Interpretations of Timothy O’Sullivan’s "Ancient Ruins"

Maya Wali Richardson is a student at NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study. This blog post is derived from her work in Shelley Rice’s class "Aesthetic History of Photography."

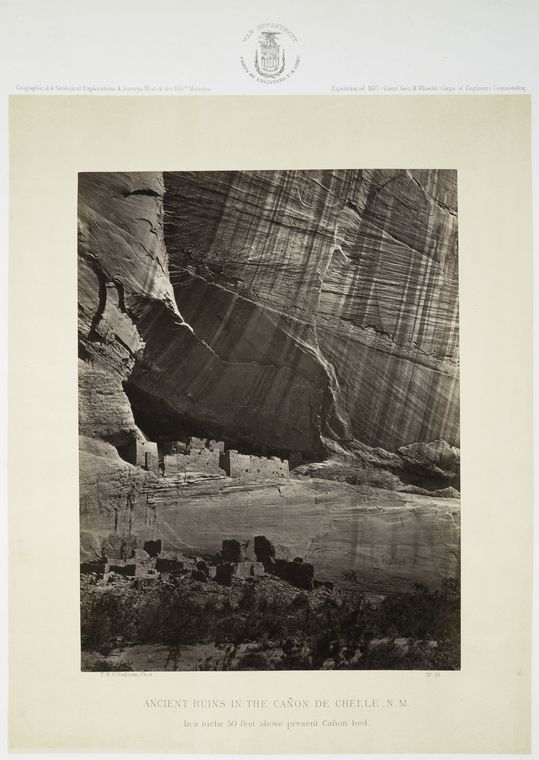

Seen on view in The Public Eye: 175 Years of Sharing and Photography is one of Timothy O’Sullivan’s photographs: Ancient ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, N.M. in a niche 50 feet above present canon bed, from 1873. O’Sullivan was employed as the chief photographer for the Wheeler Survey, a government sponsored organization headed by George Wheeler from 1871 to 1879. The purpose of the survey was to chart the settling of the American West and it conducted topographic and scientific research by mapping and recording information on the terrain and natural resources of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. The incredibly stunning image depicts ancient architectural structures embedded within a cave of a large cliff. The image is often on view in art museums, even though the image was first created for a topographical survey. It is fully embedded with photography’s complex relationship to science and art.

The scientific objective is evident in Ancient Ruins. The perspective the camera takes is head-on with the bottom of the image being parallel to the ground with no tilt upwards, and the sides of the image being parallel to the vertical walls of the structures. This gives the image a methodical impression. The full title of the photograph includes information on the exact location and height of the cavern. In addition, when looked at closely, two figures can be seen standing on one of the structures. The scale of the ruins is experienced through those small human figures, as well as the fact that the cliff side continues on past the frame of the photograph.

In 1937 Beaumont Newhall decided to include Ancient Ruins in his photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It is not hard to understand why Newhall would include the photograph; the tones and contrast of the image that emphasize the sediment layers make the image visually striking and captivating. While the addition of the human figures may function as an informative tool, it also draws attention to the immensity of the natural environment. The architectural structures and the humans seem minuscule in comparison to the power and enormity of the natural rock, and create feelings of vulnerability within the viewer. The tones, contrast, and framing of the image turn the photograph into an abstraction of textures.

In the context of one of the large Wheeler Survey albums, the photograph was merely a part of a collection of maps, sketches, journals, and topographical and meteorological records. The photograph existed as a supplemental instrument to confirm the findings of the report. Though O’Sullivan’s original intentions may have been in a purely topographical realm, the interpretation of the image within the museum sphere reshaped it. Matted, framed and put on the wall of a museum, Ancient Ruins is placed in the realm of art. The focus shifts from the content to its form. In delving into the multiple ways this one photograph can be contextualized and analyzed it becomes evident that while meaning and significance may be inherent, it is not necessarily fixed.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.