The Mythology of Bruno Schulz

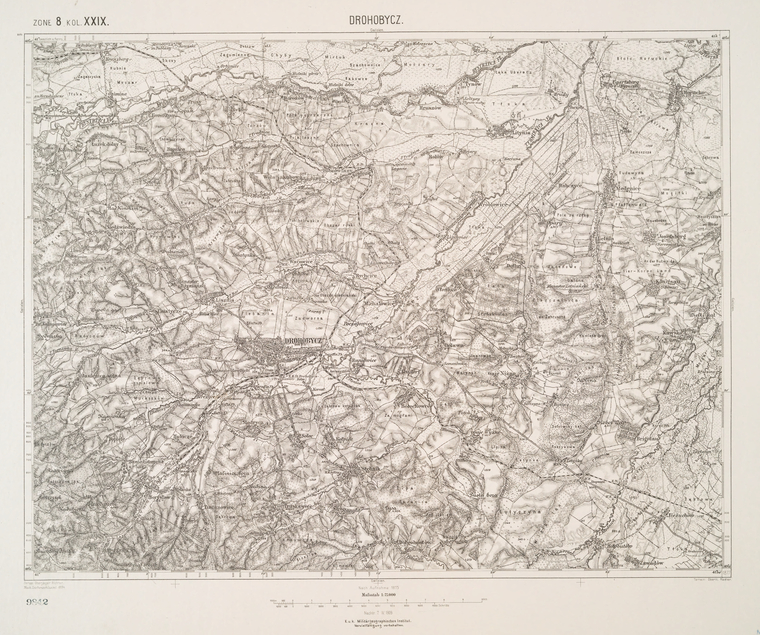

How did a Jewish writer, who wrote exclusively in Polish and who died in the Holocaust, become practically a cult figure of mid-20th century literature? From Drohobych (in transliteration from Ukrainian; the Polish form is Drohobycz): a small city, once in the province of Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian empire, until 1918; then the Second Polish Republic between the world wars; then occupied first by the Soviets in 1939-41, and subsequently by the Germans in 1941-44; after that, in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic; and now a city of independent Ukraine. This was the home town of Bruno Schulz (1892-1942), a Jewish-Polish writer whose life, death, and afterlife have become something of a literary myth. “Myth” and words derived from it, in fact, are most often applied to his work. In the standard critical biography, Jerzy Ficowski’s Regions of the Great Heresy, the linkage of Schulz and “myth” is made evident. Even a quick look through Ficowski’s work turns up, besides many uses of the basic words, “myth” and “mythology,” one finds “mythic,” “mythologizer,” “mythological,” “mythical,” “mythologically,” “mythologization,” “mythologizing.” This is not only Ficowski’s invention; the idea of “myth” is one generally accepted in connection with Schulz and his writing and art.

Schulz led a life that was provincial, but he was also, after his “discovery,” deeply involved in the literary world of Poland. He taught arts and crafts in high schools, frequently referring to his “depression” over the burden this placed on his creativity. He was an artist before he was a writer; he was “discovered” by the Polish literary world only in the mid-1930s, only a few years before the outbreak of the Second World War. During the occupation by the Germans, he was forced into the Drohobych ghetto with the rest of the city’s Jews. But he also found a “protector” of a sort, a local Gestapo head, who admired his art and made use of his skills. This did not help him on 19 November 1942, when he was killed by the Germans during a “wild (that is, unplanned) murder action,” and buried in an unmarked grave. The exact site has never been identified.

The notion of “the book” which holds all of life’s mysteries is one key to Schulz’s fiction. Here begins the first story in his second and last collection of stories, Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass:

I am simply calling it The Book without any epithets or qualifications, and in this sobriety there is a shade of helplessness, a silent capitulation before the vastness of the transcendental, for no word, no allusion, can adequately suggest the shiver of fear, the presentiment of a thing without name that exceeds all our capacity for wonder. How could an accumulation of adjectives or a richness of epithets help when one is faced with that splendiferous thing? Besides, any true reader—and this story is only addressed to him—will understand me anyway when I look him straight in the eye and try to communicate my meaning. A short sharp look or a light clasp of his hand will stir him into awareness, and he will blink in rapture at the brilliance of The Book. For, under the imaginary table that separates me from my readers, don’t we secretly clasp each other’s hands? (“The Book”).

Schulz’s legacy can be found in in the works of a number of leading Jewish writers. Cynthia Ozick’s The Messiah of Stockholm (1987) is probably the outstanding novel extending Schulz’s legacy; he doesn’t actually appear, but his purported last writing, the manuscript of “The Messiah,” does. (This manuscript has never been found and survives as a hoped-for dream among followers of Schulz. It either never existed, or was hidden but still not found, or perhaps destroyed during the Second World War.) He also appears in the Israeli novelist David Grossman’s novel, See under: Love (1986). Perhaps the most original use is Jonathan Safran Foer’s, Tree of Codes (2010). The publisher's note states: “In order to write The Tree of Codes, the author took an English language edition of Bruno Schulz's The Street of Crocodiles and cut into its pages, carving out a new story." This doesn’t make for readability, but it’s certainly an unusual treatment!

In Schultz’s Letters and Drawings,we find his views on his first book (known as Cinnamon Shops, Sklepy cynamonowe, in Poland, and The Street of Crocodiles in the United States):

To what genre does Cinnamon Shops belong? How should it be classified? I think of it as an autobiographical narrative. Not only because it is written in the first person and because certain events and experiences from the author’s childhood can be discerned in it. The work is an autobiography, or rather a spiritual genealogy, a genealogy par excellence in that it follows the spiritual family tree down to those depths where it merges into mythology, to be lost in the mutterings of mythological delirium. I have always felt that the roots of the individual spirit, traced far enough down, would be lost in some matrix of myth. This is the ultimate depth; it is impossible to reach farther down.

Writing to a potential Italian publisher for Cinnamon Shops, Schulz said: “This book represents an attempt to recreate the history of a certain family, a certain home in the provinces, not from their actual elements, events, characters, or experiences, but by seeking their mythic content, the primal meaning of that history” (also in Letters and Drawings).

It seems best to conclude with the last story in Sanatorium. The father is a mythic character, struggling with the world, and disappears at the last, in the form of a cooked crab.

But my father’s earthly wanderings were not yet at an end, and the next installment—the extension of the story beyond permissible limits—is the most painful of all. Why didn’t he give up, why didn’t he admit that he was beaten when there was every reason to do so and when even Fate could go no farther in utterly confounding him? After several weeks of immobility in the sitting room, he somehow rallied and seemed to be slowly recovering. One morning, we found the plate empty. One leg lay on the edge of the dish, in some congealed tomato sauce and aspic that bore the traces of his escape. Although boiled and shedding his legs on the way, with his remaining strength he had dragged himself somewhere to begin a homeless wandering, and we never saw him again. (“Father’s Last Escape”).

In 2014, the Library bought a first edition of Schulz’s Sanatorium, now a great rarity. In 2015, meanwhile, we acquired an edition of a work by the person who served as something of a “muse” for Schulz, encouraging his work: Dvoyra Fogel (Deborah Vogel), Akacje kwitna: Montaze (The Acacias Bloom: Montages).

Bibliography

Bruno Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles (published originally in Polish under the title Sklepy cynamonowe/Cinnamon Shops), translated by Celina Wieniewska, 1977).

Bruno Schulz, Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass (Sanatorium pod klepsydra, translated by Celina Wieniewska, 1978).

Jerzy Ficowski, ed., translated by Walter Arndt with Victoria Nelson, Letters and Drawings of Bruno Schulz with Selected Prose (Harper and Row, 1988).

Jerzy Ficowski, Regions of the Great Heresy: A Biographical Portrait, translated and edited by Theodosia Robertson (Norton, 2003).

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.