All Possible Worlds, Biblio File

Wilbur, the Translator

The travelers are invited to dine at the King's palace. The dinner proceeds merrily, led by their affable royal host:

"Cacambo explained the King's bon-mots to Candide, and notwithstanding they were translated they still appeared to be bon-mots. Of all the things that surprised Candide this was not the least.

Voltaire hits on an especially vexing difficulty of translation here. Translation is by nature imperfect. Even the most skillful translations reveal the incompatibilities between the languages bridged. The writer R .S. Gwynn regards the translator as a diplomat, who must "make the best of a bad compromise between languages", just as nations must account for their myriad cultural differences in acts of negotiation. On the one hand, a translation has the potential to exultantly innovate, to take the essence of a literary work and express it in another key. On the other, translations will always be duplicates--diluted copies of a choate original.

As a translator, Cacambo possesses a rare power. Not only has he proved an effective interpreter, but he's also managed to spin what is clever and witty in one language into what is clever and witty in another. The king's charm and skill in wordplay are no less powerful after translation. In the eyes of Richard Wilbur, lyricist of Bernstein's operetta Candide and a renowned translator himself, this is translation's most desirable effect.

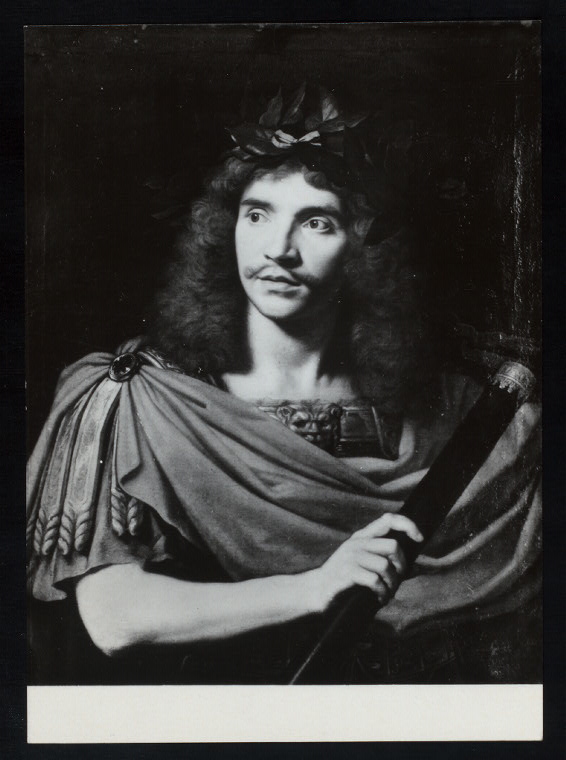

The literary critic Dana Gioia counts Wilbur, along with Longfellow, Pound and Fitzgerald among the four greatest American translators of poetry. Wilbur's reputation as a poet is common knowledge, but his role in reviving seventeenth-century French drama for English-speaking audiences is less well-known. The poet first encountered Moliere's work in 1948, at the Comedie-Francaise (In chapter 22, Candide has his first encounter with Corneille's work here). Seeing Cyrano de Bergerac gave Wilbur the idea that old French plays could be relevant for the American theater. Since 1952, the year he began work on Moliere's Misanthrope, Wilbur has translated half a score more and has added to his belt two plays by Racine and three by Corneille. Corneille's El Cid and The Liar, were just published late last year.

For Wilbur, the English translation is no different. The poet insists that Moliere's alexandrines must be rendered as rhymed pentameter, and not in prose form. Brian Bedford compares the effect of Wilbur's couplets to a ping pong ball afloat on a jet of water, where the couplets buoy the text up and fizz delectably.

Wilbur's approach to translation, detailed in a 1975 interview, is instructive. At times, he uses a gamer's language to describe his process, invoking the importance of "rhyming solutions" and likening the work of translating a Moliere speech to completing one corner of a crossword. To the claim that the Russian poet Yevtushenko once estimated only one or two unused rhymes left in the world, somewhere in Argentina, Wilbur agrees. He argues that creating natural verse is a matter of exercising patience, and of creating rhymes that sound fresh, even if they've been well used. Even so, he refuses to see English as a rhyme-poor language. Wilbur recounts looking at an already-published English verse translation of Moliere's School for Wives after finishing his own, somewhat fearful that he might have unintentionally duplicated the rhymes within. The first two rhymes were the same. After that, the rhymes in the two translations rarely overlapped.

Racine, often characterized as untranslatable, was more challenging. Wilbur admits to finding him harder going, and here, takes the position that a more faithful translation of his work is the most viable. He has emphasized that the translator's role is not to recast Racine as if a contemporary soap opera: In a Fall 1984 issue of The Sewanee Review, Wilbur is quoted as saying,

"Our best hope, I think, is to see whether a maximum fidelity, in text and in performance, might not adapt us to it [author's emphasis]."

Wilbur admits that after completing an 1800 line Moliere play he's been known to spend the next few months thinking in couplets--an intriguing side effect for one already predisposed to creating original verse. He has said in interviews that writing the libretto for Candide did not infect his brain nearly to the extent that translating the seventeenth-century dramatists did. Wilbur translated his first play, The Misanthrope, without attention to how it would sound spoken aloud, but after working with the actors for its maiden production, he revised his process. For his next Moliere project, he began to sound out every line in his head, selecting of all possible iterations the one that an actor could speak most effortlessly. He credits his translation work with making his own poetry more dramatic.

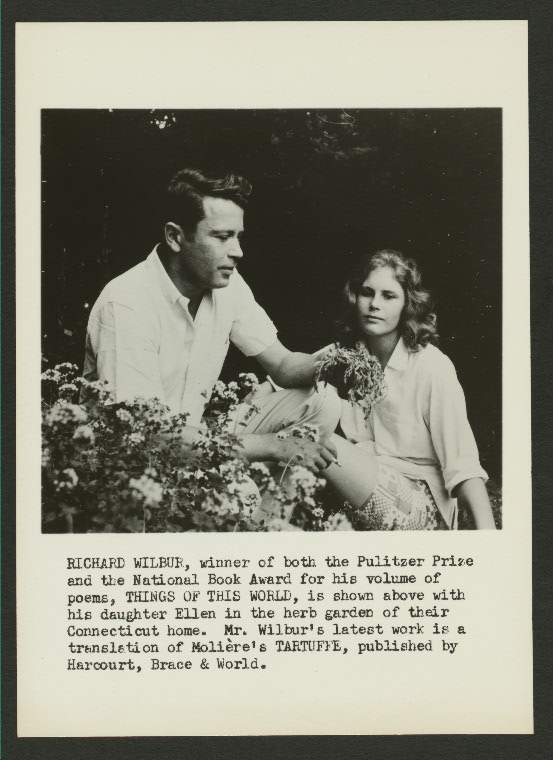

Wilbur has spoken about the responsibilities of the translator--responsibility both to the original text, and to its writer. By his own account, choosing the words doesn't always come easily. One is reminded of "The Writer" at the heart of Wilbur's poem of the same name, a poem in which Wilbur recalls his daughter Ellen in the act of composing:

A stillness greatens, in which

The whole house seems to be thinking,

And then she is at it again with a bunched clamor

Of strokes, and again is silent.

Last year, Wilbur spoke of his own aptitude for the task at hand:

"My chief virtue as a translator is stubbornness: I will spend a whole spring day, a perfect day for tennis, getting one or two lines right."

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.