Archives

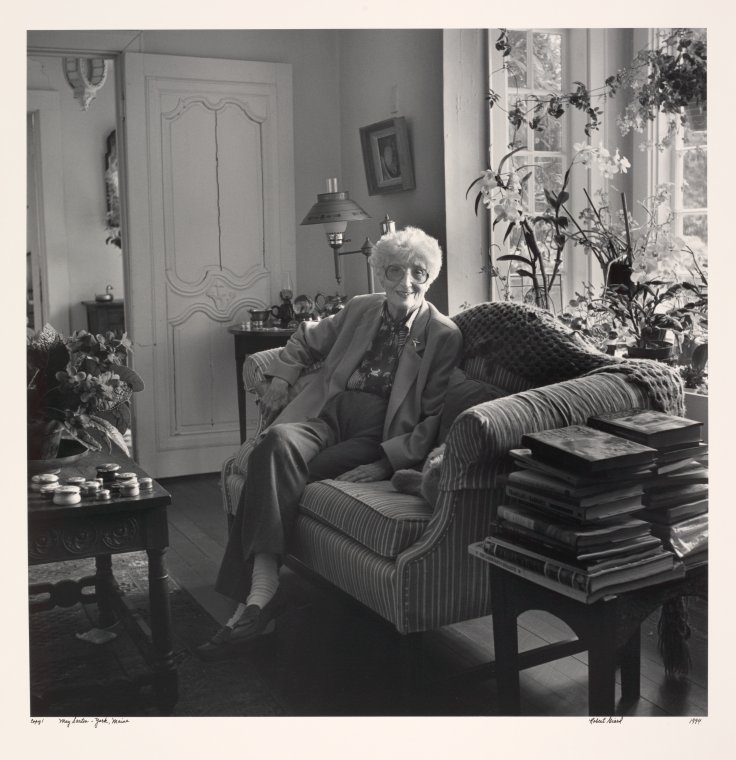

Happy 100th, May Sarton!

May 3rd marks the centenary of the birth of poet and novelist May Sarton. Sarton’s most important novel, Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, tells the story of septuagenarian Hilary Stevens, a poet whose life is retold episodically during an interview with two writers from a literary magazine.

In notes for the draft of Mrs. Stevens, now in the Henry W. and Alfred A. Berg Collection, Sarton cautions herself to "get away from autobiographical in Hilary." Nevertheless, Stevens shares certain superficial characteristics with her creator: both women are poets with a history of romantic relationships with women (Mrs. Stevens was once described as Sarton's "coming out" novel); both avidly garden; both have a habit of mentoring younger, less experienced writers.

More strikingly, Hilary Stevens' attitudes towards writing and feminism, unpacked during her conversations with the interviewers, are echoed in Sarton's letters and journals. Both Sarton and her protagonist in Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing were trenchantly engaged in the problem set of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. How does a woman find the time and space necessary to write successfully? The publication of Mrs. Stevens, a book whose protagonist was both feminist and lesbian, led to an uptick in Sarton's readership at the college level, particularly in Women's Studies courses. Written in 1965, almost 35 years after the publication of Woolf’s long essay, A Room of One's Own hovers like a specter over nearly every page.

One of the most telling moments comes early, as Hilary Stevens rises the morning of the interview:

‘They’ always said, ‘What beautiful flowers you have!’ But ‘they’ never imagined how much time this irrelevant passion took from her work, at least an hour every morning in summer. No man would trouble about such things; the imaginary man in her mind got up at six, never made his bed, did not care a hoot if there were a flower or not, and was at his desk as bright as a button, at dawn, with a whole clear day before him while some woman out of right was making a delicious hot stew for his supper.

Woolf and Sarton met in 1937 at Elizabeth Bowen’s. Soon after they traveled together to Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire. Hermione Lee writes in her biography of Woolf that she found the 25-year-old Sarton “pretty, artificial, and starstruck.” For Sarton, her encounter with Woolf was full of glamour. The writer, who she greatly admired, reminded her of a giraffe, “aristocratic” and “sensitive” (for Woolf, Sarton is only, “that goose.”) In a Berg Collection letter, Woolf teases Sarton, who has written that she finds the thought of Woolf reading her own work scary. Since she’s as “tame as a giraffe," why should she find her intimidating?

Woolf was certainly on Sarton’s mind when she was composing Mrs Stevens. Sarton's notes for the novel contain a reminder to remember Woolf as she’s writing (along with Colette, H.D., Willa Cather, and Sarton’s close friend Louise Bogan). A long list of "phrases Hilary might use," also in the manuscript notes, are inspired by Woolf’s intimate friend and correspondent, Ethel Smyth. And letters exchanged between Woolf and Sarton in the late 1930’s discuss poetry and criticism in language that is reprised in early drafts and the final published novel.

The premise of Sarton’s picaresque novel pivots on her recollections of her encounters with past lovers — "Muses" — who inspire her to write one of her books. For Stevens, each of these meetings is a "collision" of sorts: frequently resulting in a loss of equilibrium, and sometimes serious damage to herself and others. And yet, she is adamant that feeling — even feelings of anger and despair — yield good art. As she tells her interviewers, "eventually her [the Muse's] visitations must be paid for in human terms. And one pays… one is glad to pay."

In a letter in Sarton’s papers, the novelist Madeleine L’Engle writes to Sarton about Mrs. Stevens: "You hit me where I live, you hit beneath the belt… Some of it touched me so deeply that it frightened me…" A decade earlier, Sarton wrote L’Engle a letter on the subject of writing:

…remember that a year or two or even five or ten in the total life of a writer is very short; you are digging deep into reality, the reality of being human, being a mother, having to work a bit too hard etc. and all the time you are accumulating or building up the rich human loam from which books will grow in time. … Sometimes I think (and your crest suggests it) that one of the professional writer’s greatest problems is not to write too much, to keep still… You will be saved from this — and I think it was a danger for you at one time.

Along these lines, Sarton cautions herself in a note in the Berg’s Mrs. Stevens draft to write less, and to cap her daily page count at three.

The Sarton archive is rich in correspondence, and in addition to Bogan, L’Engle and Woolf, includes letters from Elizabeth Bishop, Kay Boyle, Pearl S. Buck, H.D., Eva La Gallienne, Archibald MacLeish, Vera Nabokov, Freya Stark and Jean Tatlock. Sarton’s manuscripts in the Berg also reveal how real the distraction of flowers was for the author, as it was for Hilary. The Berg Collection has eight of Sarton’s garden diaries, including one kept during the years she wrote Mrs. Stevens. The finding aid can be found online.

Sarton will be feted in York, Maine May 3-6 at the May Sarton Centennial Symposium. Register here.

N.b.: Sarton’s draft and notes for Mrs. Stevens live in the Berg Collection not far from the Berg’s intriguing proof copy of Virginia Woolf’s A Room Of One’s Own, acquired in July 2010 and long regarded as lost.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.