Romantic Interests: Digital Middlemarch in Parts

George Eliot’s most famous novel, Middlemarch, is set at the end of the British Romantic era, a time of great social and political upheaval. The novel explores the lives of a network of ordinary people—residents of the fictional town of Middlemarch, in provincial England.

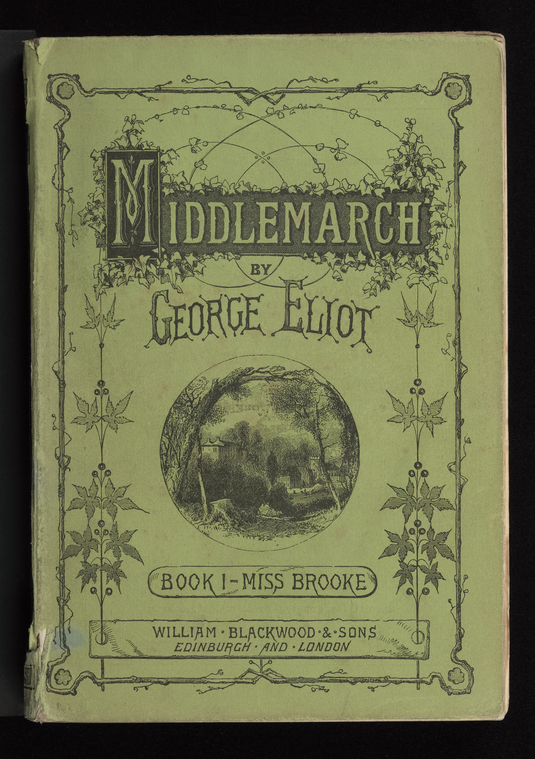

Middlemarch was first published in parts, that is, in eight paper-bound volumes coming out at two-monthly intervals, between 1871 and 1872. The Pforzheimer Collection holds two copies of this first edition, one of which has recently been digitized and made available in NYPL’s Digital Collections. I sat down with Dr. Simon Reader, a professor at CUNY Staten Island, to talk about Middlemarch, and the implications of this first edition appearing in digital format.

What is the significance of Eliot setting Middlemarch at the end of the Romantic era?

It actually has as much to do with the period in which she wrote it as the period in which she set it. Middlemarch is set during the years leading up to the First Reform Act [passed in 1832], which was, to put it in the simplest terms, the first major attempt in Britain to expand voting rights to a larger segment of the male population. Eliot was writing the book at the time of the Second Reform Act [passed in 1867]—another period of major social strife and conflict, when even more individuals from diverse social classes were being enfranchised. She was responding to tensions in her own time by representing the tensions from forty years before.

The subtitle of Middlemarch—“A Study of Provincial Life”—seems to be a direct description of her project and her method: an almost scientific examination the everyday. Was this approach to fiction avant garde at the time?

Certainly. Eliot was one of the first major English novelists to be concerned with representing reality as it was, in a kind of documentary fashion, as unadorned as possible. English Realism had already existed earlier in the century with Jane Austen, as well as Thackeray, although he’s dubiously realistic, and Dickens—again, kind of realistic, kind of not. Eliot really held herself back from introducing any kind of overly romantic, or sensational, or supernatural elements into her fiction. At the end of Middlemarch, she gives what could be construed as a thesis statement, saying “the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” She’s trying to elevate everyday life, to elevate the life of the common person in all of their hidden obscurity, to magnify the value of small, ordinary actions.

How might a scholar’s or a student’s experience of Middlemarch in this format differ from reading it in, say, paperback form?

Well, this is the digital version of the multi-volume first edition of Middlemarch, which brings us closer to the original article, while at the same time, we’re interfacing with it through a screen—it’s this remediated thing—so it’s at once more and less authentic at the same time, which is interesting. The most obvious difference with the multi-volume version is that it’s in little books. Also, compared to modern editions of Middlemarch, each page has very few words on it. It looks much more like a normal novel [laughs]...

The margins are big, the typeface is large...

Yes, and there are only four or five small paragraphs on each page. Middlemarch is usually presented as this monumental edifice of a work. It’s gigantic, it’s one of the longest major novels in English—and normally it’s this really thick doorstop of a book with words like “grand achievement” pasted all over it. It’s one of those novels that people have to work the courage up to begin, but this version makes it seem a lot less daunting. It creates a different demand on readerly attention. It also reminds us that while today we approach the book as this difficult masterpiece of nineteenth century literature, for readers in its own day it would be something that you might stuff into your coat pocket and read on a Sunday afternoon.

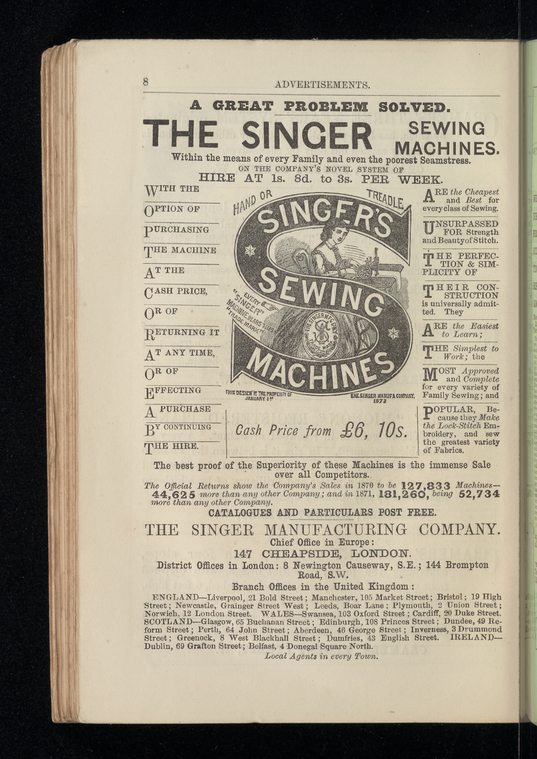

How does the presence of the original advertisements affect the experience of reading Middlemarch?

I like to think of the ads in these volumes as barnacles on the side of this great whale—these little tidbits that you get along with the great big animal, all these little indices of other things. One of the things that the ads tell us about is the readership, the target audience of the book. There are advertisements for other books, of course, but also for things like sewing machines and cocoa and other domestic products— which suggests that women were being targeted as a major audience for the novel, which of course they were. Women read novels, and women also did the shopping, or at least directed servants to do the shopping. You also get to see other charming things: one ad is for something called the “Patent Literary Machine,” which might sound to us like some kind of proto-digital device, but it was actually just a book stand—for readers whose hands or arms or body were compromised in some way, or if they were just too lazy to hold the book themselves. There are strange little ads like that in all these books.

As a professor, how might you imagine using this digital version in teaching Middlemarch?

It would be interesting to have students read at least one or two of the volumes online in this form and then to reflect on the experience. The question would be not what is it like to read it in its original form, but what is it like to read it in its original form which has been remediated by the digital. It could be a springboard for talking about mediation in general—how does the form of our reading materials change the experience or meaning of works? It could also be interesting, maybe in a year-long class, to assign one book of Middlemarch every two months, interspersed with other readings, so they could get a sense of what it would have been like to read the novel as it was issued, not all in one sitting (not that you would ever read Middlemarch in one sitting).

Teaching all of Middlemarch is a huge challenge, so another nice option made available by these digital texts would be to assign only Book 1, and then get students to discuss where they think the novel is going. This gives them the option to keep reading if they want. You might also get them to make some new advertisement for the novel, perhaps by researching everyday products that were available around 1870 and then writing up a rationale for why the ad should be included in the book. Since there are no editorial annotations in this version, you could also ask students to annotate a page or two of the work, especially those sections rich in external references and allusions, or that refer to social issues of the time. The separate volumes also make it clear that Eliot divided her books into these eight parts, so on a simple level showing it to them in this form could spur discussions about what she was doing there. What, after all, is a “book” in the sense that it’s being used here, as a section of an even bigger novel? What’s the relationship between a “chapter” and a “book” in this sense? Do any of the books follow a similar pattern? How do they echo one another? Which ones hold up on their own?

The Pforzheimer Collection also holds first editions of George Eliot's six other novels: Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1863), Felix Holt (1866), and Daniel Deronda (1876); as well as a collection of manuscript notebooks she used while writing Daniel Deronda.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.