Sea Blazers and Early Scriveners: The First Guidebooks to New York City

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Archetypes

- Giovanni da Verrazzano

- Henry Hudson

- Adriaen van der Donck

- Daniel Denton

- Last Notes

- Bibliographic Guide

Introduction

The first guidebooks to New York City were written by the navigators, explorers, and crewmen who sailed west from Europe across the Atlantic Ocean in the 16th and 17th centuries. These written works were often not intended for publication and took various literary forms, such as the famous 1524 letter by Giovanni Verrazzano to the King of France, describing the coasts of the New World, or the log jotted by Robert Juet, a ship’s mate on the Half Moon under Master Henry Hudson. Published works were called “descriptions,” “true relations,” or “peregrinations.” These written works, no matter where nor when, share the essential characteristics of a guidebook, which, for new visitors to a subject place, is to describe, recommend, and promote.

In the English language, the first published account of the harbor flowing between the islands of New York and New Jersey, written with the express purpose of addressing the public, is A Brief Description of New York, formerly called New Netherlands (1670), by Daniel Denton. Denton was preceded by a handful of “relations,” or descriptions, of the New York Bay region by Dutch authors whom often never visited the lands about which they wrote. These travelogues and descriptions are well anthologized in Narratives of New Netherland, 1609-1664, edited by J. Franklin Jameson in 1909 for the tercentennial of Henry Hudson surf-cleaving the river west of the Mannados.

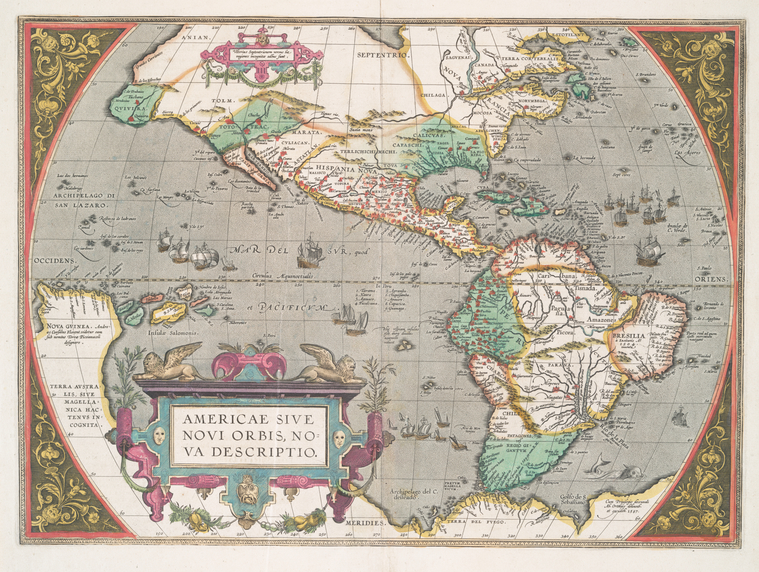

Western Europe, trudging out of the Middle Ages, was a geopolitical pressure cooker of warring, spying, and freebooting, in addition to exploring, inventing and freethinking. Giovanni Battista Ramusio, a Venetian annalist of exploration narratives, including the writings of Marco Polo, published the Verrazzano letter in 1556. In England, the reading public of the late 16th and early 17th century learned of the expanding known world in the accounts anthologized by Richard Hakluyt, a geographer described in the Encyclopedia of the Renaissance as a “propagandist for overseas enterprise,” championing the forward guard of English exploration and trade. Hakluyt was the first to publish an English translation of the Verrazzano letter. Samuel Purchas, a successor of Hakylut, published in 1625 the five book series Purchas His Pilgrimes, notably containing accounts of the four voyages of Henry Hudson.

Emanuel Van Meteren was Dutch consul in London and a cousin of famed atlasmaker Abraham Ortelius. Van Meteren met with Henry Hudson in London after the third voyage, and includes first person anecdotal information about the Skipper in his later edition of History of the Netherlanders.

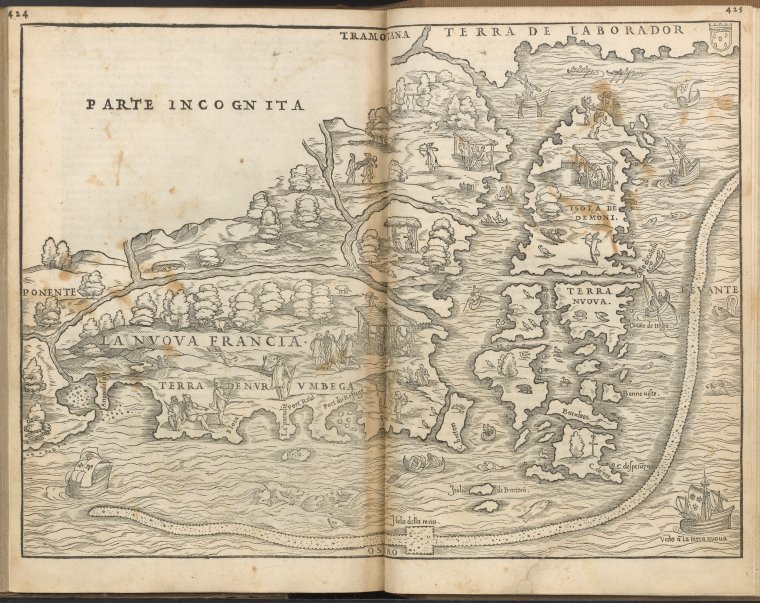

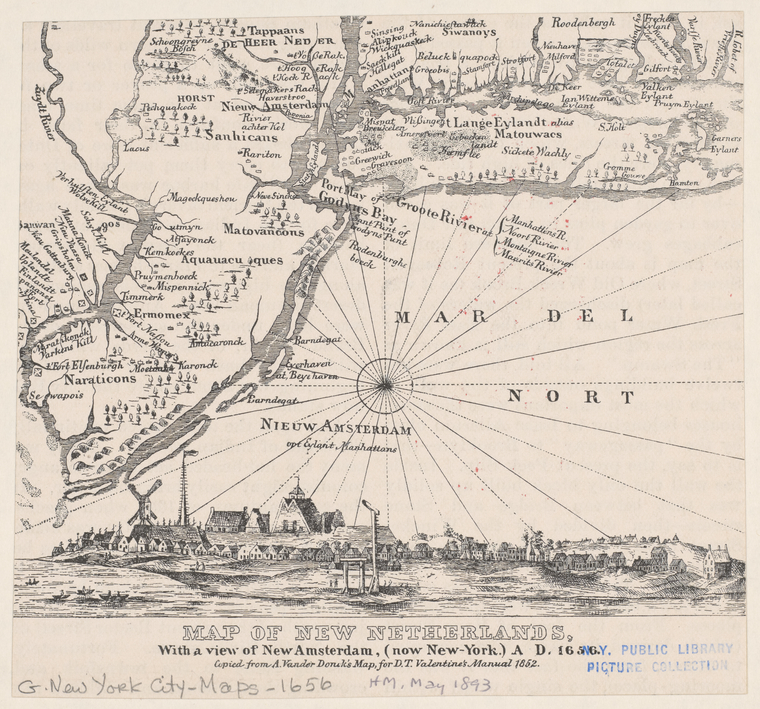

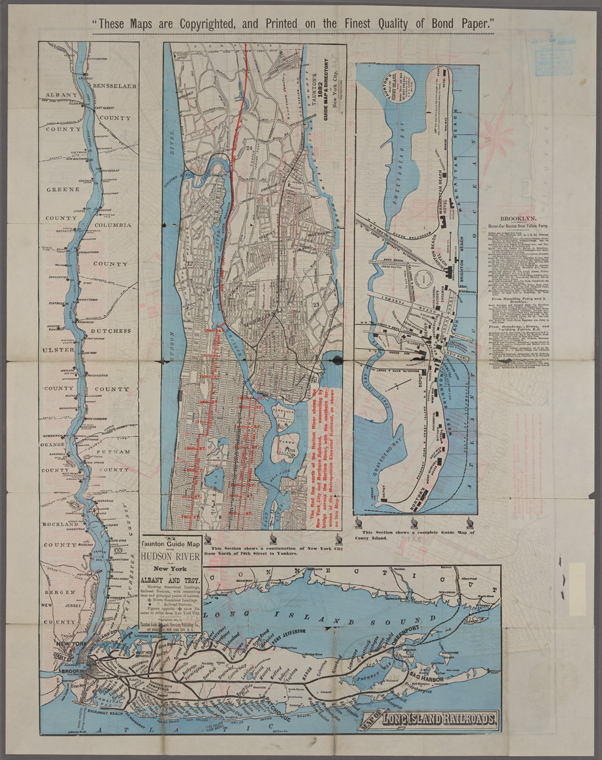

The first maps of the New York region show much Dutch nomenclature that did not stick, like the Mauritius River, Wilhelmus River, and Godenis Bay. The accuracy of maps evolved as cartographers sailed west themselves or corresponded with world explorers to gain scientific measurements about the new lands.

The skilled cosmography of Verrazzano and nautical acumen of Robert Juet are reflected in each seaman’s written works, which recordings were for the benefit of captains and cartographers. Amsterdam was home to one of the more famous mapmakers of the early 17th century, Peter Plancius, a Calvinist scrutinizer-of-globes with whom Hudson caucused personally in Latin before his 1609 voyage. Hudson is also said to have consorted with Jodocus Hondius, an engraver whose atlases were known for evocative calligraphy.

The traveler who uses a guidebook without maps will spend most of the trip lost.

Archetypes

The Rare Book Division at NYPL holds a scarce copy of what is understood as the first travel narrative published in Western Europe. The Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam by Bernhard von Breydenbach describes a journey east to the Holy Land. The volume, composed in Latin and later translated into French, was printed in 1486 and features vivid color woodblock illustrations of Venice and Jerusalem that detail costumes, commercial activity, architecture, and xenolinguistics.

Christian folklore depicts sixth century monk St. Brendan, Abbot of Clonfert, as having journeyed to unsettled western lands from Ireland on the back of a flippered sea giant.

“Brendan loved perpetual mortification,

According to his synod and his flock;

Seven years he spent on the great whale’s back;

It was a distressing mode of mortification.”

The literate public in Western Europe could read about the exploits of world peregrinators in the anthology volumes compiled and edited by Hakluyt, and Purchas. In 1596, The Voyage of John Huygen van Linschoten to the East Indies was an adventuresome two volumes that described customs, geography, sailing-routes, and “wares, marchandises, trades, waightes, myntes, and prices” of India, Indonesia, and the Far East. The Voyage was a best seller, translated to English in 1598, and likely a major provocation to organize for the future merchants of the Dutch East India Company.

Cosmographer

History has accepted that the first written account of the New York Harbor region, in any language, is the letter from Giovanni “Janus” di Pier Andrea di Bernardo da Verrazzano to King Francis I, datemarked July 8, 1524. Writing in Italian from Dieppe, France, just north of Le Havre, which port would evolve as a major embarkation point for passenger vessels carrying immigrants to New York in the late 19th century, Verrazzano reports a voyage along the coast of Florida north to Newfoundland, the “land which the Lusitanians found long ago.” Multiple copies of the original draft were transcribed and at some point translated into French legible for the King, whom was traveling in the south of France that summer. It is not known when the King received the correspondence, and the original has not survived. The most reliable extant transcription was discovered in Rome and determined to be a copy dispatched to financial backers of the expedition in Lyons and Rome.

The letter by Verrazzano “is the earliest description known to exist of the shores of the United States.” The Master and crew of the Dauphine encountered "a new land which had never been seen before by any man, either Ancient or modern." Scholars have noted the literary and nautical sophistication of the Captain’s paragraphs.

Indigenous inhabitants set "huge fires" along the seashore, signaling to Verrazzano and crew that the land was populated. Sailing north along the coast and stopping briefly along the way at the Delmarva Peninsula, the men ventured inland and found an old woman and a young woman, each with a group of children, deduced by some scholars to be Nanticoke. They gave the old woman food but leisurely took "the boy from the old woman to carry back to France." Verrazzano says that they also intended to "take the young woman, who was very beautiful and tall, but it was impossible... because of the loud cries she uttered.” Violent encounters are expressed as blankly as if measuring fathoms or describing plant life. The woman contested the genteel kidnapping until the men abandoned her to the woods, and “took only the boy."

The description of what is understood to be New York Harbor is one paragraph. "I will now tell Your Majesty about it, and describe the situation and nature of this land.” With “about 30 small boats” and “innumerable people aboard," the locale is "densely populated," an observation that would likewise apply almost five hundred years later. The land itself, an eternal, prime, vital source in both the history and future of NYC, is noted less for its real estate promise than the "signs of minerals" which Verrazzano surmises were "not without some properties of value." The Delaware tribes who greeted the sailors were "dressed in birds' feathers of various color and they came toward us joyfully, uttering loud cries of wonderment..." Just like Halston’s table at Studio…

"I shall now tell Your Majesty briefly what we were able to learn of their life and customs..." Verrazzano describes the sartorial patterns, the “rich lynx skins,” hair braidings, and jewelry made of red stones and blue crystals and copper sheets. While the Delawares emphasize pageantry and self-adornment, they are not vain. When the crew offered mirrors to trade, the Indians “would look at them quickly, and then refuse them, laughing.” And though these possessions might be traded and treasured, the Indians “are very generous and gave away all they have.” The Western Europeans perceive the lack of narcissism and the absence of selfishness in the Delawares as savagery.

Verrazzano highlights physical details of the men and women, noting facial geometries, height, and skin color. The sea captain, as with his successor navigators, presumes “they have neither religion nor laws” and “do not know of a First Cause or Author… nor any kind of idolatry.” The crew sees no houses of worship and do not interpret any behavior as an act of prayer. Still, Verrazzano admits that these assumptions result from his inability to understand the indigenous languages. Some of the tribesmen stave any engagement with the Europeans, and signal from the shores that the ship not anchor but continue moving. In a footnote, Verrazzano relates to the king how these men treated the newcomers mockingly by dropping their garments to moon the ship.

The letter ends with a highly technical “cosmographical index,” where longitudinal and latitudinal detail, spherical mathematics, “the motion of the sun,” and rising tides support a study of the measurement of the earth. In his letter, Verrazzano nods to the radical shift occurring in the perception of the “opinion of all the ancients, who certainly believed that our Western Ocean was joined to the Eastern Ocean of India without any land in between. Aristotle supports this theory by arguments of various analogies, but this opinion is quite contrary to that of the moderns, and has been proven false by experience.” The cosmographer is aware of the intrepid intellectual revolution ignited by seafaring world exploration.

"He was the first to explore the gap between the Spanish ventures to the south and the English enterprises to the north,” says one historian, and “the first commander to bring back anything resembling a detailed account of the natives of North America.” He christened the regions of New York bay Nouvelle-Angouleme, after the French city and seat of counts in the patrilineage of King Francis I. The bay was named for the King’s sister, Margarita, “who surpasses all matrons in modesty and intellect.”

Before the 1524 voyage, Verrazzano is said to have prospered as a “corsair,” or pirate, for French interests. The account of his last voyage, in 1528, was recorded by historian Paolo Giovio, whom heard it firsthand from Verrazzano’s brother, Gerolamo, and which was later augmented in verse form by Giovio’s nephew. In the West Indies, with six crewmen, the Florentine “disembarked on a deserted island…

… which seemed covered with tall trees.. The men were “taken by cruel people who suddenly attacked them. They were killed, laid on the ground, cut into pieces and eaten down to the smallest bones by those people. And there also was Verrazzano’s brother who saw the ground red with his brother’s blood, but could give no help, being aboard the ship… such a sad death had the seeker of new lands.” (Wroth, p.259)

Tough Captain

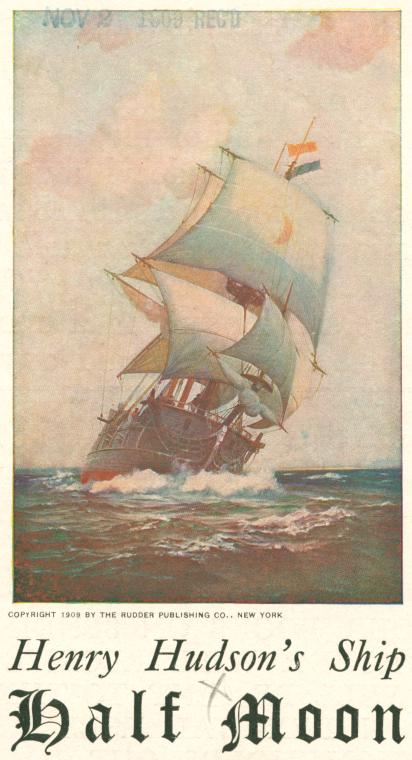

Henry Hudson embarked on four voyages to find a north Atlantic passage to Asia, sailing north, northeast, west at forty-two degrees, and finally northwest, where the English captain perished.

“They were… the first Europeans to document entry into the Delaware Bay, and to explore what came to be called New Netherland and the Hudson River… In spots Juet speaks directly to future explorers with navigational tips… and even suggests a good location to site a city…”

In 1610, as part of a new edition of the History of the Netherlanders, a multivolume work first published in 1605, Emanuel van Meteren, the Dutch consul in England, first published an account of Henry Hudson’s voyage to the New World. In addition to Meteren’s personal encounters with Hudson, the chapter was based on the 1609 journal by Half Moon captain’s mate Robert Juet. An “elderly man, cynical, skeptical, and dangerous,” the Englishman Juet would have “a sinister influence on Hudson’s fortunes.” Juet’s journal has become the canonical work in reference to the famed voyage, Hudson’s third of four in search of an alternate, northerly route to Asia. Van Meteren’s publication is an early 17th century example of a primary sourcework related to the subject of description and travel employed for historical efficacy.

Meteren’s narrative is not commercial in intent; he is a chronicler, and in the few paragraphs devoted to the Half Moon voyage to what Americans would later call New York Bay, the reader learns that Hudson led a nasty crew whom were seasoned by tropical weather, unfit for artic climates, cruel to the Indians, and intolerant of their obdurate Captain. Comprised of Dutch and English ethnicities, each band of swabbies often expressed with prejudice vulgar metaphors relating to primate species against one another.

On his first and second voyages, Hudson sailed as an agent of the Muscovy Company, based in London, which conducted trade with Russia and was founded upon a geopolitical friendship between Queen Elizabeth and Ivan the Terrible. Hudson believed he might sail directly through the North Pole, which he and Calvinist cartographer Peter Plancius anticipated as a region of melting ice and warmer climates as a result of the six months’ midnight sun between the vernal and fall equinoxes. Hudson failed in proving this theory, and on the next trip sailed north to Nova Zembla. The ship’s log which Hudson wrote on this excursion has been published. The crew slaughtered walruses, claimed to have seen a mermaid, and, increasingly hungry and cold, pressured the skipper to turn back when the ship reached the Lofoten Islands.

Returning a second time with little fanfare, Hudson lost favor with the Muscovy Company, but was soon invited to the Netherlands by the directors of the Dutch East India Company, “the seventeen gentlemen.” The Company held a trade monopoly on the long and perilous southern routes to Asian markets, and eagerly sought to advance any potential routes north. In addition, the United Netherlands—the territories which severed allegiance from Spain in 1576, causing ongoing regional conflict—were brokering an armistice with Spain. The Dutch were apprehensive that the agreement would demand that Spain share trade routes to Asia. When van Meteren, who liaisoned with Hudson in London, arranged for the explorer to visit the growing cosmopolis of Amsterdam, the “seventeen gentlemen” were not all in agreement that Hudson was the right choice. Some were suspect of the communications Hudson had recently received from Pierre Jeannin, Minister to Henry IV of France, in collusion with a formerly ostracized director of the Dutch East India Company; but it was a short-lived courtship. Though England and the Netherlands were enemies in world trade, and a British explorer sailing for the Dutch in the 1600s was akin to a Russian astronaut during the Cold War flying to the moon in an American rocketship, the two nations shared the greater enemy of Spain, which superpower each nation might beat to the rich trade in the “land of spicery” if a northwest route was trailblazed.

The voyage began north, with no intention of a westernly direction. The Half Moon later turned south from the unnavigable ice waters Hudson believed would have taken him and his crew to India. At “Nova Francie” the crew seized provisions from the indigenous people “by force,” and Hudson directed the ship westward.

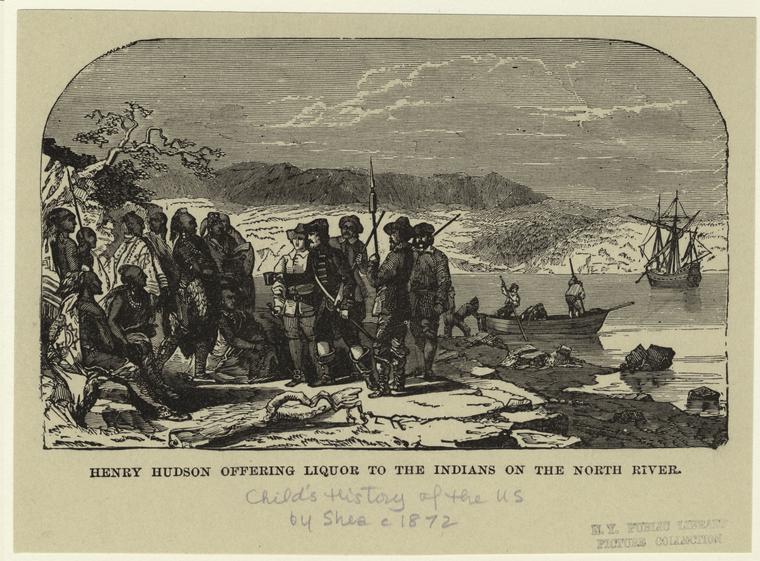

The Juet journal “called the attention of the Dutch to the desirableness of the North River region and its value for the fur-trade.” Like Verrazzano, Juet is technical, describing time and space in fathoms, hourglasses, degrees, leagues and soundings. The land is “high and pleasant.” From the coastal waters, the crew catches mullets a foot and a half in length and sting-rays that take four men to haul on deck. “The people of the Country” come aboard the ship and trade green tobacco and maize for knives and beads.

Crossing the mouth of the harbor, five men in canoes scouted the upper bay and paddled through the Kill van Kull, an area running between Staten Island and Bayonne which Juet describes as having “very sweet smells.” The men are then “set upon by two Canoes” carrying a total of 26 Indians. Juet details the bellicose exchange between the parties in the same bloodless monotone as sea-depth or weather conditions. “…One man was slaine in the fight, which was an English-man, named John Colman, with an arrow shot into his throat.” Juet does not say what triggered the confrontation. The next day Colman was buried at the shores of what is said to be Sandy Hook. Hudson’s crew renamed the place Colman’s Point.

Not unlike an episode of Mad Men, tobacco and alcohol abound. First contact with the indigenous tribes relied on trade in the nicotine weed, less perhaps as a commodity than as an object of goodwill in the art of giftmanship. But even when the Indians made a “shew of love,” offering up other tradestuffs like oysters and beans, Juet repeats that “we durst not trust them.” Juet tells how the crew invited several Indians to the ship to get them drunk on wine and “aqua vitae,” testing “whether they had any treacherie in them.” It was determined that they did not. Still, the crew somehow managed to capture two Indians, one of whom was later released while the other escaped by diving overboard.

Juet details a raid by one of the "people of the Mountaynes" who paddles along the ship’s stern to steal pillows, shirts and “bandaleeres” from Juet’s room through the cabin window. The raider is shot through the chest while the Half Moon cook chops off the hands of an abettor in the canoe.

Nineteen days in, the ship reached the future site of Albany. After trading knives and beads “amicably” with tribes along the upper Hudson and clashing with arrow-shooting canoemen at the lower, the skipper, sensing well the increasingly mutinous agitations of the crew, favored sailing back towards England rather than turning north to “winter in Newfoundland.” The presence of freshwater upriver proved that the waterway was not a trans-oceanic passage.

Anticipating a brief layover before continuing to Amsterdam, where his wife and children dwelled, Hudson docked at the port of Dartmouth on the southern coast of Great Britain. He traded dispatches with the East India Company and bunked for over a month on the berthed Half Moon. Hudson was then detained by English government authorities, forbidden future communication with the Netherlands, and restricted from re-embarking. The journals, maps and charts produced on his third voyage were confiscated. As a result, Stokes relates how subsequent coastal maps of the New York region made in England were much more accurately detailed, including a 1624 map that makes an early reference to the “Hudson” river. Dutch maps lacked the benefit of Hudson’s intelligence, seized like atomic secrets by enemy nations in World War II.

Hudson may have possessed maps forwarded him by cavalier John Smith of Jamestown, Virginia. On his New York voyage, it is surmised that an unknown crewmember may have drafted a map of the harbor that later circulated in London. The map is said to have been obtained furtively by a Spanish diplomat named Velasco and couriered to Spain, where it was discovered in the 1880s in Spanish government archives. On the map, variations of the term from which “Manhattan” derives its Eastern Algonquian etymology are used to identify the areas on either side of the Hudson River. Algonquian linguist Ives Stoddard proves that the correct original meaning of the term is “place for gathering the wood to make bows,” in reference to the abundance of hickory trees at the lower tip of the island. Though “Manhattan was the first Native American place-name to be recorded by Europeans between Chesapeake Bay and the coast of Maine,” the term, at least here, was also ascribed to New Jersey. Likewise, in his mate’s log, Robert Juet refers to the western bank of the river as "Manna-hatta," as if New Jersey was an antecedent in the naming of Manhattan Island. Though Juet likely was just confused, and a strong theory holds that the Velasco map is a fake, the mortification of Manhattanite identity is psychically fixed.

Johannes De Laet, a Dutch scholar and bibliognost, published a popular series of books on geography and government, the Novus Orbis, which covered the whole of the coastal Americas, from the West Indies to New France. De Laet’s 1625 edition includes passages from the alleged journal of Hudson’s third voyage penned by Henry Hudson himself, and since lost. De Laet was also a director in the Amsterdam Chamber of the Dutch West India Company, and naturally eager to promote the opportunities of the Company’s new colony. The 1625 edition predated the infamous business agreement between Peter Minuit and Lenni Lenape tribesmen, when the Dutch purchased claim to Manhattan for 60 guilders. Fifteen years earlier, Hudson had signed a contract with the Dutch West India company for 800 guilders. Hudson’s journal is quoted at length, describing ingratiating encounters with the indigenous people, which include a meal of game pigeons and a “fat dog.” Remarks upon the forests, fishlife and Indian manners are excerpted. “It is as pleasant a land as one can tread upon,” says Hudson.

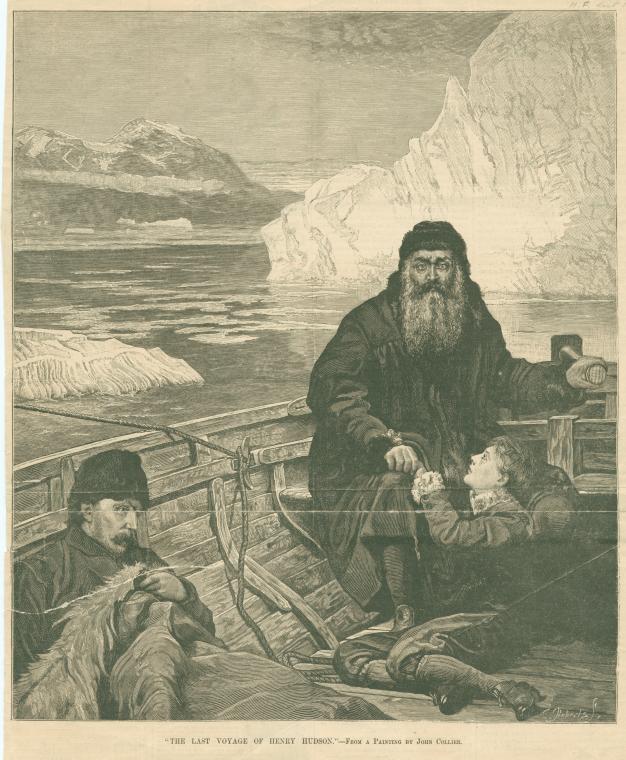

Hudson’s third voyage brimmed with mutinous intent, yet without action. When Hudson sailed under the auspices of England a final time, on the ship Discovery, the voyage barely reached the mouth of the Thames before Hudson kicked off one of the crewmembers, for unknown reasons. As ill-will brewed, Hudson unwisely chose to winter in the arctic no man’s land of Hudson Bay, where the crew survived on ptarmigan. Suspecting that Hudson was secretly stashing food for himself, his son John, and favored crew, a fractious band of mutineers formed and overtook the captain. Ransacking Hudson’s cabin, the rebels found hidden stores of beer, biscuits, pork, butter, peas and aqua-vitae. Hudson, his son, and seven sailors were forced into a shallop and shoved off upon the arctic ocean void.

The only sources for what occurred during and after the mutiny are found in exculpatory passages in the journal of Abacuck Prickett, one of the survivors of the fourth voyage; and an incomplete series of documents discovered in the London Public Records Office in the 19th century concerning the fangless proceedings against the mutineers, none of whom were punished or sentenced. Prickett’s journal presents the writer as innocent, while instigators of the mutiny are cited as the two crewmembers who died en route back to England, Henry Greene, shot by Eskimos, and journalkeeper Robert Juet, who starved to death.

Lawyer Man

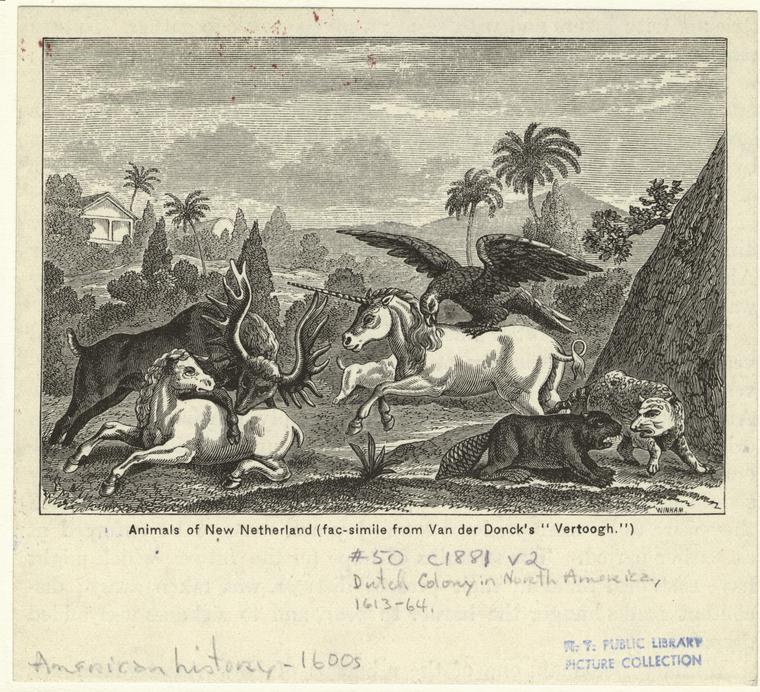

A milestone proto-guidebook to New York is A Description of New Netherland, published in 1656 and authored by Manhattan’s first attorney, Adriaen van der Donck (1620-1655). An early firsthand account of the colony and surrounding lands, the Description concludes with an invented conversation between a Dutch “Patriot” and a "New Netherlander" colonist. The Patriot asks, Is the colony prosperous to the homeland? Is it defensible against attacks and piracy? Does it offer "good opportunities for business?”

Naturally, the New Netherlander answers favorably to all three. The priorities of new world expansion are sharply reflected in the "Conversation," in order to play upon the interests of possible settlers and merchants. Before issues of rights, government or law, "trade is the object," says the New Netherlander, "and on trade we must depend." The Netherlands and Spain were battling a global trade war that would soon find Spain supplanted by Great Britain, which nation would surpass the Dutch as a world superpower; not least of its victories would be the peaceful yet forceful ejection of the Dutch from the region to which they were the first Europeans to lay claim.

In laying out the commercial advantages of the colony, the New Netherlander cites business abuses and corruption in the early decades of Dutch West India Company rule. Here, "interest," meaning personal greed, was the toxic influence upon merchants. "Informed persons know that not a quarter of the profit made on company merchandise flowed into the company's coffers, yet when loss was incurred, it was borne by the company alone.”

For biographical and intellectual context related to van der Donck and his works, see the cogent, enlightening introduction by scholarly New Netherlander Russell Shorto which opens the 2008 edition of the Description. Shorto characterizes the work as a certain prophecy, noting the visions of promise implied in the lawyer’s “raw and rough classic.” With a taxonomic zeal, van der Donck promotes the trade colony to inspire the migration of homeland Dutch. “New Netherland,” the Description opens, “is a very beautiful, pleasant, healthy, and delightful land, where all manner of men can more easily earn a good living and make their way in the world than… any other part of the globe that I know…” Four hundred years later in New York City guidebooks, it is a familiar schpiel.

A New York Tour Guide in New Jersey

“Never any Relation before was published to my knowledge,” writes author Daniel Denton in A Brief Description of New York, published in 1670, six years after the Duke of York claimed New Netherland for Great Britain, and nearly twenty-five years after van der Donck’s Description. Denton is the English language successor to van der Donck; he enjoys the beauty and prospects of the new lands and hopes people will settle them. It is tempting to exult the Description as the first true guidebook to New York City in English, if one is gripped by the conditioning of superlatives. Like van der Donck, Denton wrote with the intention of publishing for a mass audience, and facts are based on his own first person experience.

The work is densely subtitled: … with the Places thereunto Adjoyning. Together with the Manner of its Scituation, Fertility of the Soyle, Healthfulness of the Climate, and the Commodities thence produced. Also Some Directions and Advice to such as shall go thither: An Account of what Commodities they shall take with them. The Profit and Pleasure that may accrew to them thereby. Likewise a Brief Relation of the Customs of the Indians there.

The “Fertility of the Soyle” promotes the economic sustenance of the land, ripe for property; the “Healthfulness of the Climate” eases concerns about the livability of the regions; and the “Commodities thence produced” suggests that the place is good for business.

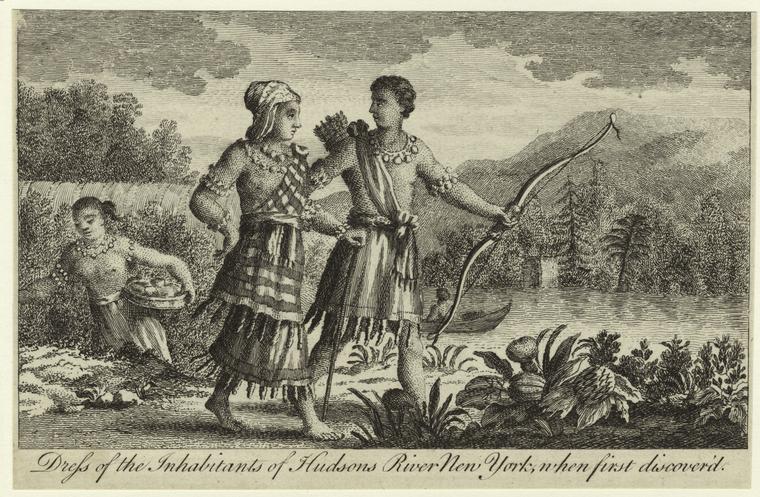

Denton’s account provides “some Directions and Advice to such as shall go thither,” in support of the “profit and pleasure that may accrew” on behalf of visitors. Though this is the familiar vernacular of guidebooks, Denton is not writing for passing visitors, but permanent settlers. Denton’s guidebook intends to set at ease the fears of potential newcomers vying for a life in the unknown frontier world. Denton casts himself as one seasoned in the ways of the region, as well as “Customs of the Indians there.” This detail might ease fears of Europeans biased by reports of Native American violence against whites, as well as invoke the virtues of exotica about the local inhabitants. Curiosity is tempted, and a certain objective, early and unformed anthropology is nodded to. Denton is generally fairminded in his depiction of Indian tribes.

The pamphlet is prefaced “To The Reader,” and the author unfolds a plainspoken but mystical creed of the traveloguist, a “brief but true relation of a known unknown part of America.” Denton asserts he only writes “but what I have been an eye witness to,” since so much hearsay is bandied about in reference to such phenomena as undiscovered riches in the “Bowels of the earth not yet opened.” Denton signs off that he “desireth to deal impartially with every one.” No European is unavailed the opportunity of a trip to the colony of New York.

In the opening paragraphs, Denton describes the geographical boundaries of the colony, “betwixt New England and Mary-land.” The author also includes a pitch for newcomers to acquire lands in New Jersey and form landowning groups, known as Associates, after receiving patent approval from the Governor. By 1670, Jersey had been divided by proprietors into East and West. Denton himself writes his New York book as a founding landholder in Elizabethtown, in East Jersey, after having decamped with other migrants from the future Queens County.

The early paragraphs also plug the military advantages of the region, noting that the “violent stream” at Hell-Gate is a “place of great defence against any enemy,” and that the “Fort at New York” is “one of the best Pieces of Defence in the North parts of America.”

Denton then proceeds to note things practical and sensual. His work confirms that guidebooks will always be viable research resources, the type that take on new life when the initial use has expired, like phonebooks or fire insurance maps. Denton details the abundant fruit, timber, marine life, and herbs native to the habitat, the mulberries and plums and huckleberries; the oak, birch, hazel, maple and cedar trees; the Sheepshead, Perch, Trout, Eels and Whales; and the “Egrimony, Violets, Penniroyal, Alicampane” which support what “the Natives do affirm, that there is no disease common to the Countrey, but may be cured without Materials from other Nations.” The York soil is arable for English grains, tobacco, flax and hemp. Such details, along with the litany of land-dwelling wildlife, paint a portrait of virgin territory, soon adulterated.

Denton depicts a forebear to the Belmont Stakes in Long Island, where because of “fine grass… once a year the best Horses in the Island are brought hither to try their swiftness, and the swiftest rewarded with a silver Cup, two being annually procured for that purpose.” This unexpected reference may possibly be the first to the practice of horseracing in New York.

Denton spends a good length describing the Indians, prefacing that “there is now but few upon the island,” and though they “are in no ways hurtful but rather serviceable to the English,” Denton demonstrates ontological pre-American supremacy which bodes somewhat apocalyptically 350 years later:

“It is to be admired, how strangely they have decreast by the Hand of God, since the English first setling of those parts… and it hath been generally observed, that where the English come to settle, a Divine Hand makes way for them, by removing or cutting off the Indians either by Wars one with the other, or by some raging mortal Disease.”

17th century Lenni Lenape tribes of the region play “Foot-ball and Cards,” and imbibe “strong drink" over drinking games. Denton casually notes that sometimes these games end in a drunken murder, which might then provoke a revenge murder “unless he purchase his life with money.” The money is made of black, white, and periwinkle shells.

Denton notes the tribes’ sartorial habits; the vital rituals of marriage and death; the peoples’ combat behaviors; the legal system of Council before the Sachem; and the biannual “Conjuration” of the priests, when invocations are made and money is offered to the gods in return for war favors or a successful corn harvest. Naming customs and language patterns are explained, in addition to medicinal practices, the relationships between the sexes, and “their Cantica’s or dancing Matches,” which are portrayed as if a 1960s Happening in a Wooster Street loft space, where, facepainted “black and red… with some streaks of white under their eyes,” they “jump and leap up and down without any order, uttering many expressions… wringing of their bodies and faces after a strange manner, sometimes jumping into the fire…”

It is also noteworthy that, divine genocide aside, Denton deliberately impresses the reader of how well the English get along with the Indians, unlike the rapacious and bloody relationship the Indians had had with the Dutch.

Denton concludes the Description by enumerating reasons that settlement is a smart decision. Skilled workers populate the region and one “need not trouble the Shambles for meat, nor Bakers and Brewers for Beer and Bread.” Matched with the elysian natural resources, “where many people in twenty years time never know what sickness is,” Denton argues that “I may say, and say truly, that if there is to be any terrestrial happiness to be had by people of all ranks, especially of an inferior rank, it must certainly be here.” In this first English guidebook to New York, one finds the god-spurred manifest destiny of the white man, the primacy of real estate, and the opportunity for “all ranks” to aspire and succeed. These seedings reflect both the beneficial and malevolent values of future Americans, who, “with God’s blessing, and their own industry, live as happily as any people in the world.”

Last Notes

The genesis of NYC guidebooks is found in these multiform 16th and 17th century literary works, which reflect the exaltation inspired in those whom have had first encounters with the New World. In the letter to the King, the mate’s journal, the intellectual’s travelogue, and the published “true relation,” one simply substitutes the sailing vessel for the red doubledecker tour bus.

Bibliographic Guide

Search the NYPL catalog by subject, using the sample subject headings suggested below. In addition, browse the catalog record of individual titles for likewise subject headings.

Subject Catalog Search

- America — Discovery and exploration — Early works to 1800.

- America — Discovery and exploration – [ETHNICITY].

- EX: America — Discovery and exploration — Dutch.

- EX: America — Discovery and exploration – French.

- New York (State) — Description and travel — Early works to 1800.

- Voyages and travels — Early works to 1800.

- Indians of North America — New York (State) — Early works to 1800.

- Long Island (N.Y.) — Description and travel — Early works to 1800.

Chroniclers, Compilers and Cartographers

This is an introductory list of noted Western European mapmakers, and publishers, writers, or anthologizers of exploration narratives in the late Medieval period through the Renaissance.

- Johannes De Laet

- Hakluyt, Richard, 1552?-1616

- Linschoten, Jan Huygen van, 1563-1611

- Ogilby, John, 1600-1676

- Ortelius, Abraham, 1527-1598

- Purchas, Samuel.

- Ramusio, Giovanni Battista, 1485-1557

- Sanson, Nicolas, 1600-1667

Early NYC Exploration & Description & Travel

- Jasper Danckaerts was a Dutchman who kept a journal on his 1679-80 voyage to New York and other colonies.

- Hoffman, Bernard G. From Cabot to Cartier: Sources for a historical ethnography of northeastern North America, 1497-1550. University of Toronto Press. 1961.

- Jameson, F. Narratives of New Netherland, 1609-1664. Full text online at HathiTrust .

- Weslager, C. A. Dutch explorers, traders, and settlers in the Delaware. 1961. Excellent source of early Dutch narratives and bibliographic records related to the New York and New Jersey region.

Verrazzano

- Codignola, Luca. “Another Look at Verrazzano’s Voyage, 1524.” Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region. University of Genoa.

- Verrazzano, Giovanni da, 1485-1528.

- Verrazzano letter to King Francis I

- Canadian Dictionary entry on Verrazzano.

- Wroth, Lawrence. The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano (1970) by Lawrence Wroth is seems the most prodigious work on the subject, with copious biographical detail and bibliographical explication, and chapters called “What Verrazzano Knew,” and “The Voyage of 1528 in Manuscripts and Printed Books of the Sixteenth Century Literature.” Published for the Pierpont Morgan Library by Yale University Press.

Henry Hudson

- Hudson, Henry, -1611.

- Chadwick, Ian. Thorough and informative website devoted to Hudson by a retired journalist, producer, and devoted Hudsonaut.

- Janvier, Thomas A. Henry Hudson, a brief statement of his aims and his achievements: to which is added a newly-discovered partial record, now first published, of the trial of the mutineers by whom he and others were abandoned to their death. 1909.

- Juet's journal. The voyage of the Half moon from 4 April to 7 November 1609, by Robert Juet. Introduction by John T. Cunningham; edited by Robert M. Lunny .

- Mak & Shorto. 1609: The forgotten history of Hudson, Amsterdam and New York. Henry Hudson 400 Foundation, 2009.

- Mancall, Peter C. Fatal Journey: the final expedition of Henry Hudson, a tale of mutiny and murder in the arctic. NY: Basic Books, 2010.

- Murphy, Henry C. Henry Hudson in Holland. 1859.

- Powys, Llewelyn. Henry Hudson. NY: Harper & Bros. 1928.

- Pritchard, Evan T. Henry Hudson and the Algonquins of New York: native American prophecy & European discovery, 1609. SF: Council Oak Books, 2009.

- Purchas, Samuel. Purchas His Pilgrimes, Vol III includes Hudson’s four voyages, the Juet journal, Hudson’s journal excerpt, and the journal of Abacuck Prickett, mutineer.

- As with most New York historiography, see the Index of Stokes’ Iconography under “Explorers.”

Daniel Denton

- Denton, Daniel

- A brief description of New York: formerly called New Netherlands / by Daniel Denton.

Adriaen van der Donck

- A Description of New Netherland (1656) 2008 ed.

- Remonstrance of New Netherland, and the occurrences there… (1649)

- Shorto, Russell The Island at the Center of the World . NY: Vintage Books. 2005.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

![[St. Brendan holding mass on the back of a whale.]](https://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=ps_rbk_cd14_210&t=w)