Lawmen and Badmen: The Tin Star of the Old West

In the old movies about the Old West, when grizzled, chawing, cussing, murdering highwaymen ride into town and disturb the peace, from behind the batwing doors of the lawman’s office steps the badge-wearing, fast-shooting, strong-silent-type. The banditti are savage and lawless. The lawman is good.

The lawman might be a U.S. marshal, appointed by the Attorney General, under whose loose, vague authority the marshal operated until the Department of Justice was organized in 1870; or he might be a local sheriff, elected to office by the townspeople. Out West, where systems of order were as scarce as systems of plumbing, the marshal and the sheriff assumed the persona of the law. The distinction often makes no difference in old Western movies, but is an optimum detail in the pursuit of genealogy and local history research in the Milstein Division, where reference librarians must wrangle between the local, county, state, and federal levels in order to rope in relevant resources for patron requests.

In Silver Lode (1954), sneer-and-swagger character actor Dan Duryea plays Ned McCarty, who rides into town on the 4th of July brandishing a marshal’s “tin star” and a warrant for the arrest of local rancher Dan Ballard. Turns out McCarty is an impostor, and hellbent to avenge the murder of his brother, whom Ballard shot in self defense; but by the time Ballard is exonerated, McCarty has riled up the whole town against him, and stars-and-stripes morality devolves into mob justice. Silver Lode proves that the badmen weren’t always bad, and the lawman wasn’t always lawful.

The old High German roots of the word marshal, “master of the horse,” befit both the iconography and transit of the frontier lawman. Marshals and sheriffs had the right to deputize civilians and assemble the posse comitatus, which etymology invokes research methods in local history librarianship, the “power of the county.” For example, marriage certificates are issued at the local level in New York City, the county level in Arizona, and the state level in Virginia. Death certificates are sealed for seventy-five years in Oklahoma, but in Connecticut they are public record before 1997. In New Mexico, birth and death certificates are obtained from the state, but marriages from the county clerk. Like military pension files, census schedules and bankruptcy petitions, naturalization records are filed at the federal level, but before 1906 citizenship may also have been applied for at county courts. Deeds and land conveyances are filed at the county level, and likewise probate records, housed in the records room of the Surrogate's Court, which court is a "surrogate” of the governor’s office, dating back to colonial times when travel to the capital was distant, grueling, and slow.

Access to court records, whether historic or last week, will also vary by state. For example, after the grand jury in Ferguson, Missouri decided against the indictment of Officer Darren Wilson in the shooting death of Michael Brown, the St. Louis County prosecutor’s office immediately made public the court documents in the case. However, at the State Supreme Court in Richmond County, New York, where the grand jury proceedings against Officer Pantaleo in the chokehold death of Eric Garner also ended without indictment, court documents related to the case have remained sealed. The release of the documents, in accordance with state laws, was argued before a state judge in Richmond County this past February. In the future, researchers seeking court records related to the case will be directed by local history librarians to the Richmond County Clerk, despite that grand jury proceedings since the 17th century have been kept secret. In addition, any research into the investigation of civil rights violations committed by the Ferguson Police Department would seek documents issued by the Department of Justice, which federal organization also employs the U.S. marshal.

The Milstein Division holds a handful of guidebooks in tracking legal records:

- Court records -- United States -- States -- Directories.

- Court records -- United States.

- Court records -- [NAME OF STATE].

- Court records – [NAME OF STATE] – [NAME OF COUNTY].

And local history materials are best corralled from the catalog at the town or county level:

- Virginia City (Nev.) -- History.

- El Paso (Tex.) -- Description and travel.

- Dona Ana County (N.M.) -- Maps.

- Sebastian County (Ark.) -- Genealogy.

“When General Stephen Watts Kearny inaugurated the American system of justice in the Southwest in 1846, he introduced a judiciary long common to Anglo-American civilization.” Under the entry for “law and order,” The New Encyclopedia of the American West says that “pioneers did not create new forms of law and order; rather they continued to use two ancient English institutions: the justice court, headed by the justice of the peace; and a county, or high, sheriff, with powers to collect taxes, deputize citizens, and form a posse.” The English roots of this system are reflected in the word "sheriff," where a “shire” is the one-thousand year old ancestor of “the modern county in the United States,” and “the principal officer of the shire court was the shire reeve.” Ironically, like the U.S. marshal in Silver Lode, the Sheriff of Nottingham is portrayed as the archvillain in the folklore of the radical and righteous bandit Robin Hood. Director Allan Dwan, who helmed Silver Lode, adapted the Robin Hood tale thirty years earlier, starring Douglas Fairbanks.

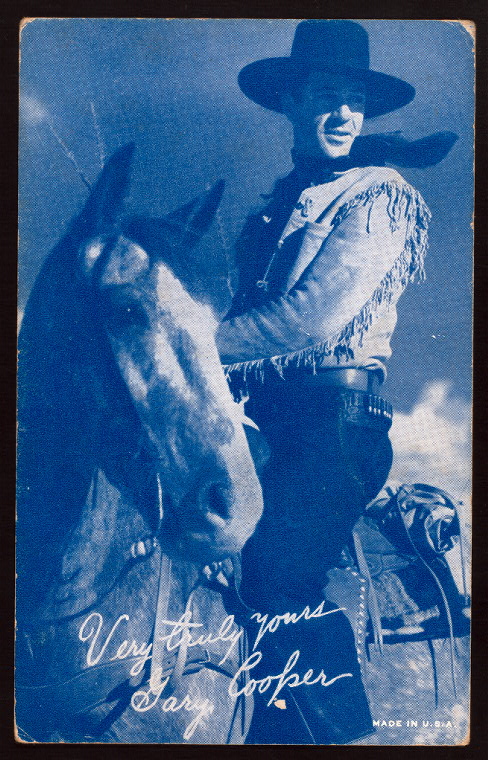

In High Noon (1952) Gary Cooper plays the town marshal, basically the sheriff, though sometimes the nomenclature was scotched, and, like many early genealogical records, the verbiage more pragmatic than official. Bad Ben Miller seeks revenge on the marshal, but the townspeople, who elected the law-bringer by popular vote and attended his wedding, refuse to support him against the brigands.

When Wyatt Earp, his two brothers, and tubercular ex-dentist rifleman Doc Holliday killed Billy Clanton and the McLaury brothers at the O.K. Corral, in Tombstone, Cochise County, Arizona, Earp had been deputized a U.S. marshal. Surely no heroic showdown between the good and the bad, prolific oater-epicist Larry McMurtry described the ugly gunfight as little more than a "botched arrest." Earp was later indicted in Pima County, AZ, for the vendetta killing of Frank Stilwell, whom had back-shot brother Morgan Earp in 1882. With regards to how folks like to remember the old West, it may be a sign that the NYPL catalog shows 28 entries under the subject heading Cochise County (Ariz.) – Fiction, but only 5 for Cochise County (Ariz.) -- History.

Wichita (1955) is a cinematic Wyatt Earp origin story, where the burgeoning Kansas cattle town has plenty of saloons but no medical doctor, and the current marshal is a yellowbelly, which is an advantage when the ruffian cattle drivers swoop into town, drain the supply of whiskey, and start shooting up the place. After a stray bullet kills a young boy, Wyatt Earp takes up the marshal’s badge and gun, jails the sozzled cowpokes, and bans firearms within city limits. These were the powers of the marshal, whether local or federal; and he often did not just run the jail, but sometimes also resided in the building with his family.

From the 1789 Judiciary Act, when the office of U.S. Marshal was established, to roughly the 1850s, when the territory of New Mexico was created, the marshal carried out the modern duties of the post office, FBI, and Secret Service. In the antebellum years the marshal enforced the Fugitive Slave Act and postbellum the Civil Rights Act. He was an agent of the courts, a server of subpoenas and warrants of eviction, an overseer of prisoners, supervisor of elections, collector of taxes, and, for some time, most relevant to the historian of family history, the marshal took the census. The inaugural 1790 census was compiled by 650 federal marshals, who spent 18 months trekking the 13 states and enumerated 3.9 million residents.

Presently, city marshals in the five boroughs are appointed by the Mayor and regulated by the corruption-busting Department of Investigation, but are described as neither employees of the city nor the Civil Court. Like U.S. marshals before 1896, they earn funds by a system of fees. Marshals both east and west collected fees based on court duties and service of process, in what was part of the “entrepreneurial” system of law enforcement, versus the bureaucratic and municipal system codified by the onset of the early 20th century. In addition, central authority west of the Mississippi was dwarfed by the zealous and domineering control of private industry, which also paid for security with greater dispatch than Uncle Sam. As Southern California chronicler Carey McWilliams writes in “Myths of the West,” his debunking 1931 essay, “the cattle companies captured Nevada after 1861; Montana was merely the alter ego of the Anaconda Copper Company until recent years; the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company ruled Colorado during its formative period; while in Idaho and Wyoming the Union Pacific played the villain.”

In the opening courtroom sequences of True Grit, the 2010 adaptation of the 1968 novel, U.S. marshal Rooster Cogburn is accused by an Ozarks counselor of exploiting his federal authority in several questionably justified shootings. Marshal Cogburn is gruff and unapologetic. The local sheriff describes him as mean, pitiless, and “double tough.” But such was the beleaguered bathos of a late 19th century U.S. marshal, that Cogburn lives in the cramped backroom of a Chinese grocery and haggles reward money with a 14 year-old girl out to avenge the murder of her father.

In the old western district of Arkansas, families of slain deputies received no compensation from the government, and marshals received no fees if they failed to capture their fugitive, no matter the travel and time expended, nor were they paid if the fugitive was killed during the act of apprehension. Pulp writers and eyepatch-clad Hollywood directors would stretch the legacy of the entrepreneurial system into the pop mythos of cheroot-smoking bounty hunters, leather-jawed freebooters, and ivory-handled guns-for-hire.

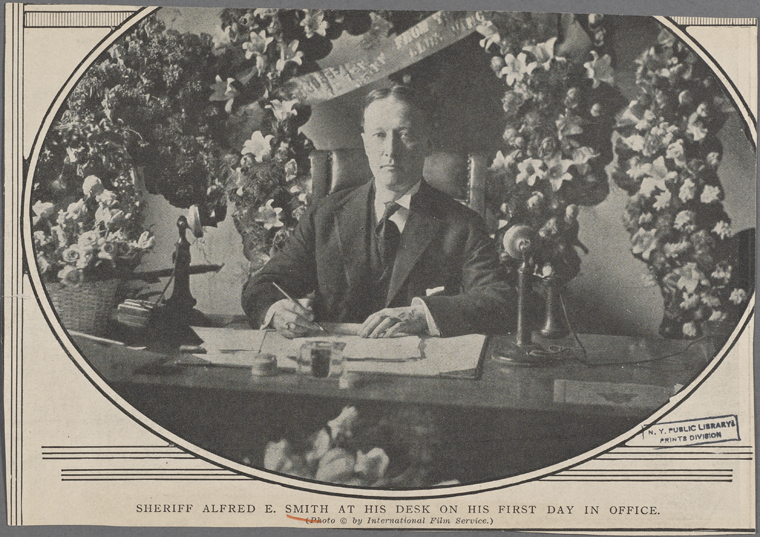

New York City continues to run a Sheriff’s Office, which Alfred E. Smith once occupied as a patronage gift from Tammany Hall at $50,000. a year, in the years prior to Sheriff Smith’s garnering the NY Governorship.

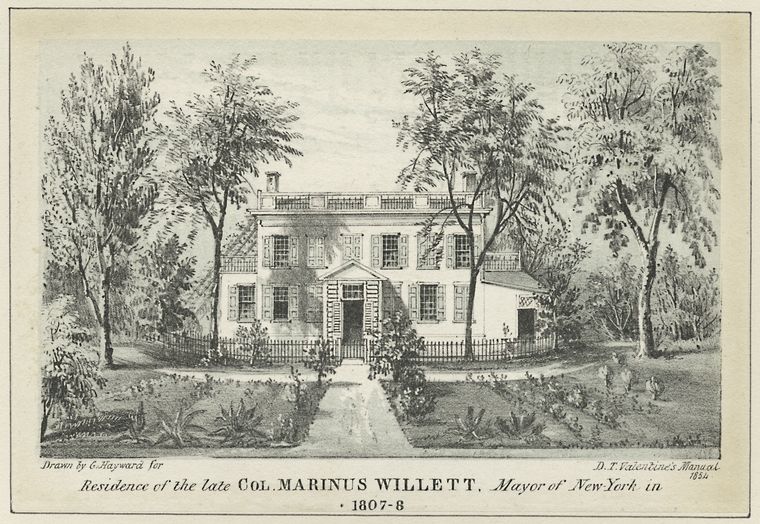

In Manhattan one still finds Sheriff Street, between Houston and Stanton and bisected by the Samuel Gompers Houses to continue one block under the Williamsburg Bridge. The city named Sheriff Street in honor of Marinus Willett, a swashbuckling New York City Tory-fighter who led the Sons of Liberty radicals in sacking the British arsenal in occupied Manhattan, invaded Canada, fought under General Washington at Monmouth, and held the esteemed office of Sheriff of the City and County of New York in 1784-1788 and again in 1792-1796. In between these terms, President Washington sent Willett south to Georgia to treaty with the Creek Nation. The street runs through the old 13th Ward, in the Southeast frontier of the island where Sheriff Willett lived after the war.

Bibliography

Annual Report of the Attorney General of the United States.

Ball, Larry D. “Frontier Sheriffs at Work.” The Journal of Arizona History. Vol. 27, No. 3, Autumn 1986.

Ball, Larry D. “Pioneer Lawman: Crawley P. Dake and Law Enforcement on the Southwestern Frontier.” The Journal of Arizona History. Vol. 14, No. 3, Autumn 1973.

Cooley, Rita W. “The Office of United States Marshal.” The Western Political Quarterly. Vol. 12, No. 1, Mar. 1959.

Dressler, Joshua (ed.) Encyclopedia of Crime and Justice. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2002.

Eichholz, Alice (ed.) Red Book: American state, county, and town sources. Provo, Utah: Ancestry, 2004.

Jordan, P.D. “The Town Marshal Local Arm of the Law.” Arizona and the West. Vol. 16, No. 4, Winter 1974.

Lamar, Howard R. (ed.) The New Encyclopedia of the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Malone, Dumas (ed.) Dictionary of American Biography. Vol XX. NY: Scribner, 1928-1958.

McMurtry, Larry. "Back to the O.K. Corral." New York Review of Books. March 24, 2005.

Sankey, Michael (ed.) BRB's guide to county court records : a national resource to criminal, civil, and probate records found at the nation's county, parish, and municipal courts. BRB Publications, Inc. 2011.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

![[Gunslinger in the church.]](https://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=G98F842_002&t=w)