Archives

Silas Deane: Reading and Parenting in Revolutionary America

Family history is the most personal form of history. But due to a dearth of records, in many cases it has to be written about in an impersonal way. As genealogists and family historians know well, letters and diaries are often scarce, while birth, death, census, and baptismal records are abundant. With slightly different goals in mind, historians confront the same lack of personal sources by turning to statistics, novels, and proscriptive literature in order to understand families in a given period. Yet neither strategy fully captures the personal and emotional interactions that are the foundation of family life.

As The New York Public Library has started to make available digitized collections in early American history, one question I have been asked frequently is why political elites are so well represented. Given that there are so many editions of many of their letters freely available through online databases or print at most research libraries, isn’t it just an inefficient use of resources? One of the great virtues for historians of these particularly well-documented individuals, is that a lot of their family correspondence survives, though it is not always included in edited volumes that focus on political events. And through these papers we can glimpse family life at an emotional level.

Silas Deane is a good example of what I mean. Though trained as a lawyer, Deane became a successful merchant during the 1760s. As the imperial crisis took hold, he served as a Continental Congressman. Deane is probably best remembered for a kerfuffle in Congress over allegations that he embezzled money while serving as a diplomat in France. Active as he was in revolutionary politics, he is unsurprisingly well represented in the multi-volume Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789. In the late nineteenth century, the New York Historical Society also published five volumes of Deane’s papers, which covered the years from 1774 to his death in 1789.

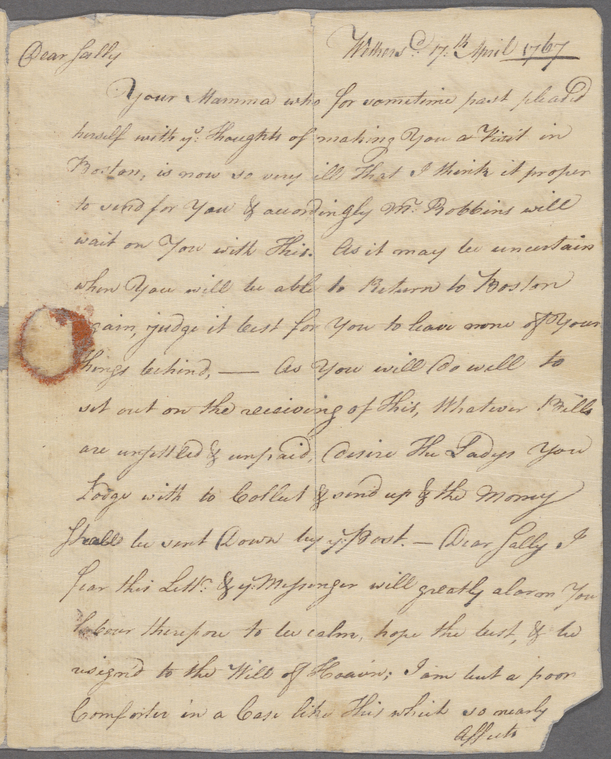

NYPL holds a small collection of Deane’s letters, which includes five letters to his stepdaughter Sarah (Sally) Webb. All from the late 1760s, none appear in the published editions of Deane’s correspondence. The letters range from devastating to heart warming to utterly quotidian. Taken together, they comprise a small archive of one father’s relationship with his stepdaughter.

In the first letter, Deane informed Sally that her mother was very ill and he was making arrangements for her to travel home to Connecticut from Boston. Understandably, he feared the letter “will greatly alarm you.” Though he could not console Sally in person, he did his best in the letter, urging her to “remember [that] your Dear Mama has been very low & Dangerous before this & God has in Mercy spared her. The same god is still able to do it” again. As he often did, Deane signed the letter “your affectionate parent & friend." Sally’s mother, Mehitable Nott Webb Deane, died later that year.

A year later, in the spring of 1768, Sally returned to Boston to finish her education. Deane was sure that Sally “will make so wise an improvement of the advantages now in your hands.” But Deane also cautioned Sally that at this “most critical, & important period of life” she would confront “a thousand byroads which lead to Ruin, & but one Path, that leads to the wish’d for stage of true Happiness.” To help her navigate this tumultuous moment, he offered ready advice, mostly about reading and writing, which he called the “two great essentials in life.”

What books Sally chose to read and how she went about reading them would bear directly on her future happiness. Deane urged his stepdaughter to “learn to pronounce the most Difficult words, with propriety.” He recommended that she “never read in haste but with moderation,” to ensure she understood what she read. This was especially true of the Bible. Ultimately, he advised her that “no Book where the Language is indecent or the subject trifling, ought to claim your present Attention” because they would do nothing to set her on the right path.

What to make of this fixation on reading habits? Deane seemed to believe that reading would influence Sally’s character and morals, as well as how she was seen in the world. Deane’s advice on reading was tantamount to advice on living a happy, worthwhile, and fulfilling life.

I don’t like the term founding fathers very much. Yet we can learn a lot when we take the term literally, when we study the founders as fathers, and as family men. Well documented as they are, founding era political elites are great fodder for historians looking to study family life in early America. No doubt Deane’s theory of parenting differed sharply from non-elites, for whom books were not as readily available, nor as intimately connected to their sense of self. The Silas Deane Letters are powerful nonetheless because they provide a fleeting glimpse on intimate family relations in the revolutionary era.

Further Reading

Lorri Glover, Founders as Fathers: The Private Lives and Politics of the American Revolutionaries (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014). Historians have used founding-era political elites in similar ways to study the nature of friendship in the period. For example, Cassandra A. Good, Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Men and Women in the Early American Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); and Richard Godbeer, The Overflowing of Friendship: Love Between Men and the Creation of the American Republic (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

On Silas Deane, see Liz Covart, “Silas Deane, Forgotten Patriot,” Journal of the American Revolution (Allthingsliberty.com), July 30, 2014, ; and Louis W. Potts, “Silas Deane,” American National Biography.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present on-line for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.