Archives

Founding Firefighters: Volunteer Firefighters and Early American Constitutional History

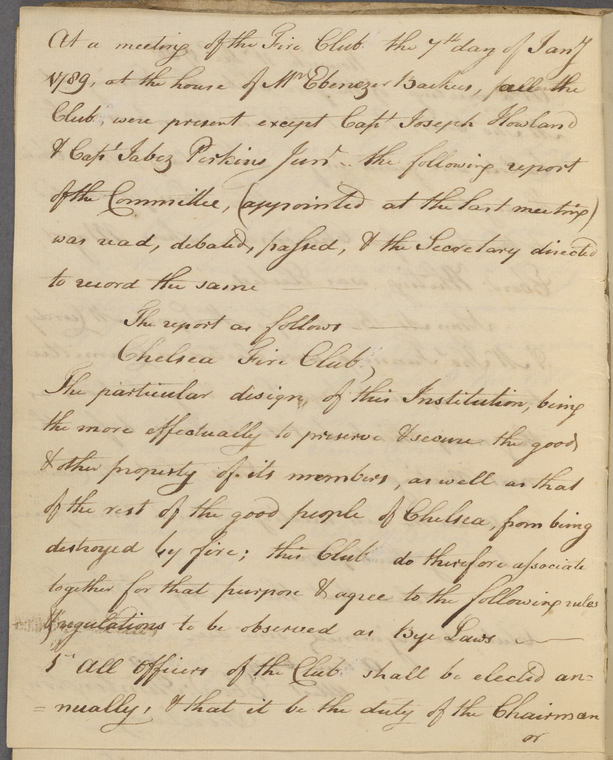

The Chelsea Fire Club formed in late 1788 to “more effectually… preserve & secure the goods & the prosperity of its members, as well as that of the rest of the good people of Chelsea, from being destroyed by fire.” This voluntary association of private men—at first no more than twenty—would be all that stood between their community and the threat of fire. Yet the records of the Fire Club reveal far more about how early Americans grappled with the challenge of self-government than about firefighting. During the United States Constitution’s 226-year history, Congress has proposed thirty-three amendments to the document and Americans have ratified twenty-seven. From its founding in 1788 to its dissolution in 1796, the Chelsea Fire Club of Norwich, Connecticut made at least eight amendments to its Constitution and “Bye Laws” in as many years. At some level, the record book of the Chelsea Fire Club merely chronicles the mundane machinations of twenty or so well-meaning volunteer firefighters in Norwich, Connecticut during an eight-year period. But in the aggregate, records like this help explain how men labored to make self-government work in early America.

The members’ first order of business after founding the Fire Club was to create a set of rules to govern it. These “Bye Laws” dealt with the same sorts of issues—election procedures, term limits, and requirements for passing new rules—that occupied the attention of the US Constitution’s framers. The bylaws mandated that the club hold annual elections for officers. Those elections, and votes on most policies including “taxes” on the membership, would be decided by a majority of written ballots. The admission of new members and the expulsion of existing members, though, required a two-thirds super majority. Votes on revisions to the bylaws and adjournments of meetings would be decided by a show of hands.

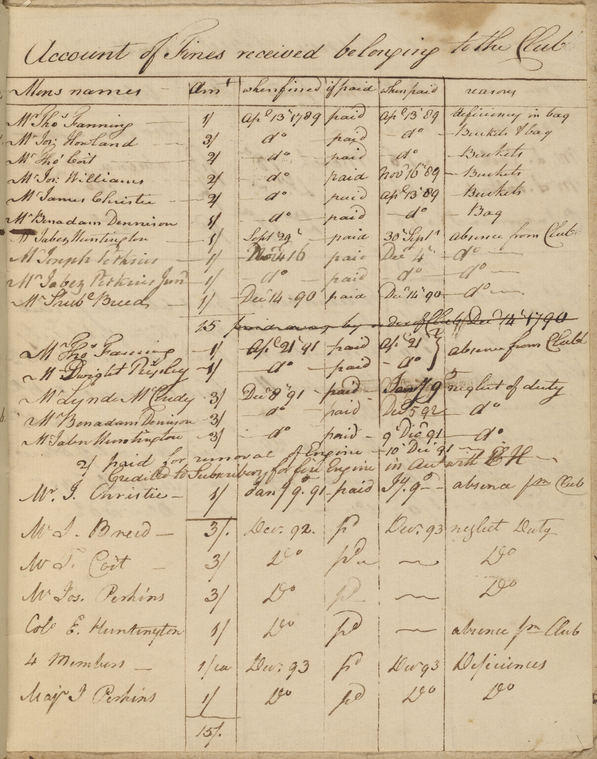

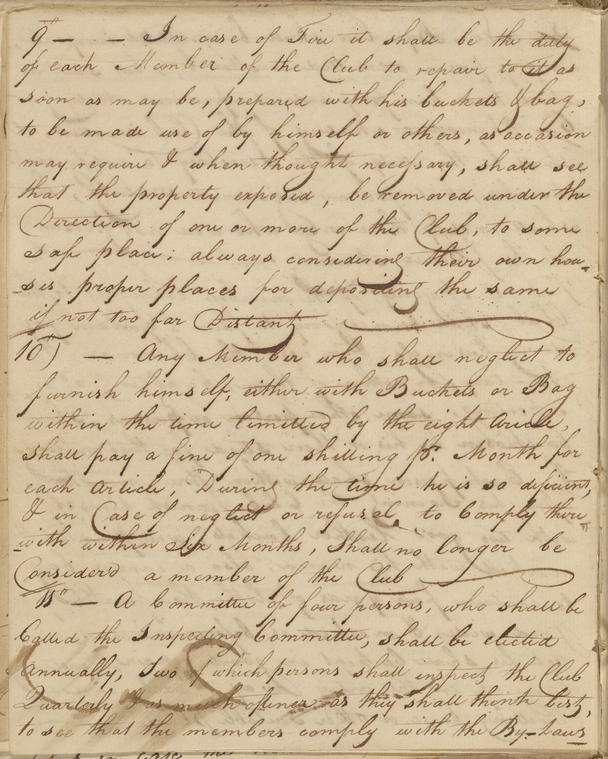

Only two articles of the initial constitution related directly to firefighting. All members had to acquire two “good Leather fire Buckets” and a canvas bag. And they had to keep those in the doorway to their homes, or another convenient place, so they could access them in the event of a fire. The club levied fines on any members who failed to get adequate supplies. Those fines paid for ladders, fire hooks, speaking trumpets, and later for the maintenance of a fire engine.

Within a few years, it had become apparent that the original bylaws were insufficient. During the first meeting of 1792, a member made a motion “to amend the first article of the Constitution” to increase the Club’s membership limit to thirty. In the last meeting of that year, another member proposed an amendment to fix a loophole created by the prior amendment, clarifying that all new members would be subject to the same penalties as the original members if they didn’t provide the required supplies.

Given all the confusion, the Club just entirely rewrote their bylaws in early 1793. The original rules had ten articles. This new version had eighteen. Among other things, the new articles pertained to the “inspecting committee,” which was charged with checking members’ supplies and levying fines.

On November 26, 1793, a fire tore through Norwich and destroyed fifteen buildings. That fire also laid bare still more deficiencies in the bylaws. A number of the members’ bags and fire buckets were destroyed during the course of fighting the blaze. There was no rule about replacing destroyed supplies. The following year saw members propose amendments to set fines for failing to replace damaged supplies, as well as revisions to the articles regulating the “inspecting committee.”

Ultimately, the Chelsea Fire Club ran out of time to perfect their constitution. By late 1795, they began to plan their own dissolution as the Club’s “necessity to exist was supposed to be superseded” shortly by a fire company created by the Common Council, Norwich’s municipal government. At their last meeting, in May of 1796, the Club resolved to turn over the fire engine and other supplies to the new fire company.

The challenges of self-government that bedeviled the Chelsea Fire Club were, in microcosm, the same challenges faced by the United States in this period. Though Americans have ratified amendments to the U.S. Constitution relatively infrequently over its entire history, eleven of the twenty-seven total amendments—including the Bill of Rights—were adopted during the Fire Club’s eight-year tenure. And the Chelsea Fire Club’s experience was hardly unique. In addition to volunteer fire clubs, Americans banded together to create debating societies, political associations, human societies, schools, and libraries, most of which were also governed by similar constitutions or bylaws. Manuscript records of these kinds of organizations are strewn through NYPL’s collection and those of many other research libraries and historical societies.

The story of early American constitutional history did not only play out at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, or even just at the state conventions to ratify the U.S. Constitution and state constitutional conventions. Americans created literally hundreds of constitutions and approved thousands of amendments while participating in voluntary associations to benefit their communities during the early years of the republic. Sources like the Fire Club’s record book are thus integral for understanding early American constitutionalism and for telling a more complete story of the American founding.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present on-line for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.