Paperless Research

Now Screening: New Electronic Resources, July 2015

NYPL recently acquired three new databases from vendor Gale Cengage: National Geographic Virtual Library, Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, and Indigenous Peoples: North America. You can use these resources on a library computer or wifi network, or anywhere else in the world with your library card number and PIN.

A quick overview of the first two databases, before we look at Indigenous Peoples more closely: National Geographic Virtual Library offers full-color issues of National Geographic Magazine; National Geographic Kids; and National Geographic: People, Animals, and the World, from 1888 to the present. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers includes over 500 publications from across the United States, providing digital access to documents that are often extremely rare and fragile in print form and supplementing other 19th century databases at NYPL, such as Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO), 19th Century British Newspapers, and 19th Century UK Periodicals.

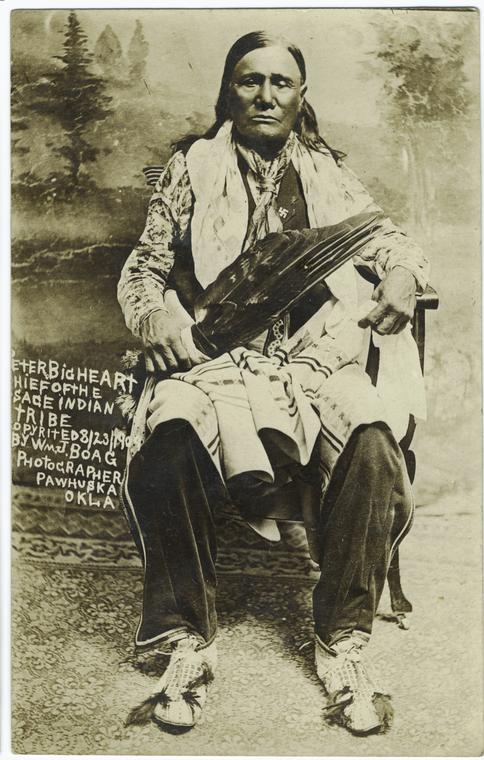

Indigenous Peoples is also a collection of digitized primary sources; or rather, it is a collection of collections—over 50, from institutions like the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and Princeton University. Documenting the history of North America’s Native American population (primarily in the United States), these collections include manuscript material related to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, newspaper articles from The Micmac News and The Indian’s Friend, and selected documents from the archives of important organizations like the Association of American Indian Affairs, the Society of American Indians, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. NYPL cardholders can access all of these special collections with the click of their mouse.

One of the collections in Indigenous Peoples is the FBI Library’s file on the Osage murders. From 1921-1923, over two dozen residents of the Osage reservation in Oklahoma were killed by an unknown assailant. In response, the community requested the assistance of the young FBI, called the BOI (Bureau of Investigation) at the time and still one year shy of J. Edgar Hoover in the director’s seat. The motive for this brutal spree was a vast oil supply discovered on reservation lands in the late 19th century. Each Osage resident received a “headright,” or portion of the oil profits, which made them both exceedingly wealthy and targets for unscrupulous and violent con men. The FBI’s investigation revealed that white settler William K. Hale, who moved to the area during the Oklahoma Land Rush, concocted a plan to inherit these headrights: his nephew, Ernest Burkhart, married an Osage woman, Mollie Kyle. Hale then orchestrated the murder of Kyle’s extended family.

By the time the FBI unraveled these details, Burkhart’s family was set to inherit over $2 million in headright funds; his wife was also being slowly poisoned. Burkhart was arrested in early 1926 and confessed his role in the scheme. Hale and Burkhart were both convicted of murder, but justice was hardly served: of the two dozen murders for which they were responsible, Hale was convicted only for the murder of Henry Roan, and Burkhart for W.E. and Rita Smith. Both were eventually paroled, with Burkhart also receiving a gubernatorial pardon.

Through a combination of browsing and searching, you can access documentary evidence collected by the FBI and preserved in Indigenous Peoples. The files include letters, official reports, telegrams, and newspaper articles, many between head field agent T.B. White and J. Edgar Hoover (sometimes using the names One Hoover and Two White).

Searching electronic versions of archival collections can be a challenge. In Indigenous Peoples, each collection comes from a different institution, so the level of description, division of documents, and quality of scanning varies. For that reason, I find it’s best to decide how to search on a collection-by-collection basis. Indigenous Peoples seems to agree: they adjust the available filters and search boxes, depending on the collection, to fit the documents.

The FBI Library’s Osage case files are grouped into larger sections, like boxes in a physical archive. Notes, a brief item listing similar to what you might see in a finding aid, are located below the image viewer and include helpful hyperlinks. Since filters don’t work too well with such large groups of disparate documents, searching is your best bet. Be sure to select the Allow variations box, as it gives you some leeway for spelling differences or faulty image-to-text transcription. The search tool also looks in the Notes and metadata for results. However, be wary when your documents have intricate handwriting, or when the quality of the scan is poor. (Many of these collections were digitized from microfilm, and their legibility sometimes suffers as a result.) These pages may not be fully searchable.

If you want to search through more databases than just Indigenous Peoples, select Extend Your Search at the top of your screen to open Artemis Primary Sources (or get there directly from the Artemis link on NYPL’s Articles and Databases page). Artemis searches across 16 different Gale Cengage primary source databases — or, you can pick and choose which databases to include with Advanced Search. It’s especially helpful if you’re interested in historical periodicals, as most of the Artemis databases specialize in digitized newspapers, magazines, and news pamphlets.

So, don't be shy — rip off the bow and wrapping paper, and start finding the treasures held within these brand new e-resources.

Can't get enough e-resources? Explore all of our databases, or our master list of available electronic newspapers, journals, magazines, and other periodicals. And if you experience any problems with one of our databases, please let us know.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.