Anahid Ajemian: In Memoriam

The violinist Anahid Ajemian, who dedicated her artistic life to performing and fostering new music, died on June 13, 2016. She was a child of Armenian immigrants. Her parents (Levon Ajemian, a doctor, and Siroon Erganian, a pianist and music teacher) were living in Switzerland in the early 1920s. Their first child, Maro, was born in 1922, and not long afterward the family moved to New York City. There, Dr. Ajemian resumed his medical practice and his wife taught piano; her students included Maro. Anahid was born in 1924, and recalled a musical household, not only because of her mother and sister:

Although my father wasn’t a musician, I always heard him singing—especially sharagans, chant-like Armenian hymns. As with many foreign families in America, we were close and our ethnic roots were evident in family gatherings and social events.

Anahid demonstrated a strong interest in music from an early age. “I always wanted to be a violinist,” she remembered later. “There was never a doubt in my mind.” As a child, she began studying at the Institute of Musical Art (later the Juilliard School), where her sister had been attending since the age of 6. Her main instructor was the violinist Edouard Dethier; she also studied chamber music with violinist Hans Letz and the cellist Felix Salmon, and performed with the Juilliard Graduate School Orchestra under Albert Stoessel.

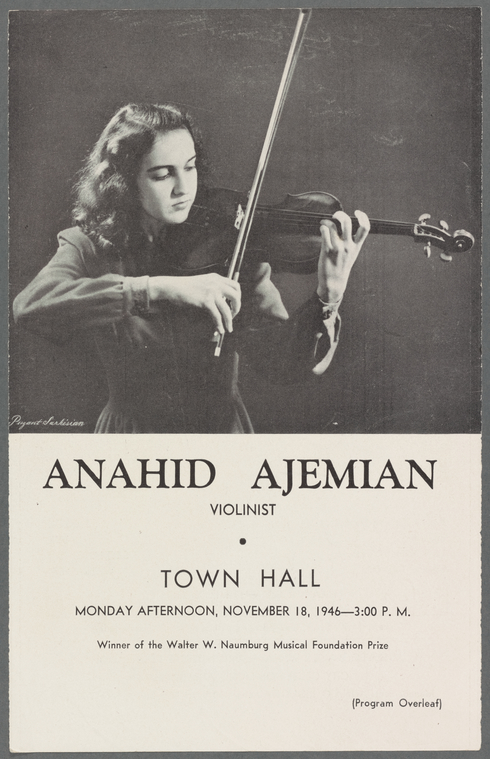

In 1946, Ajemian won the Walter W. Naumburg Foundation competition, a prestigious honor. In November of that year, she made her solo recital debut at Town Hall, and soon commenced performing in a duo with her sister. Maro Ajemian’s career was already well-established by that time: she debuted at Town Hall in 1940, and performed the U.S. premiere of Aram Khachaturian’s Piano Concerto in D-flat Major, Op. 38, with the Juilliard Orchestra, in 1942. She was already concentrating on contemporary works, and had been performing the music of an unknown composer of Armenian descent by the name of Alan Hovhaness.

Anahid Ajemian was also interested in new music, and the sisters seemed set on a mission. One composer led to another, and within a few years, they had ties to John Cage, Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, Ben Weber, Ernst Krenek, and Wallingford Reigger. Among the pieces written for Anahid and Maro Ajemian (together or as soloists) were Hovhaness’s Suite for Violin; Cowell’s Set of Five for Violin, Piano, and Percussion; Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano; Carlos Surinach’s Doppio Concertino for Violin, Piano, and Orchestra; Krenek’s Double Concerto for Violin, Piano, and Orchestra; and Harrison’s Suite for Violin, Piano, and Orchestra. The Ajemians made premiere recordings of several of these works.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, the sisters toured the United States, Canada, and Europe, earning strong reviews from critics and audiences. They received the American Composers Alliance Laurel Leaf Award in 1952 (they were the first musicians to receive the honor), and in 1964, they were the first to perform the complete Beethoven Sonatas for violin and piano on television (KQED in San Francisco, for the National Educational Television Network).

In 1965, Anahid Ajemian took on a new project: The composer, conductor, and scholar Gunther Schuller asked her and violinist Matthew Raimondi to assemble a string quartet to premiere a program of new quartets by four young American composers at Carnegie Recital Hall. They recruited violist Bernard Zaslav and cellist Seymour Barab, and dubbed themselves the Composers String Quartet (CSQ). Schuller later commented that “the Composers String Quartet was the first systematic effort by a top-notch string quartet to not only find good new works, but to learn and perform them in such a way that the composer himself would be completely satisfied.” (In 2014, when Seymour Barab died, Ajemian wrote a remembrance of him for New Music Box.)

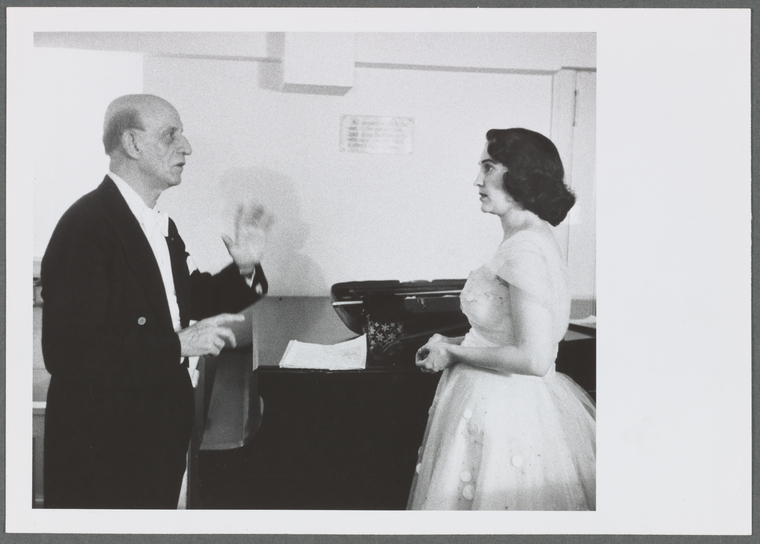

The group rapidly gained renown for its performances and its fostering of new music: it created a biennial competition to encourage the creation of new works for string quartet, and produced recordings of many of the prize-winning compositions. Over the course of 30-plus years, the CSQ performed and/or premiered works by Milton Babbitt, David Baker, Samuel Barber, Jack Beeson, John Cage, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Henry Cowell, Ruth Crawford, David Diamond, Donald Harris, Bernard Hoffer, Charles Ives, Ernst Krenek, Lawrence Moss, George Perle, Mel Powell, Gunther Schuller, Elliott Schwartz, Roger Sessions, Ralph Shapey, and Morton Subotnick, among many others. The CSQ’s relationship with Elliott Carter was particularly fruitful. It was one of the first to perform his string quartets on a regular basis, and it recorded them as well, garnering rave reviews and a Grammy nomination.

The quartet also toured the world, sometimes sponsored by the U.S. State Department, and performed in countries such as China, India, and Sierra Leone, where no string quartet had ever performed before.

Anahid Ajemian’s partnership with her sister sadly ended with Maro’s death in 1978. The CSQ remained active into the 1990s, and Ajemian continued to perform and teach on the faculty of Columbia University into the early 2000s. In 1984, she was inducted into the Order of the Knights of Malta, a humanitarian honor that took note of her artistry, pedagogy, and service to the Armenian community. His Holiness Garegin II, the Catholicos of all Armenians, honored Ajemian with an encyclical in 2008, citing her accomplishments and prominent role in the Armenian diaspora.

Anahid Ajemian’s full, remarkable career is all the more notable considering the three children she raised to adulthood with her husband, George Avakian, in a marriage that flourished for 68 years.

“Music for Moderns”: The Partnership of George Avakian and Anahid Ajemian, is dedicated to the memory of Anahid Ajemian.

All quotations are from biographies or press releases in the George Avakian and Anahid Ajemian papers, JPB 14-28. Music Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.