disease, and migration, the population plummeted to 6.5 million people.

During a brief, inflammatory period of months in 1848, mass uprisings by the working class against monarchial regimes ignited across Central and Western Europe. The famous revolution of 1848, the same year gold was discovered in California, was brief, forceful, and, as the historian Eric Hobsbawm said, “within six months of its outbreak, its universal defeat was safely predictable.”

When oppressor regimes were soon reinstated, much of the disenfranchised laboring and peasant classes had cause to flee, spurring immigration to the U.S., a nation where the government had only recently formed as a result of revolution, and which appeared to disavow social class and promise democratic voice to all citizens, in addition to an equal process of citizenship to aliens.

There was an old Italian anecdote about the immigrant en route to America, expecting streets paved with gold, who learns three things upon arrival. “The streets weren’t paved with gold; they weren’t paved at all; and I was expected to pave them.”

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusionary Act banned Chinese women and children from entering the country and restricted males to diplomats, students, and businessmen.

After the 1881 assassination of Czar Alexander II in Russia, government retaliation inaugurated a series of pogroms against Jewish populations in the Ukraine and Bessarabia, today Moldova. This was followed by laws discriminating against Jewish land ownership, known as the May Laws. Major flight of Russian Jews characterized the 1880s and 1890s. In all, about 2.3 million people from the Russian Empire migrated to the United States between 1871 and 1910—among them Lithuanians, Poles, Latvians, Finns, and Ukrainians. A bulk of these migrants sailed to the U.S. from the ports in Hamburg or Bremen.

In Italy, a migration boom occurred roughly between 1871, ten years after the Unification of Northern and Southern Italy, and 1915, when a German submarine attacked and sank the Lusitania, a British ocean liner, sparking the United States to eventually enter World War I. A bulk of migrants left the south of Italy, known as the Mezzogiorno, where by the 1880s birth rates were high while death rates were falling. Between 1880 and 1887, Argentina was the prime destination for immigrants from the Mezzogiorno; from 1888 to 1897, it was Brazil; and after 1898, the United States, which in the early twentieth century was the landing place for 65 percent of all Italians leaving Italy.

In addition, in 1908 an earthquake in Southern Italy triggered a forty foot tsunami that decimated Calabria and coastal Sicily, with the death toll reaching up to 80,000 people. Many displaced survivors departed for the United States.

One hundred and one U.S. ports were in operation throughout the nineteenth century. Pacific coast passenger list arrivals were recorded beginning in 1850. In 1895, the U.S. initiated the collection of records that tallied and processed border crossings of individuals arriving from Canada, and in 1903, immigrants from Mexico into California, Texas, New Mexico, or Arizona. 1907 marked the official year that an act was passed to record alien arrivals at U.S. land borders, or “contiguous territory.” These records took the form of “card manifests” listing identifying information.

In the decades after the Civil War, the U.S. government expanded. The Department of Justice was founded, Civil Rights acts were passed in the 1870s, and enforcement of voting policies was conducted by U.S. marshals and federal election officials. Likewise, in 1890, the Treasury Department terminated its contract with the New York State Commissioners of Emigration, and a year later the federal government assumed total control of all U.S. immigration operations. Consequently, between 1893 and 1907, the number of columns of personal information on passenger lists rose from five to twenty-nine. “Aliens” were now asked how much money they carried; to provide the address of relatives or contacts in the U.S. they were meeting; and if they were an anarchist or polygamist.

With the exception of Irish Catholics, the majority of immigrants before 1882 were Protestants from Northern and Western Europe. By 1907, three out of four immigrants were Catholics and Jews from Southern and Eastern Europe.

The 1924 Immigration Act passed by Congress targeted specific nationalities with quota restrictions. The number of newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europeans nations allowed into the U.S. would now be limited to 2% of the total number of people from those origin countries listed in the 1890 United States census. For example, if one million individuals were listed in the 1890 federal census as born in Italy, then only 20,000 Italians would be allowed entry into the United States annually after 1924.

The 1930s were characterized by more departures from the U.S. than arrivals, while quota laws, World War II, internment camps, and the suppression of ethnicities of wartime enemies were some of the factors causing levels of immigration to decrease.

In 1933, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was established, as part of the Department of Labor; it would later be transferred to the authority of the Department of Justice, which oversaw immigration until 2002 when the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) created the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Recent naturalization records are now only obtainable through a Freedom of Information Act request.

While the government reevaluated Alien Registration laws during the Cold War, Congress continued to make it law to keep passenger manifests, including for aircraft; however, arrival records furnished to INS officers were no longer submitted to the collections of the National Archives. As a result, the bulk of lists that may have been kept after the late 1950s are not accessible to researchers.

In 2014, President Obama had announced a series of Immigration Executive Actions, which by various measures provided “temporary legal status to millions of illegal immigrants,” and an “an indefinite reprieve from deportation.” One of these actions would have extended and expanded the “Deferred Action to Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents,” (DAPA) which the DHS describes as an “administrative mechanism” that helps eligible immigrants without legal status to gain “work-authorization… pay taxes and contribute to the economy." Challenged in federal court by 26 states, an injunction was imposed against DAPA by a U.S. District Court in Texas. When the case reached the Supreme Court, in June 2016, the judges deadlocked, and the injunction was “affirmed by an equally divided court.” As a result, the “unauthorized immigrant population” affected by the outcome was estimated by the New York Times at roughly six million people.

The Ellis Island of America in 2016 is Los Angeles International Airport, where arrivals are greeted by the Theme Building, a work of unique architecture resembling a futuristic spacecraft, and co-designed by a former Hollywood art director.

Bibliography

The Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History, and Genealogy offers free public classes on passenger list research and researching naturalization records.

NYPL Immigrant Services helps non-English speaking and other immigrants understand and interact with the culture, government, and educational system of the United States.

Passenger Lists

- They Came In Ships: A Guide To Finding Your Immigrant Ancestor's Arrival Record / Colletta.

- Mass Migration Under Sail / Cohn.

- American Passenger Arrival Records / Tepper.

- Passenger and Immigration Lists Index / Filby. Full volume set in Room 121.

- New World Immigrants / Tepper. 2 vols.

- A Bibliography of Ship Passenger Lists, 1538-1825 / compiled H. Lancour; rev. R. J. Wolfe.

Castle Garden & Ellis Island

- Encountering Ellis Island / Bayor.

- American Passage: The History of Ellis Island / Cannato.

- Encyclopedia of Ellis Island / Moreno.

- Castle Garden as an Immigrant Depot, 1855-1890 / Svejda.

History of Immigration

- Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives / Eales and Kvasnicka.

- Prologue | Journal of the National Archives. Available online & NYPL Room 121.

- U.S. Immigration and Migration Almanac / Benson & Hermsen.

- Immigrants in the Far West: historical identities and experiences / Embry & Cannon.

- Transforming America: Perspectives on U.S. Immigration / LeMay.

- Daily life in immigrant America, 1820-1870 / Bergquist.

- Daily life in immigrant America, 1870-1920 / Alexander.

- Population History of New York City / Rosenwaike.

- Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Department of Homeland Security.

- “The European Ancestry of the United States Population, 1790: A Symposium.” / Purvis. The William and Mary Quarterly; vol. 41, no. 1 . Jan. 1984.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.