The Devil's in the Details: "Wild" by Emily Hughes

Sometimes, when the world of novels and heavily significant non-fiction weighs down on me too much, I like to wander over to the children’s shelves and entertain myself with a picture book. Due to the target audience of these books, they are always bright, fun, silly, and usually rely more on engaging imagery than they do on the often minimal text.

A few of my favorites have been Dragons Love Tacos (a story about exactly what you think it is about), Monkey With A Toolbelt (again, self-explanatory), and Niño Wrestles the World (where a baby wrestles and defeats his evil opponents in his fantastical daydream). I never exactly kept this interest secret, as it’s nice to have something in common with our miniature patrons and I don’t expect them to brush up on Kafka anytime soon, and because of this, I’ve been getting some recommendations from kids and parents alike. One that came highly recommended was Wild by Emily Hughes.

While the imagery is beautifully intricate and full of subtle details, it's a pretty straight-forward story that anyone can follow:

- A little girl lives in the wild with the animals.

- Humans take her home and try to domesticate her… unsuccessfully.

- The little girl grows increasingly frustrated and discontent with her living situation and runs away with the family dog and cat.

- The three of them rejoin the wild and live happily ever after.

It’s a great reminder for us not to take ourselves too seriously and give the wild animals in us a little room to breathe. And since the imagery really is beautiful and detailed, I began to look a little closer at those details… and I found whole other layers to the story that shocked me.

Nothing in the first part of the story was exactly off. Sure, the foxes she played with stored a skull and a few loose bones in their mudhole, but they are carnivorous after all, so that’s only natural. Soon, hunters (or “new animals”) find her in the forest and their expressions are anything but optimistic. Even while driving her to society, the passenger looks worried and cautious, and the driver looks utterly disturbed. In the foreground are chopped trees and looming in the background are dark, abysmal skyscrapers. On the license plate: FEB17. What does it mean?

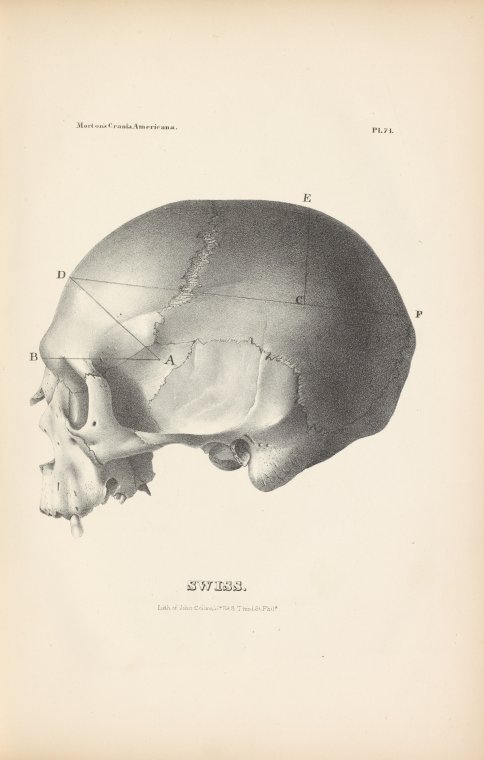

When you turn the page, the hunters are gone, now replaced with a stuffy, upper-class husband and wife. A large newspaper, dated April 18, reads “FAMED PSYCHIATRIST TAKES IN FERAL CHILD,” and it seems that he’s using some sort of apparatus to measure her head. I looked closely at the other books and posters strewn about in the psychiatrists home: Two charts of the human brain, a sculpted diagram of the human brain, three books (Masks of West Africa, The Jungle Book, and Brain Book), and a truly curious certificate: PhD of Phrenology.

Back to that license plate: February 17, 1827 happens to be the date that the Baltimore Phrenological Society was founded. If you’re not sure what Phrenology is, I’ll sum it up for you. Basically, it is a now-debunked branch of science that claimed the shape of one’s skull determined the traits of that person, and that each portion of the skull represented a particular trait: cautiousness, self-esteem, firmness, benevolence, etc. While its origins are rather unassuming, this science was debated over by abolitionists and pro-slavery activists as to whether or not people of European descent were a scientifically superior race. It was also used to determine a predisposition towards violence in young children, which quite negatively affected the upbringing of many children simply because of the shape of their heads.

Phrenology’s influence on society was not the only interesting reference in this book, however. The newspaper, mentioned earlier, is dated April 18. And that day happens to be the alleged birthdate of “Genie,” a child born in 1957 who was restrained to living in a single room until age 13. The sad details of the confined nature of her upbringing made it difficult for her to develop speech and to acclimate to the world around her. She continues to live today in a supervised home for underdeveloped adults somewhere in California.

Lastly, when we look at the timeline of the events in the book, there never was in reality such a case of a phrenologist attempting to civilize a feral child, but the closest account of a similar story comes in the form of the chilling Texas folk legend, The Lobo Girl of Devil’s River. According to legend, in May of 1835, a pregnant Mollie Dent was on the run with her husband, John, who was wanted for murder. The night she went into labor in an isolated cabin they had located, John went looking for help, and when he returned, he found Mollie dead and the infant gone. Ten years later, locals began reporting sightings of what they called a “wolf girl,” presumably the child of Mollie Dent, after being raised by wolves.

A search party managed to detain her and bring her on horseback to a ranch house where they boarded up the door and the only window. What they didn’t anticipate was that her strange howling screams would lead a pack of wolves right to them, and while the wolves took care of the guards, whose guns were no match for the number of wolves, young Ms. Dent escaped. She was seen once more at 17 watching over two wolf cubs and fled forever when she was spotted.

So be careful the next time you open a picture book as a light distraction, because there may be more story behind the story than you’ve bargained for.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.