Love and Ambition: Advice from the Latin Poets

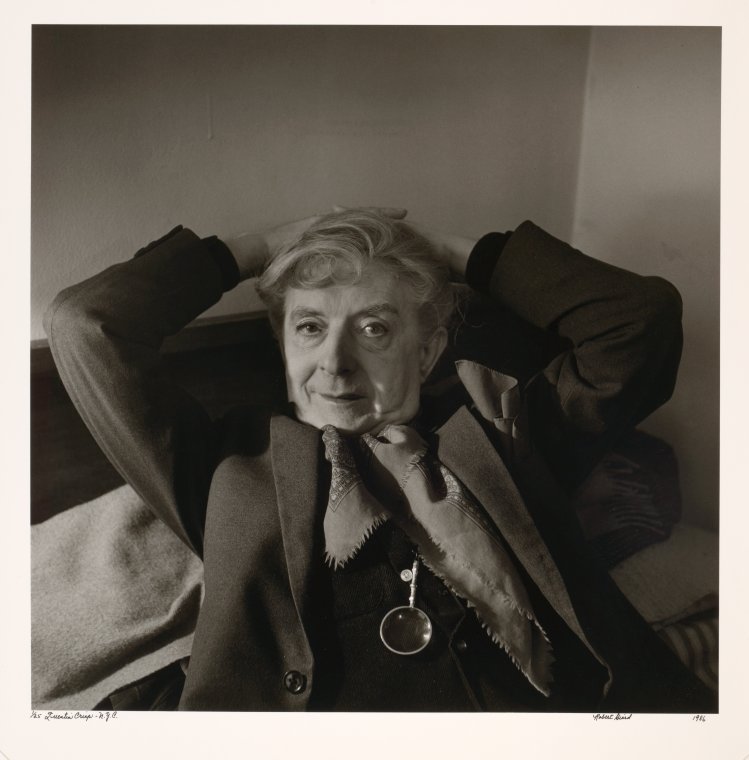

Some say that there's nothing like being single in New York City—certainly, like no other place, New York offers a slew of ways to take some time to focus on yourself, to do all of those things which a relationship held you back from, to fulfill your ambitions to your heart's content... and this is extremely valuable. Nevertheless, after spending too much time wrapped up in your own routines, you may find that things may reach the point where you can't even imagine a life which properly accommodates for another. And especially for those who actually want love, Love, with a capital 'L' becomes something altogether unreal, existing in the realm of fantasy—you may find yourself running the risk of becoming the 'incorrigible fantasist' ala Quentin Crisp, who in his memoir The Naked Civil Servant describes himself, quite shudderingly—

"[as] an incorrigible fantasist, auto-eroticism soon ceases to be what it is for most people—an admitted substitute for sexual intercourse. It is sexual intercourse that becomes a substitute—and a bad one—for masturbation."

In general, love can be tough for even the most willing if you're not at least going to let others in to your life, to part with yourself, if only just a bit. In a certain sense, love requires that you forget oneself temporarily to eventually realize yourself through someone. After all, one who is all ambition, all take and no give, will find it difficult to love someone meaningfully.

On the subject of love and ambition I am reminded always of the Latin poets (of course!) Who would not shed a tear at the parting of Aeneas from Dido as he is spurred on by the gods to found Rome? Aeneas, with those famous lines, insists that it is not by his own choice, but by the will of the gods that he seek Italy...

"Desine meque tuis incendere teque querelis:

Italiam non sponte sequor."

...which seem to neatly sum up the triumph of ambition (or duty) over love. Yet, despite Vergil's vivid portrait of Dido in wild torment over the loss of love, it's Catullus's portrayal of Ariadne in Poem LXIV which is for me the most heartbreaking, yet soberingly didactic in the lesson it teaches lovers...

Theseus's conquering of the Minotaur in Daedelus's famous Labyrinth is one of the most well known episodes in the Classical tradition. And we must not forget, his success was due to Ariadne's giving him a ball of string to mark his path so that he would not become lost in Daedelus's maze, where the Minotaur resided. After the slaying of the Minotaur, Theseus takes Ariande away with him, allegedly to start a future with her, to start a domus, a household. Then, in a moment of perfidiousness akin to Aeneas's (though much worse, I think), Theseus abandons Ariadne in her sleep on the island of Naxos. Catullus's poetical rendition of Ariadne's lament in Poem LXIV as she is witness to Theseus's departing ship is a true tear-jerker, especially since she gave up her home, her family, everything, for the sweet love of Theseus.

"[...] ut linquens genitoris filia vultum,

ut consanguineae complexum, ut denique matris,

quae misera in gnata deperdita lamentatast,

omnibus his Thesei dulcem praeoptarit amorem,

[...]"

Catullus writes this poem as someone well-versed in being scorned by another. His celebrated love of Lesbia, to whom much of his poetry is dedicated, eventually turned sour. Marion L. Daniels in her essay "Personal Revelation in Catullus 64" makes the convincing case that his depiction of Ariadne's abandonment was an attempt on Catullus's part to exercise grief over Lesbia's abandonment of himself. The poem opens with the marriage of Peleus and Thetus, the parents of Achillies (oh, when the deities would not scorn to marry mortals!)

Much like the narrative which unfolds with the shield of Achilles in Homer's Illiad, a pictoral embroidery given to the couple at their wedding leads the reader on a journey which narrates the tale of Theseus and Ariadne. In the juxtoposition of Peleus and Thetis with Theseus and Ariadne, we are given a long lasting love built out of peitas and a focus on the domus contrasted with love of fleeting passion. All the motions of love are acted out, but Theseus's personal ambition eventually proves stronger than his love for Ariadne. In stark contrast, our immortal Thetis deigned to marry a mere mortal, Peleus. How sweet.

What I love about Catullus's poem is the rough justice Theseus receives for his lack of consideration towards poor Ariadne. Ariande's ill wishes are eventually fulfilled in the suicide of Theseus's father, Aegeus, which occurs as a result of the same forgetfulness Theseus exercised by neglecting the care owed to Ariadne. Theseus was meant to display white sails to indicate victory to his father upon homecoming—in a moment of forgetfulness, he neglected to change the sails from black to white, you see... So, it was his same lack of consideration and forgetfulness which Theseus paid Ariadne, which in turn ends up in the death of his own father—Aegeus in a powerful symbolic gesture, lunges from the seat of his familial domus—and thusly, Theseus suffers deeply from his own unfailing inconsideration...

"sic funesta domus ingressus tecta paterna

morte ferox Theseus, qualem Minoidi luctum

obtulerat mente immemori, talem ipse recepit."

What can be difficult above love is that it often requires giving away a little of your ambition for the sake of your relationship with another. Yes! To scorn the high seas, to not accept that bigger paycheck, to not move across the country for that spiffy job, to realize what you have with someone may be truly worth giving a little of yourself away...

I have a soft spot for Tibullus—he leaves ambition and its ravishes to other people, those who in their constant striving for self aggrandizement are led to abuse others. In his Poem X 'Against War', the poet says that the one who first went to war was of iron himself...

"Quis fuit horrendos primus qui protulit enses?

quam ferus et vere ferreus ille fuit!"

At the root of aggressive ambition is the greedy coveting of goods, gold, jewels, the fine fabrics of Cos... and, may I be so bold as to suggest, other lovers? Tibullus inderstands regardless ambition to be what drives one to war, among other things... like the lock on the door, and the guard dog in the yard...

"hinc clava ianua sensit

et coepit custos liminis esse canis."

...and of course, behavior like leaving ones you allegedly loved stranded at Naxos despite their getting you out of a jam. For shame! Away with those evils! To do nothing but love. He goes on to praise the productivity of peace, for that which then flourishes is nothing if not a labor of love itself. This ideal lazy love is embodied in Tibullus's lines for Delia in Poem I, which begs that others may seek a fortune by conquest, if only his love for Delia remains sound...

"Divitias alius fuluo sibi congerat auro

et teneat culti iugera multa soli,

[...]

non ego laudari curo, mea Delia : tecum

dum modo sim, quaeso segnis inersque uocer."

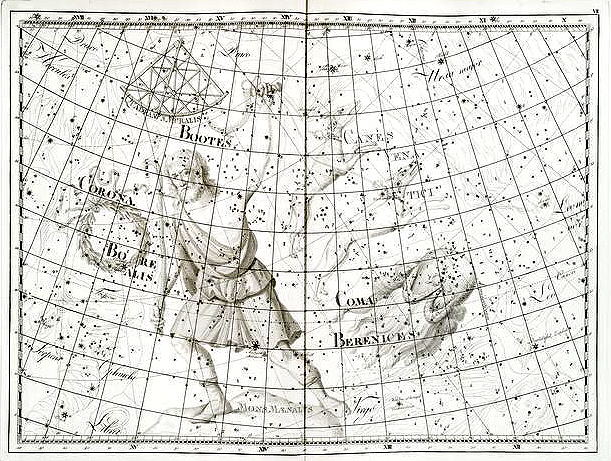

Which is why Tibullus remains, for me, the true poet for lovers... and what happened to Ariadne at Naxos? Well, she ends up betrothed to Bacchus, god of wine and revelry—so much more fun than Theseus! What's more, Bacchus promises Ariadne the sky... and delivers...

Works to Read From This Post

- Quentin Crisp, The Naked Civil Servant

- Catullus & Tibullus

- Vergil, The Aeneid

- Ovid, The Metamorphoses

- Marion L. Daniels's essay is available through JSTOR, offered onsite at library locations through nypl.org

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.