Feminism's First Wave: Lillian Wald and the Henry Street Settlement

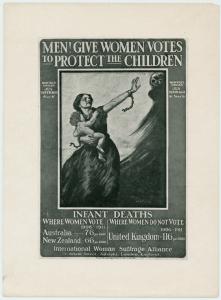

This sentiment, originating during WWI, is an example of the many tools first wave feminists used in their efforts to obtain the right to vote. Women of the first wave argued that the vote would allow them to fix social ills such as poverty, child labor, alcoholism, and the war, and they used these issues as political levers to achieve their suffrage goal. This was not a cynical calculation, however: these early feminists and suffragists believed in their causes and would go far to fight for them. Numerous activists were put on trial, arrested, force-fed, hounded and harassed in the papers for their adherence to the belief that women deserved a political voice, just like any man.

In the U.S., the first wave is generally considered the period from the mid-1800s, with the conference at Seneca Falls, through the installation of universal suffrage in 1920. While the women involved were most often from the privileged class, they understood a fact that is still central to the tenets of the feminist movement today: the condition of women as a whole has a great impact on the well-being of society. Thus, among the feminist causes of the era were pacifism, birth control, temperance(pdf), dress reform, Anarchism, free love, and the improvement of social and economic conditions for immigrants and the poor.

Feminist activists, however, were often divided as to which method was likely to be the most successful towards elevating women, and thus society. Should all efforts first and foremost be dedicated to the suffrage fight, the success of which would naturally flow to other causes? Or was it more important to strike while the iron was hot; while women had the stage, should they should pursue every agenda simultaneously?

Of the women involved in these progressive feminist movements, only a few names are familiar to most Americans. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are commonly recognized, but have you heard of Lillian Wald? (pdf)

The daughter of German immigrants, Lillian Wald founded the Henry Street Settlement house and the Visiting Nurse Service of New York –both of which remain active service organizations in the city today.

Miss Wald began life somewhat comfortably, attending Miss Cruttenden’s English-French Boarding and Day School for Young Ladies and Little Girls. After an application to Vassar was rejected, she happened upon the profession of nursing, moved to New York and enrolled in the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary. Her studies soon exposed her to the poverty and unsanitary conditions of the over-crowded and unregulated tenements of the Lower East Side. Disgusted at the life that inhabitants of the neighborhood were subjected to, in 1895 Wald opened the Henry Street Settlement.

The settlement originally served as a nexus for her Nurses’ Service, which provided New Yorkers with affordable at-home medical care, by visiting nurses. The nurses did everything from caring for the sick and dying, to monitoring mothers’ and newborns’ health, to training older children in the proper care of their younger siblings. In addition to these health services, the Settlement soon broadened into a social service organization offering a playground and activities for children, public lectures, English classes for new immigrants, a theater, and other benefits not otherwise available to the poor. At the same time the Nurses’ Service grew, extending to include nurses in public schools. At the time of Wald’s death in 1940, the Visiting Nurse Service of New York had a staff of nearly 300.

Lillian Wald’s involvement in the lives of disadvantaged New Yorkers led her to advocate for child laborers and the creation of playgrounds around the city, support trade unionism and suffrage rights for women, and become involved in anti-war activism during World War I. Wald, whose feminist beliefs and benevolent service were closely linked, was by no means a “one issue” woman. Like many of her colleagues, she drew links between the lives of women and larger social issues.

While some at the time considered the varying foci of the early feminists to be an indication of the flightiness of females, I would argue Wald was an example of the practical multi-dimensionality of the First Wavers: she worked for the reforms she felt most necessary to improve women’s lives. For many of her cohort, universal suffrage was crucial, not merely for its own sake, but as the tool that would allow women greater influence in the issues so dear to their hearts. To read more about Miss Wald and her work, check out her books The House on Henry Street and Windows on Henry Street.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.