British Soldiers' Theatre During the Revolutionary War

A guest post on the research that informed the earliest material in Shakespeare's Star Turn in America, by volunteer (and former intern) Emma Winter Zeig.

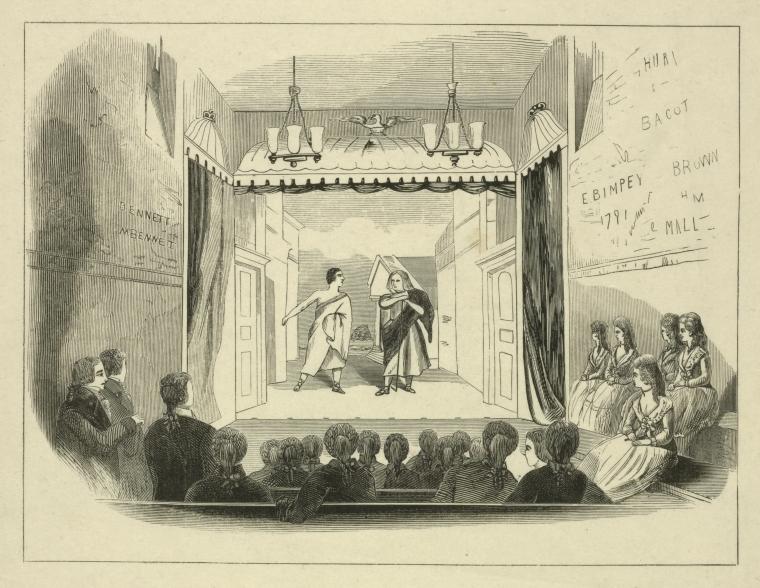

When Shakespeare wrote “All the World’s a Stage,” he probably wasn’t thinking that his words would someday be performed in an occupied city by an invading army. Nevertheless, during the American Revolution, theater seemed to spring up in the oddest of places, often in productions acted by soldiers. The American army attempted a few performances, but it was the British army that seemed to have a firm grasp on the wartime theatrical process.

As the army occupied Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City, they used their time as an invading power to set up theaters. Advertisements for their productions can be seen in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ current exhibition, Shakespeare’s Star Turn in America, as obtained from the library’s electronic resources, particularly America’s Historical Newspapers.

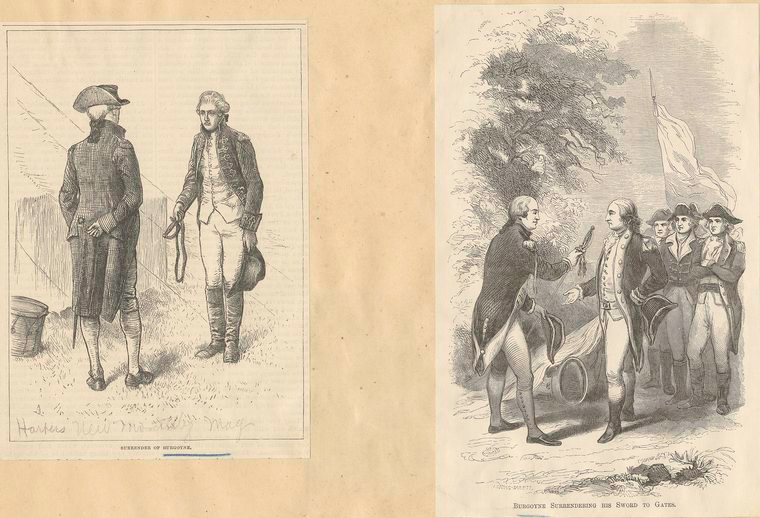

The military theatrical companies were under the command of three men, General John Burgoyne in Boston, General William Howe in Philadelphia, and General Henry Clinton in New York, but there were officers who acted in more than one location. One of the most famous men of the company, Major John André, was active in both Philadelphia and New York. However, he may have confined his Philadelphia activities to painting an elaborate stage backdrop. It ended up outliving him, as he was executed by the Continental Army, and the backdrop stayed in the Southwark Theatre until that theater burned down in 1821.

The military’s performances in Boston were the briefest, but they were the most political. While in Boston, Burgoyne penned an attack on his American foes in the form of a farce entitled The Boston Blockade. The play’s George Washington was “an uncouth figure, awkward in gait, wearing a large wig and a rusty sword.” A handbill was printed entitled “A Vaudevil Sung by the Characters…of a new Farce, called the Boston Blockade,” which contains a threat to the American Whigs, saying “Ye…yanktied Prigs,/ Who are Tyrants in Custom, yet call yourselves Whigs;/ In return for the Favours you’ve lavished on me,/ May I see you all hanged upon Liberty Tree.” The word “Tyrant” is referring to the Puritan attitude towards theater, but it encapsulates their political displeasure with a “Tyrant” America, which they no longer regarded as entirely British, even if they were fighting to keep it a part of the empire.

In Philadelphia, the Thespians staged their biggest piece of political theater. The event, called the Meschianza, was an elaborate farewell for General Howe as he departed the city. Major André designed a party around a joust between two fictional houses: the Burning Mountain and the Blended Rose. The ladies of each house were selected from within the city and the Knights were drawn from the soldiers’ ranks. There was more than a hint of British supremacy, since the outdoor decorations included a “large triumphant arch in honor to Lord Howe.” Though some party attendees lamented that they would never see the like of the Meschianza again, the extravagance in wartime was widely viewed as wasteful and callous. Elizabeth Drinker, whose family had leaned loyalist in the past, condemned the event, remarking “How insensible do these people appear, while our land is so greatly desolated, and death and sore destruction has overtaken and impends so many.”

In New York, the company seemed, for the most part, to be developing themselves artistically. The military thespians had sporadically produced Shakespeare before, but in New York, they produced multiple performances of six plays by Shakespeare. This seems like a choice made partially for prestige reasons because even though comedies and farces were more popular with audiences, the company chose only one comedy, and five of Shakespeare’s dramas. Though they never produced a completely original play, the New York company also started to write original material more regularly in the form of prologues given before select performances.

The prologues contained many instances of pro-British flattery, such as the exclamation “O Britons! (and your generous thirst of fame/Has fully prov’d you worthy of the name).” Though this prologue portrayed the British as heroes, their usual method of self promotion revolved around being seen as charitable, since their performances were advertised as benefiting widows and orphans. One typical prologue stated “The helpless offspring of the solder slain,/ No longer left to weep and mourn in vain,/ Became the object of our future care.” Some historians believe that the actual amount given to charity was quite small, given the expenses they accrued in putting up their performances.

The prevailing opinion both at the time and in the historical record is that the soldiers started their theaters as a means of alleviating boredom, or because they did not take the war seriously. One historian calls the project an “antidote for the tedium of military occupation.” There is certainly a lot of support for this theory, often from the mouths of the soldiers themselves. One Hessian officer expressed the matter succinctly, saying that during the occupation in Philadelphia there were enough “assemblies, concerts, comedies, clubs, and the like [to] make us forget there is any war, save that it is a capital joke.” Some of the soldiers realized that their reveling might be sending the wrong message. One soldier, Thomas Stanley, was concerned, saying “I hear a great many people blame us for acting, and think we might have found something better to do.” He was correct, since the soldiers’ extravagant behavior drew criticism both in America and back in Britain.

An unnamed British soldier wrote an article in a Philadelphia newspaper following the evacuation of Boston where he lamented that “England seems to have forgot us, and we endeavored to forget ourselves.” For some, theater may have helped with the feeling of isolation in a strange country. The New York prologues contain many passages about the war, including one that stated “Here we renounce the war’s unnatural strife/ For the domestic scenes of peaceful life;/…Where mirth and sadness separately strive/ To keep imagination’s flame alive.” In a way, “mirth and sadness separately strive” is an apt description of the soldier’s entire endeavor; happiness and sadness commingling to produce something truly ridiculous, often offensive, but sometimes kind of beautiful.

Sources

Scheer, George F. and Hugh F. Rankin. Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It. Cleveland: De Capo Press, 1957.

Judith Van Buskirk. “They Didn’t Join the Band: Disaffected Women in Revolutionary Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 58, no. 3 (1995): 317.

Seilhamer, George Overcash. History of the American Theatre: During the Revolution and After. Philadelphia: Globe Printing House, 1889.

Henderson, Mary C. The City and the Theatre: New York Playhouses from Bowling Green to Times Square. Clifton, New Jersey: James T. White and Company, 1973.

Nathans, Heather S. Early American Theatre from the Revolution to Thomas Jefferson: Into the Hands of the People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

"Untitled Article,” Pennsylvania Ledger (Philadelphia, PA), Sept. 25, 1776.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.